Grade inflation continues rise through fall semester, some professors say

February 17, 2021

Though hybrid learning in the fall brought along academic challenges like no other semester, it was also accompanied by students at the College seemingly earning higher grades on average, some professors say.

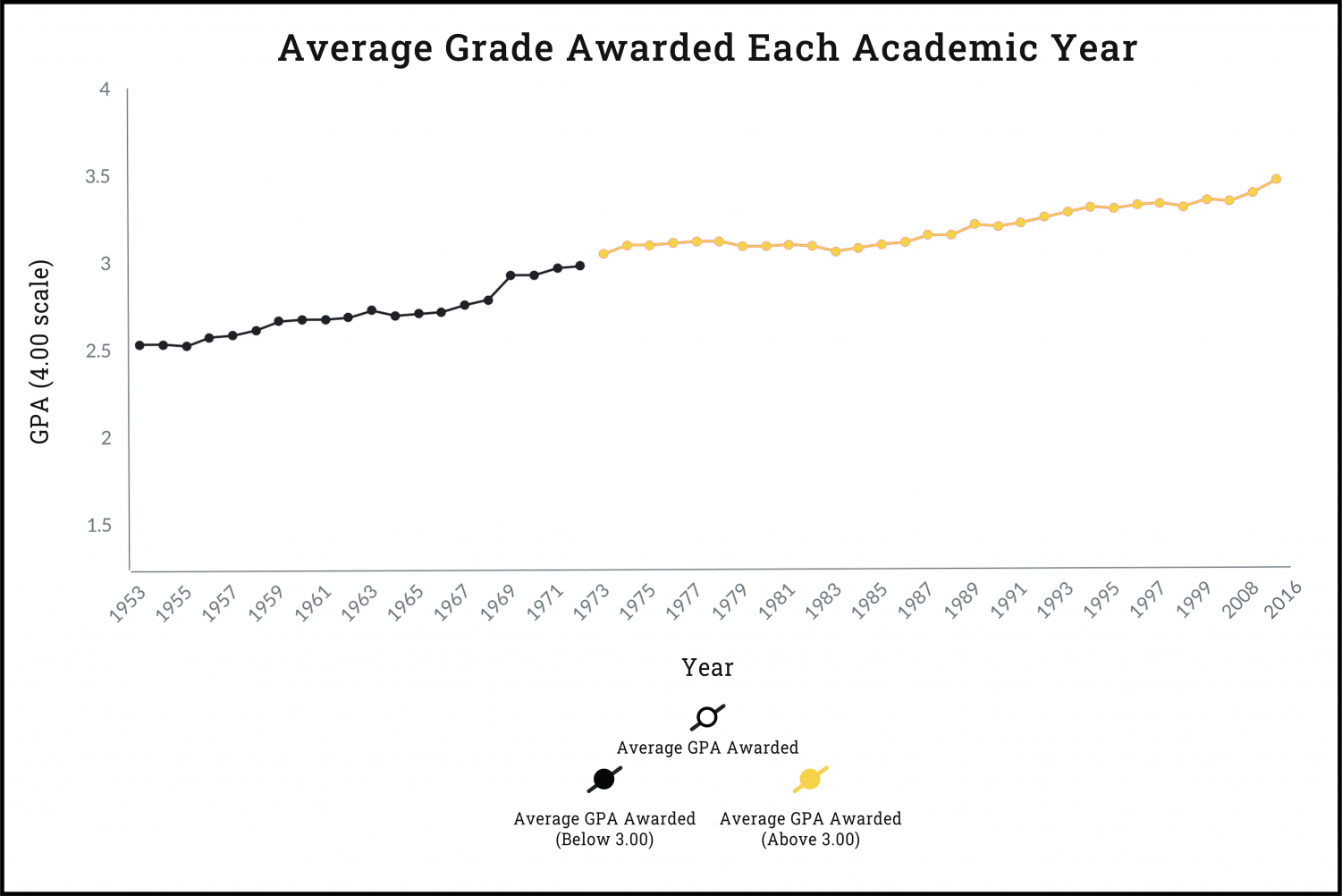

If true, this rise in grades would continue a longstanding trend of grade averages creeping higher each year. Grade inflation has long been present at the College, as well as at other institutions of higher education. For decades, grade averages have steadily risen in all departments at the College. The average grade in 2000 for a class at the College was 3.33; by 2019, it had risen to 3.52, according to a Registrar’s Office document obtained by the Record.

In the fall semester, some faculty felt the pandemic had caused additional grade inflation. “My sense is that grades were significantly higher in the fall than normal,” Professor of Political Science James McAllister said. “But that impression is based on very limited data and conversations with a small number of colleagues.”

Chair and Professor of Political Science Mark Reinhardt agreed. “My grades were actually higher than usual,” he said.

He added that though he didn’t consciously set out to grade students more leniently, he tried to be more understanding of the pandemic’s effect on students. “I tend to be inclined to be super flexible when students are experiencing challenges or difficulties anyway, but I feel that I just ramped that up more this year,” he said.

