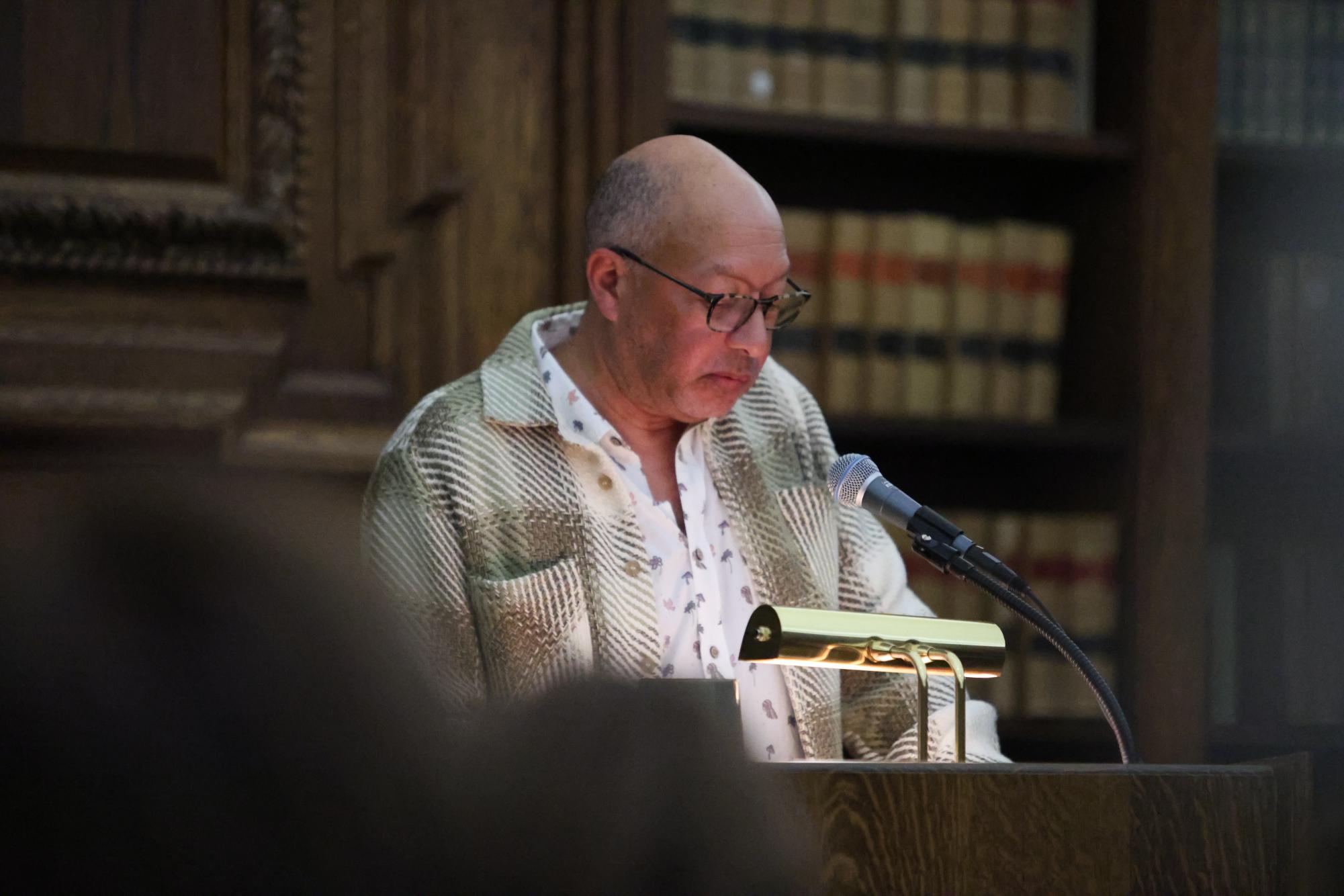

On most nights, the 24-hour room in Sawyer Library is the site of frantic last-minute studying and frazzled tutorial paper-writing. However, last Thursday at 7 p.m., students and faculty gathered there for a far less stressful reason: listening as Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Carl Phillips read some of his latest work. Hosted by the English department, the event was part of the Williams Literary Arts Reading Series.

Phillips is the author of 17 poetry books, the first of which won the Samuel French Morse Poetry Prize in 1992. His poetry has received praise for its textured syntax and nuanced allusions. With an undergraduate degree in Greek and Latin, Phillips often imbues his poems with classical references. At the event, he read from his 2024 collection Scattered Snows, to the North.

