At a predominantly liberal institution, conservative faculty are in the minority

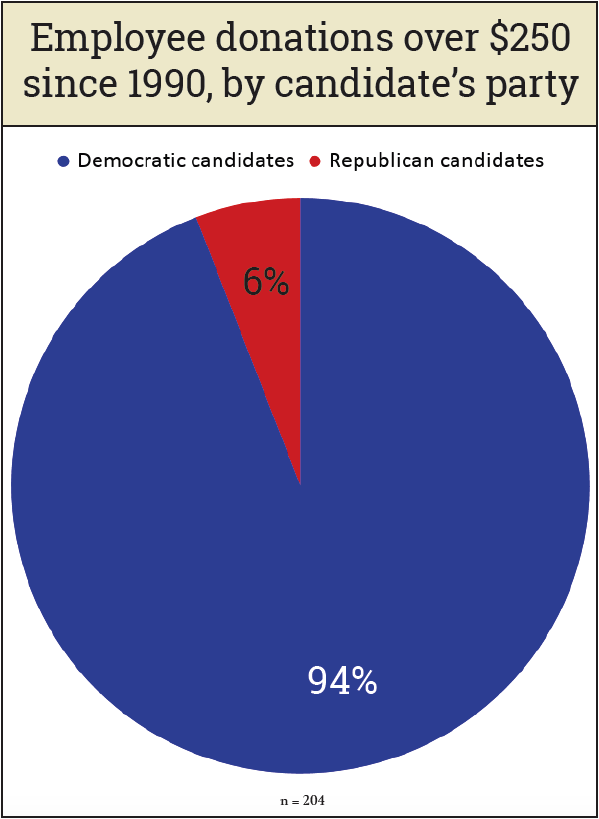

In 2016, the precinct containing the College supported Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump by a margin of 87 percent to 8 percent. This result was far from aberrational — Williamstown and Berkshire County have, since 1984, consistently supported Democrats for president. The College faculty largely matches this demographic, with the vast majority of faculty political donations going to Democratic candidates or committees.

Several professors at the College, however, openly profess conservative views. Their presences in Williamstown have the potential to elucidate political dynamics at the College that may be invisible to the student body’s liberal majority.

Four professors agreed to go on the record for this article: Professor of Mathematics Steven Miller; Professor of Art Michael Lewis; Professor of Political Science Darel Paul; and Visiting Professor of American Foreign Policy Chris Gibson, who will depart the College and begin teaching at Siena College, his alma mater, at the end of the academic year.

While they all fit under the umbrella term of “conservative,” these professors hold a range of beliefs.

Gibson, a former congressman from New York’s 19th congressional district, described himself as a “founding principles conservative” whose beliefs developed during Ronald Reagan’s 1980 candidacy.

Miller called himself a “conservative libertarian” who agrees with portions of Ayn Rand’s objectivism.

Lewis, who spent much of his life as a Democrat, said, “I consider myself a cultural conservative forced by unfortunate circumstances to vote Republican.”

Paul is also a former Democrat, now “a cultural conservative and an economic liberal.”

“I would prefer to leave the politics aside”

These professors sometimes find their beliefs at odds with their students,’ but more often try to avoid interjecting their belief systems into the classroom. “I try not to express ‘my views’ as such, except to say where I find arguments strong or weak, convincing or not,” Paul said. He said he sees his academic mission as convincing students to consider views outside their own, whether or not they align with his.

“I recognize that some students are afraid to speak up and challenge prevailing sentiments, especially on social or cultural issues,” he said. “Therefore, I try to cultivate polite disagreement in class to show that a range of views have logic and evidence on their side.”

When Gibson was asked whether his views might ever cause discomfort for students, he responded, “Well, I hope not. I can never know for sure… I’m trying to be as careful as I can not to give my own viewpoint.”

For Lewis and Miller, who do not teach political science, their personal beliefs are even less likely to emerge in a classroom setting.

“For the most part, I’m fortunate in that it doesn’t really come up often in a math class,” Miller said. “The greatest compliments I ever get from some of the students is when they tell me, ‘Yeah, it wasn’t until two months into the semester when I found out what my professor believed in.’” Miller said he worries that, if students disagree with his views, they may misguidedly fear academic or professional reprisal. Nevertheless, political discussions do sometimes emerge in class: Miller occasionally lectures on the Laffer Curve, which posits that burdensome taxation will reduce revenues, or discusses the 2016 election from an operations-research perspective.

Lewis similarly noted that his art history courses are rarely overtly political, given the subject matter, but said that his ideology can impact his teaching in subtler ways.

“I suppose a person might say that my method of historical narrative is implicitly conservative, predicated on describing the big shape of events and the major factors that make up historical development,” he said. “There is a great reluctance now, in the humanities, to do narrative history. There’s a built-in suspicion of anything that seems to imply certainty.”

Lewis takes pride in the fact that students often cannot detect his ideology. “One of my blue sheets — I will quote it literally — said, ‘I like Professor Lewis’ lectures, although he constantly injects his liberal beliefs into class.’ Actually, I took that as a compliment because I would prefer to leave the politics aside,” he said. His goal, he said, is to give all students a respectful and open-minded hearing in class.

“I feel that a lot of the anger and tension which is in the air is a problem of lack of presumption of goodwill,” he said. “If you come to people with goodwill … people are not going to be walking around with chips on their shoulders and trigger feelings ready to explode.”

