This exhibit, which opened on June 29th, has evoked many mixed feelings regarding Jacob’s Pillow’s use of ethnic garb as costume.

This summer, I interned with the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA), and was told that one of the summer’s highlights would be Dance We Must, an exhibition in collaboration with Berkshire County-based dance troupe Jacob’s Pillow. I was instructed by my supervisor to familiarize myself with the show and familiarize myself I did. No words could ever describe what met my eyes after I trudged upstairs.

Two dimly lit galleries stood before me, each filled with costumes that hailed from various cultures and traditions. Initially awed by the costumes’ beauty and excellent preservation – some of them were over a century old – I was caught off guard by the exhibits’ accompanying text.

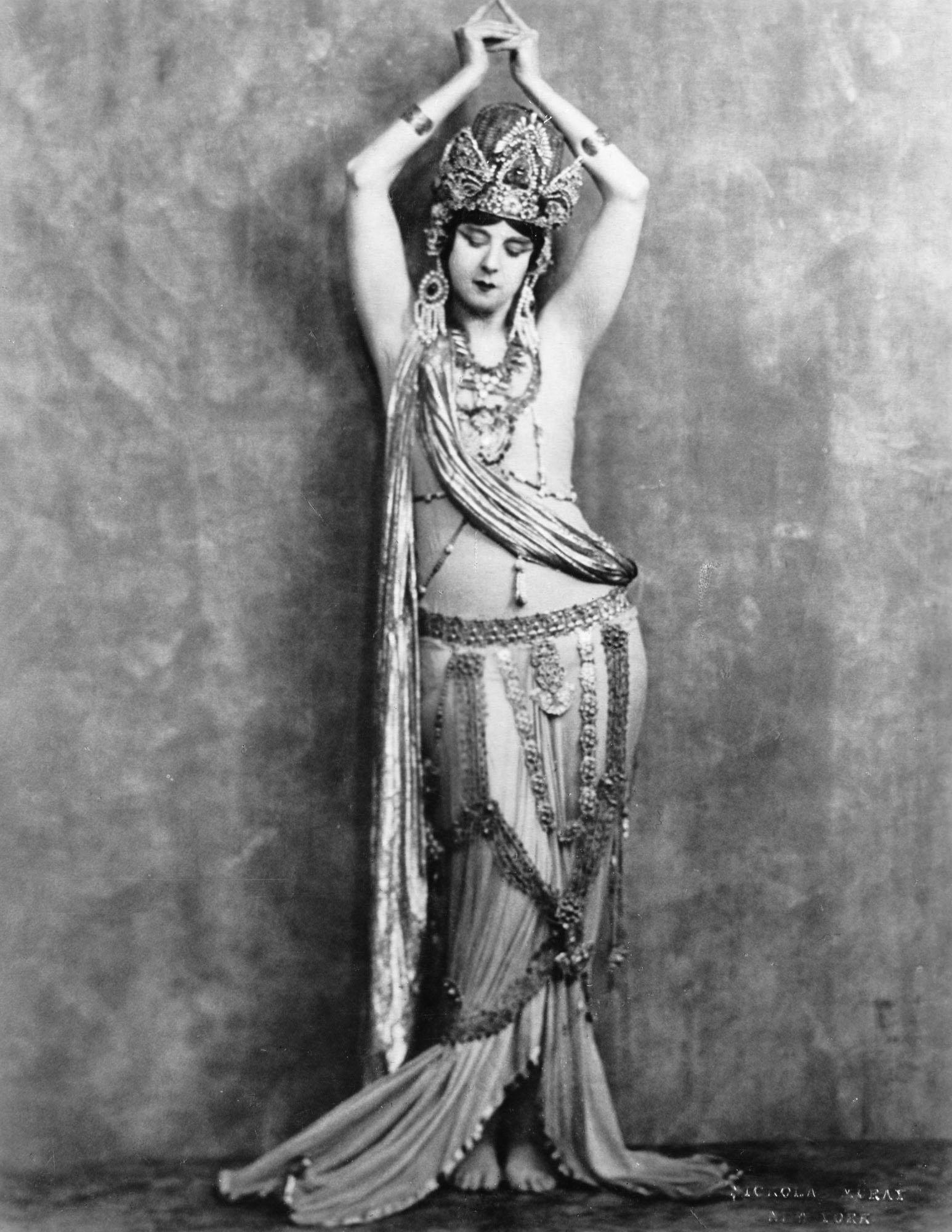

As I circled both spaces, I became increasingly uncomfortable with each plaque I read. The costumes turned out to be created and worn by all-white American dancers performing mostly for American audiences with little to no intention of acknowledging the achievements and complexities of the cultures they attempted to represent; one of the performance sets was named Primitive Rhythms.