Over the course of his career, Phillips has received numerous accolades, including the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the 2021 Jackson Poetry Prize. He has taught poetry at Washington University in St. Louis, Harvard, and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Throughout the reading, Phillips interspersed his poems with simple introductions and deadpan quips. “This title comes from something someone asked me to do,” he said while introducing one poem. “Instead of being mean I decided to just obey them. They said, ‘Could you be more specific when it comes to longing?’ So, this poem is called ‘On Being Asked To Be More Specific When It Comes to Longing.’”

While the reading was a first introduction to Phillips’ poetry for some, others were previously acquainted. “Carl’s poems have been among my go-to’s for 20 years,” poet, editor, and Senior Lecturer in English and American Studies Cassandra Cleghorn wrote in an email to the Record. “I was a classicist in an earlier life, so I’ve always especially loved that substrate of his work. My favorite poem from the night was ‘Something to Believe In,’ which has everything I need in a poem: dogs, the Iliad, and lines like this: ‘Our breathing /ripples the way oblivion does — routinely, across history’s face.’”

“It was a thrill to get to hear him here at home and to see so many folks from the community beyond the College come out for poetry,” she wrote.

Earlier in the day, Phillips joined the “Advanced Workshop in Poetry,” a course taught by Professor of English Jessica Fisher. In conversation with students, Phillips discussed his craft as a poet at greater length. “[Poetry] comes from a very intimate space, and often a space that I myself am not routinely in touch with,” Phillips explained to the class. “I think that’s why writing is like exorcising demons in a way. There’s the way we talk in a café or a classroom or something, but then there’s all the weird, messed-upness of being human, and we’re taught not to talk about that, but a poem seems a safe space to explore those things and to imagine another side of yourself.”

For Phillips, inspiration often emerges gradually from the mundane. “Usually [while] doing something like walking a dog or cooking or something, out of the blue, some line will just come, or a fragment, or a word,” he told the class.

In the class, Phillips said that he spends several weeks compiling his collection of words and phrases before crafting any poems. “I’ll write [words] down in this little notebook and/or on my phone Notes app,” he said. “About once a month, at night, I’ll sit there and think. I have a feeling [that] it might be fun to sort of start pushing a couple [words or fragments] together to see what happens, and with luck, things will just start connecting.”

Although the body of his poems tends to come together over the course of a few nights, Philips’ titles take longer to emerge, he explained. “The hardest thing for me is the title,” he said. “It always comes many days, weeks after the poem’s written, and I think that’s because I don’t always know what I’m writing about for a while.”

Despite his illustrious publishing career, Phillips does not approach his creative process with the intention of completing a collection. “I can only write poem by poem,” he said to the class. “I never write thinking I’m working on a book… I can’t track out a trajectory.”

Sometimes, the anthologies are born from sudden connections between poems, Phillips explained. “I had a poem where someone was pursuing a deer through the woods, and I had another one where a deer was attacking a human as they were fleeing the woods, and that gave me the idea that those would be the first and last poems [in the collection],” he continued. “The idea would be that the very thing you were in pursuit of turns around, and you kind of have to run for your life… So sometimes the poems themselves announce an order.”

For Cy Karlik ’28, a student in the class, hearing about Phillips’ process helped affirm his own poetic development. “This may not really guide my practice as a poet as much as it simply validates it, but it is always helpful to hear someone else’s process,” Karlik wrote to the Record. “We learned that Phillips actually spends very little time at the page [and] is highly intuitive as a writer. He also mentioned that he rarely understands what he has written after he has written it, a feeling (and often an anxiety) that I imagine most writers have.”

“Of course, one should never copy another’s process, but hearing someone like Phillips talk (being very self-aware of his own peculiarity) makes one less anxious about their own,” he continued.

According to Phillips, the life of a published poet spans the extremes of the personal and the public. “You have to have this combination of arrogance and humility,” he said. “You have to be arrogant enough to think that people not only should read [your work, but] you know their life will be bereft if they don’t read your poems. And you have to believe that. But on the other hand, you have to know that not everything you say is worth hearing.”

Before his tenure as a professor of poetry at Washington University, Phillips taught high school Latin. Now, well into his career, he still finds inspiration from ancient works. “The Iliad is a very influential thing in my life,” he said. “The poems of Sappho were a big reason why I majored in Greek and Latin. I’d never read poems that were so intimate and private, and then to realize they were by this person from the sixth century B.C. seemed wild.”

“I think things that influence us aren’t always apparent in our own poems,” he continued. “But they inform our thinking.”

According to Karlik, inviting artists such as Phillips to the College allows younger artists to find inspiration. “I would urge Williams to make these kinds of events a priority,” he wrote. “Obviously, a name as large as Phillips’ is not necessary at all… It is, however, very nice to be in community with other lovers of poetry.”