Miller added that the need for students to defend their beliefs has been beneficial for at least some conservatives. “I was talking with a colleague who said that one of his students has become a conservative voice, and he credits his time at Williams,” Miller said. “He had to defend his ideas night and day, and he had to become eloquent; he had to become well versed in the facts. He couldn’t be lazy.”

Miller views the ability to speak up and debate as one of the main advantages of tenure. Tenured professors are, he said, “a group of people who have the ability to speak up and be pains in the asses without fear of reprisal… You can always make someone’s life a little bit uncomfortable, but I’m fortunate in that I’m in a pretty safe position.”

“People never hear a rational articulation of a conservative position”

Each professor decried a nationwide culture of polarization that prevents discussions across political difference from occurring. This division can manifest in dehumanizing language toward political opponents, Gibson argued. “Conservatives call progressives evil incarnate. Progressives call conservatives evil incarnate,” he said.

For Lewis, the physical and social division of people with political differences is in part responsible for these changes. “50 years ago, when there was a draft, when you were put in barracks, people from all over America and all over the political spectrum lived together,” he said. “It was happier in that there was more of a country that was one thing, rather than this oil-and-vinegar separation.” He believes that these changes have trickled down to the College itself. “What we’re looking at, I think, is not a sick college,” he said. “You’re looking at a college which honestly reflects serious and distressing developments in our American public life.”

In 1993, when Lewis arrived at the College, he was surprised at how apolitical it was.

“Instead of staying up until dawn worrying about the historical role of the United States, Williams students got a good night’s sleep after going to the gym,” he said. He noticed, however, a shift after approximately 2000. Now, he says, progressivism is “the water we swim in and the air we breathe here.”

Paul, who has taught at the College since 2001, said that the campus culture always had a “liberal bent,” but that this sentiment has grown in recent years.

Miller described student activism as cyclical, but concurred that recent discourse has been less amicable. He said he was disappointed that College Council denied the Williams Initiative for Israel registered student organization status and saw the decision as evidence of a culture that shuts down disagreeable speech.

He also took issue with the 2016 disinvitation of John Derbyshire for the commentator’s racist beliefs. “I believe Derbyshire was going to talk about candidate Trump’s immigration policy, which would’ve been an interesting issue for the campus to hear,” he said.

“The problem of Williams being progressive is this: As the campus approaches, at infinity, absolute progressivism, an unintended consequence is that people never hear a rational articulation of a conservative position but rather hear the worst possible gloss on it from a progressive,” Lewis said. He argued that students who are not used to hearing conservative views will be angered when they do hear them.

A progressive campus, Lewis said, encourages like-minded professors to apply.

“I can sense that with retirements and new hires, most departments are pretty much all progressive,” he said. “There’s a feedback loop: If everyone’s a progressive and you’re making a hiring decision, and someone seems, in the slightest, vaguely, not like you, alarm bells will ring that you are not even aware are being rung.”

“I’ve felt very welcomed on this campus”

Considering the liberal campus environment, professors have often found common cause with conservative students seeking mentorship. “Certain names from the faculty are almost passed down from student to student, as ‘This could be someone you could talk to,’” Miller said.

He added that he welcomes conversations with students of all political persuasions but that conservative students sometimes need like-minded voices. “I think it would be absolutely terrible if conservative students only talked to conservatives, or if liberal students only talked to liberals. But every now and then, it is nice to talk to some people, especially if you’re in a situation where you will be ostracized on this campus if you show happiness that Trump won,” he said.

Gibson and Paul have been more formally involved in conservative student groups on campus. Gibson recalled attending events with the Society for Conservative Thought, including helping to lead a discussion of Patrick Deneen’s book Why Liberalism Failed.

Paul has been heavily involved with the Society for Conservative Thought, as well as with Williams Catholic.

“I would say my main role has been to provide moral and intellectual support,” he said. He also helped lead the discussion on Why Liberalism Failed, and focused his efforts toward providing a nuanced alternative to prevailing campus sentiment.

“Even those who disagreed with [the book] got to see conservatism as an intellectual project rather than as simply a political or, even worse, a narrowly electoral one,” he said.

Most of the professors have found that their beliefs have not proven an impediment to forming strong bonds with fellow faculty. “I’ve felt very welcomed on this campus from both the student body and the faculty,” Gibson said.

Lewis added that the ability to express his viewpoints is an important component of relating to his peers.

“The thing about being a conservative at a progressive college is you have two choices: You live a life of secrecy and fear, or you cheerfully decide that you’re willing to be a pariah if necessary,” he said. “I don’t think you’re a completely realized human being if you’re not willing to be the only person in a room who holds a view that the 19 other people in the room vehemently disagree with.”

Some professors added, however, that the faculty body may not be as monolithically progressive as students may assume. Miller described initiating cautious political conversations with faculty to attempt to gauge their beliefs. “You might start off with saying, ‘I think Beto [O’Rourke] was a little extreme when he said that we should tear down walls that are already built,’ just as a little feeler as to how someone might view political issues,” he said.

Gibson concurred. “Some of my colleagues in the political science faculty actually fall on that [conservative] spectrum,” he said. “While they may not be Trump supporters, they may have some views that do comport with some of the definitions of conservatism.”

For Gibson, however, even if there were ideological friction with his peers, it would be something to which he is accustomed. “This reminds me of when I was a representative,” he said. “One time, I had a constituent who said, ‘What’s it like to be in Congress? You’ve got to debate all those progressives.’ And I said, ‘Are you kidding me? I went to Cornell! At least now I’m getting paid for it.’”