Most disconcertingly, a “must-see” piece, a costume made by Ruth St. Denis, supposedly portrays Kuan Yin, a Chinese goddess of mercy who arrived with the spread of Buddhism from South Asia. Whatever St. Denis was trying to embody in her near-sacrilegious ensemble, however, was nothing like the dignified bodhisattva I had so often seen. To see a goddess turned into little more than a striptease character was not in my job description. By the time I walked out of the galleries and into the museum offices, I was unsure of how to go about my work day without breaking down.

In the museum, we called object labels “tombstones.” That term seemed especially appropriate as I contemplated this affront to a deity so closely tied to my culture and to devotees in East Asia, Southeast Asia and the global diaspora.

My fury comes in two parts. Firstly, it is directed at St. Denis and Shawn, the couple who founded Jacob’s Pillow, and at all the performances they have created by twisting elements of my culture and many others’ to fit their ulterior motives. More insultingly, a tombstone next to “Egyptian” costumes explained that St. Denis had debuted with ancient Egyptian-inspired costumes and dances before a new movement directed the vogue towards the greatly colonized Orient and its various religions. Ever opportunistic, she then devoted her creativity (or lack thereof) to aping Asian cultures, while branching out towards Native American mysticism.

Alas, St. Denis and Shawn are dead, but their possessions live on and therefore their deeds continue to haunt us.

The second part is directed at those responsible for the exhibition’s creation and narration. As part of the College, any language in the show would automatically be WCMA-endorsed and, by extension, endorsed by the College. The tombstone next to the “Kuan Yin” costume praised St. Denis for being a “magpie” because she had fashioned it out of literal trash. In another, the couple’s “ingenuity” was again praised for making a “Thai” headdress out of a colander. Although terminology such as ‘cultural appropriation’ and ‘racism’ was peppered throughout the museum text, it felt more like an attempt to utilize buzzwords and give the appearance of addressing the problematic aspects of the exhibits.

With each day that I interned, I encountered countless tourists who marveled at the sheer magnificence of the costumes; completely (perhaps willfully) unaware of the fact that each and every artifact was drenched in the figurative blood of civilizations from whom St. Denis and Shawn had “taken inspiration.” Besides the odd academic expressing concern and/or displeasure at the exhibition – a lady claiming to work for the Museum of Modern Art in New York City told my colleague that it was a disgrace that an institution of the College’s standing should be hosting such an exhibition – the vast majority of our visitors found no fault with the show. This was perhaps the more complicated frustration of the two, but it is the one against which we could still take remedial action. As the show stays open until November, I have proposed alterations or supplements to existing signage to provide an opportunity to talk back.

In an all-staff meeting surrounding the exhibition, an intern argued that the exhibition was celebrating the discovery of century-old archival costumes and materials that formed the building blocks for modern American dance. I countered that this exhibition should therefore be a reckoning that this almost-legendary couple in the world of dance had built the foundations of modern American dance on the appropriation, othering and exoticizing of peoples around the world they deemed “primitive” as much as they had found their cultural practices ‘beautiful’ and ‘spiritual’. This exhibition was a literal showcase of Jacob’s Pillow’s dirty laundry, and an excellent opportunity to educate visitors on histories and narratives they would rather ignore.

As I sat through the strains of piano to which a dance emulating the Maori haka was set, I could only wish I had told every person who had come through WCMA’s glass doors asking specifically to see Dance We Must about all the things that made me uncomfortable in the space. I must say that I hold nothing but respect for the exhibition and its curators, and I still appreciate the beauty of the tainted artifacts. In the meantime, I can only implore you to visit Dance We Must for yourselves and join an all-campus conversation about cultural (mis)appropriation on Sept. 20.