Entering the main stage of the ’62 Center Thursday evening, one might have initially been struck by the classical Indian music and lament filling the room, performed by vocalist Aditya Prakash and percussionist B C Manjunath. As audience members took their seats, they slowly took in the set design: a lavish living room with ornate cushions and a jhoola (an Indian swing). The set had some unsettling elements as well, such as a menacing ramp in the back with looped ropes hanging down its side, and those in the audience paying particular attention may have noticed the sporadic flickering of the lights and static disrupting the music. So began Akram Khan’s solo work XENOS.

Khan, an English dancer of Bangladeshi descent, is one of Britain’s most celebrated contemporary dancers and choreographers. XENOS is Khan’s depiction of a colonial soldier’s shell-shocked dream during World War I (WWI); it has been attracting high praise and five-star reviews since premiering in Athens in 2017. “This [fictional] soldier was a hugely respected Kathak dancer [a 500-year-old Indian form, which uses elaborate hand gestures and footwork to tell stories],” Khan told The New York Times, “and suddenly his memories and his sense of home are pulled away by the call of the British empire.”

In Greek, “xenos” means stranger or foreigner; in giving the performance this name, Khan sought to honor the stories of the more than one million Indian soldiers enlisted by the British in WWI – mostly peasant-warriors from North and North-Western India – who fought and died in Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Having grown up in London with Bangladeshi parents (where his father owned an Indian restaurant), Khan felt that these narratives were absent in his education.

XENOS also finds inspiration in the Greek myth of Prometheus, who defied the gods to gift fire to humanity and, in doing so, provided the means to its own destruction. One particularly vivid moment from the opening performance includes the set going dark and Khan’s face being lit up by the light of a single match.

The production begins at a wedding celebration of sorts; Khan dances alongside Manjunath’s konnakol (the art of reciting Carnatic percussion syllables), his movements combining contemporary dance and classical kathak. Dressed in a white kurta pajama, with ghungroo (dancing bells) tied to his ankles, Khan intersperses his elegant spinning and stomping with moments of stumbling and falling, giving the audience a glimpse of the uncertainty and disarray to come.

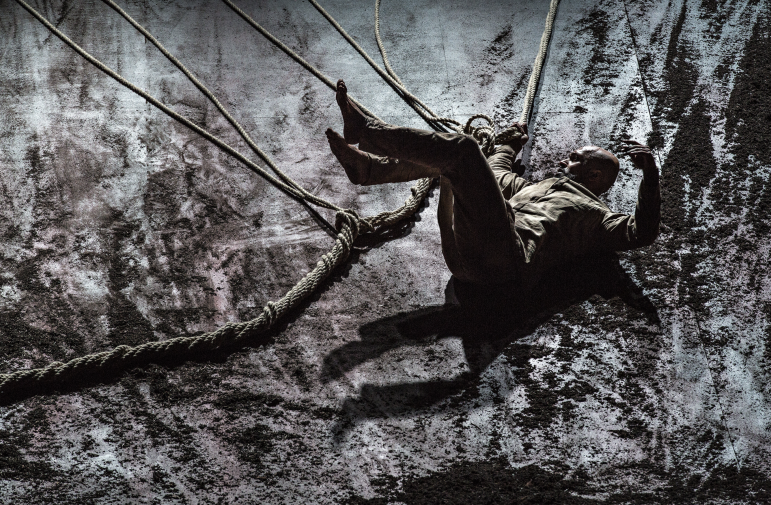

It is perhaps playwright Jordan Tannahill’s sparing script – including the powerful line “this is not war, it is the ending of the world” – and set designer Mirella Weingarten’s dystopian landscapes that give this performance its staggering, unrelenting intensity. When Khan unwraps his ankle bells – holding a strand in each hand – one cannot help but feel unnerved, realizing that they resemble chains. One feels a similar shock when the living room furniture begins to be pulled up a slope at the back of the stage by ropes, leaving Khan alone on a barren stage. The beats of the music merge with gunshots, forming a cacophony which grows louder and louder. Only when it becomes almost unbearable do we realize that the five musicians are floating above the stage in an eerie ensemble of ghosts.

Throughout the performance, Khan remains in motion – the effort visible in the sweat beading on his body – although his costume does change from Indian dress, to military attire to ultimately his bare chest. Indeed, one may assume from the energy of the show that the 44-year-old decided to make this be his final solo show purely because of the physical demands on his body. Yet his age in fact is not his only reason. “The physical shift is a hassle, but it’s the psychological shift that is much greater,” Khan said in an interview with The Economist. “Funnily enough, when I’m on stage I feel I’ve never been so confident, but off-stage I feel terrified…It’s really the fear of messing up or disappointing myself.”

XENOS continues to unfold on this bleak landscape, save for one moment of humor: Khan, holding a rope, finds a gramophone attached to another rope – he is startled to find that tying the two ropes together elicits a recording from the record player. The scene takes a darker turn, however, when the gramophone begins listing out various Indian names, assumedly sepoys, declaring them all dead. The audience watches in horror as Khan frantically struggles to untie the knot.

XENOS cycles through a series of potential endings, before finally concluding dramatically with Khan tumbling down the slanted stage, pinecones cascading around him. Although perhaps Khan was aiming for the melodramatic, I personally felt that a much more poignant ending would have been an earlier scene where the stage turns completely dark, save for the gramophone-turned-lighthouse, scanning the audience left and right.

“The aesthetic is shell-shock,” Khan said in conversation with the Times. “The dance is not just within the body. The body is what communicates, but the body is broken.” Overall, XENOS is a powerful, vehement and at times upsetting testament to those Indian soldiers who’ve gone so long unknown, a preservation of affect which goes beyond the corporeal.