Other faculty, including Chair and Professor of History Anne Reinhardt were more skeptical that grade inflation had continued in the fall, attributing higher grades to students facing a number of challenges in COVID-era learning, including technical difficulties, health issues, and learning remotely from locations around the world.

“The entire faculty was asked by the administration … to be flexible and to recognize that students were going to have a really wide variety of experiences,” Anne Reinhardt said. She noted that she would not call these occurrences “grade inflation” so much as an acknowledgement of the obstacles students have faced. “If a student has a concern or needs to turn that paper in a few days late than they would normally, then we would say ‘yeah,’” she said.

“I actually would be suspicious of a claim that there’s additional grade inflation this semester,” Anne Reinhardt added.

Without grade distribution data from the fall, it is difficult to be certain whether overall grade averages actually increased. The College declined the Record’s request for last semester’s data. In an email to the Record, Chief Communications Officer Jim Reische said it would be impossible to compare last semester’s data with previous semesters due to all the academic changes, including allowing students to take more classes pass/fail and requiring a minimum of only three courses per semester. “We’re not providing those data because there’s no indication that the proposed analysis would be valid, and in fact are likely to be misleading,” he said.

Mark Reinhardt also pointed to the pass/fail policy as a factor that may have impacted fall grades. In light of unusual circumstances caused by the pandemic, the College changed its policy to allow students to pass/fail as many of their courses as they’d like and still use those courses to fulfill divisional requirements.

Mark Reinhardt said he made his course last semester pass/fail optional so that those who were struggling due to pandemic-related circumstances would not have their GPAs suffer, but instead students with “perfectly respectable” grades chose to take the course pass/fail to improve their GPA. “So whatever the average grade is for the fall would be a skewed representation of how [professors] graded,” he said.

Chair and Professor of Mathematics Mihai Stoiciu said that the rise in grade averages could also be attributed to students at the College putting extraordinary time and effort into their work. “I was deeply moved and impressed by the quality of the work that the students put in in these challenging times,” he said. “The overwhelming majority of students rose to the occasion in a really impressive way. They embraced these new methods of teaching, and they put in their best work. So I wouldn’t be surprised if the grades last semester were higher than in the previous semester.”

Past attempts to reverse grade inflation

The Committee on Educational Affairs (CEA) has sought to rein in grade inflation in the past, albeit somewhat unsuccessfully. Though the practice has not continued in recent semesters, in previous years the CEA would send a memo to faculty each semester reminding them of guidelines for where grade averages should fall, guidelines which had been approved by the faculty in 2000.

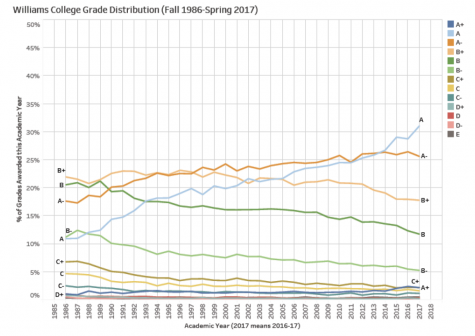

In an April 2018 memo obtained by the Record, the CEA drew attention to the fact that over half of grades awarded were an A- or higher and asked professors to be more stringent in awarding A’s. “Please weigh the decision to give grades at the highest end of the grading scale as carefully as you do the decision to give grades at the lowest end,” the memo said. “The College’s academic policies define an A as ‘excellent,’ and we urge you to reserve that grade for true excellence.”

The memo advised that professors keep the average grade at a 3.2 for a 100-level course and a 3.3 for a 200-level, continuing up to a 3.5 for a 400-level.

These measures to counteract grade inflation did not yield concrete results in practice, according to some professors. For a 100-level course to be at a 3.2, the average would be between a B and a B+. “I doubt that very many courses at Williams come anywhere close to a grade average of a B and a B+,” McAllister said.

Chair and Professor of History Anne Reinhardt said students at the College simply produce high-quality work, and those who put in “slightly less effort” than their peers shouldn’t be penalized with significantly lower grades. “One thing that I wouldn’t want to do in my own classes is to look at some target saying at least 50 percent of students should be getting a B+ or lower and then scale things to that level,” she said. “I’d much rather look at the work the students are producing.”

In the end, the 2018 memo was unsuccessful at reducing grade inflation. “The actual mean grades have been well above those target levels for at least the last decade,” McAllister said. According to a document from the Office of the Registrar obtained by the Record, in the 2018-2019 school year — the most recent academic year unaffected by COVID-19 — the average grade for a 100-level course was 3.44, 3.51 for a 200-level, 3.60 for a 300-level, and 3.68 for a 400-level.

CEA Chair and Professor of History Roger Kittleson said that grade inflation was not a major topic for the committee this year. “We just have other, more pressing matters during the pandemic,” he wrote in an email to the Record.