“This Week in Williams History” is a column that looks back at memorable moments in the College’s past through articles in the Record. This week in history, the Record covered the College’s rules for incoming first-years, controversies and protests during Convocation, and first-year traditions.

September 21, 1929: The College welcomes first-years to campus with a set of traditional rules

For incoming first-years, the first weeks are a busy haze of learning the College basics outside of class: campus slang, essential geography — “where’s Resky again?” — and the best dining-hall desserts. This can be overwhelming for first-years, since aside from rules against things like hazing, bullying, and harassment, the College doesn’t outline specific guidelines for how to navigate life as a student.

In a 1929 edition, however, nestled between articles detailing the football practice schedule and the rules for rushing Greek life, lies a Record column outlining “traditional campus rules to be enforced for [the class of] 1933,” a strict outline of etiquette for incoming students to follow during their first year at the College.

The rules dictated what first-years could and could not wear, as well as what times during the year they were allowed to wear certain items — and which places they weren’t allowed to go and sit. “Freshmen must never appear on the street coatless until after the spring recess; freshmen must wear the regulation hat throughout the year in Williamstown,” the first rule reads.

The list includes many other sartorial guidlines. “Freshmen must not wear leather or fur coats in Williamstown,” the list continues. “Freshmen must not wear knicker-bockers or army breeches until after the spring recess. Freshmen and sophomores must not wear corduroys or moleskin trousers.”

The rules were prefaced with a vague but ominous warning: “Campus regulations governing the incoming class are identical with those of the last few years and must be strictly adhered to at all times.”

First-years weren’t just mandated to change the way they dressed but also the way they acted. “Freshmen must not sit in the center section of Walden’s theatre [now Images Cinema] unless accompanied by an upperclassman,” and “Freshmen must not walk on any grass,” the list continues.

The article also includes a suggestion from the All-Campus Committee proposing the inclusion of a rule stating that “reasonable deference must be shown by freshmen about the college to upperclassmen.”

“Although freshmen are not prohibited from leading ‘the Mountains,’ warning is made against its vulgarization, since it virtually amounts to the hymn,” it continues.

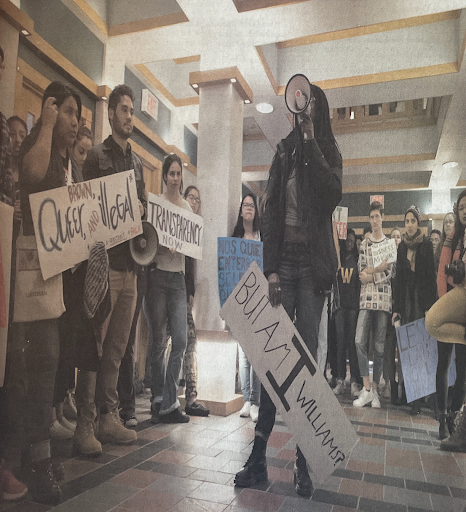

September 19, 1995: Students and faculty protest honorary degree awarded to Singapore’s prime minister, Convocation divided over student and faculty protests

In 1995, reactions to the College’s decision to confer an honorary degree upon Prime Minister of Singapore Goh Chok Tong were “many and varied,” the Record reported.

For Convocation, the theme of which was developmental economics, the College chose three awardees of honorary degrees, one of whom was Singaporean Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong CDE ’67.

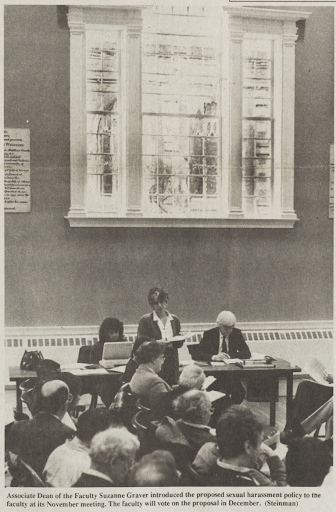

Prime Minister Tong’s recognition was met with significant uproar from faculty and students. A faculty statement quoted in the article writes that while the faculty “recognize the significant contributions Mr. Goh Chok Tong has made to the economic development of Singapore, we nonetheless find it regrettable for Williams College […] to have granted a duly enacted honorary degree to the Prime Minister of a government that has persistently failed to honor, protect, and promote the freedom of expression of its citizens.”

According to the Record, “the college experienced a convocation to remember.”

Many seniors protested during the ceremony. After a seniors-only meeting in Brooks-Rogers recital hall, some attended Convocation with white-felt squares over their caps in protest, because white represents the color of mourning in some Asian cultures, while others attended a separate convocation ceremony altogether in Science Quad to listen to “guest speakers Daniel Bell, former professor at the National University of Singapore and Chee soon Juan, leader of the Singaporean Democratic Party,” reported the article.

“In the space of one week, the College saw a counter convocation in the Science Quad, a man chaining himself to the doors of Chapin Hall, speeches by dissidents of Singapore, white felt squares pinned on seniors’ mortar board, a lively question and answer session with Goh, two last-minute meetings for the senior class and international media attention of a degree rarely seen in Williamstown,” the Record reported.

During the traditional walk from Mark Hopkins Gate into Chapin Hall for the main ceremony, a separate line of around 40 protestors, led by Assistant Professor of Political Science Sam Crane, walked parallel to the main procession, turning their backs to Tong as he passed, in an act of protest.

September 18, 2001: First-years compete in campuswide tradition

Traditions among first-year students to build community create a special bond during students’ first year at the College. Dodgeball and snowball fights in Frosh Quad, entry snacks, and movie nights live on as beloved customs passed down through generations of Ephs.

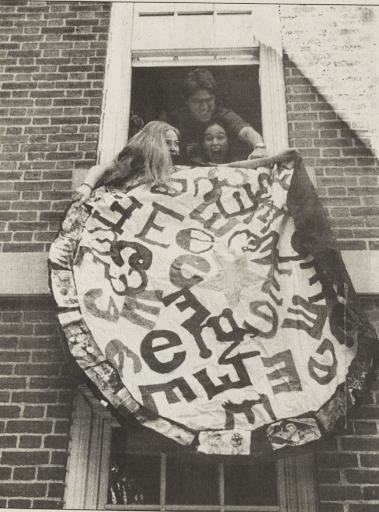

A tradition that has been lost to time, however, is the practice of banner theft. According to the Record, the banner-stealing tradition would begin with each entry displaying a banner across the walls of Frosh Quad and the other first-year dorms.

Entries got creative with their banners, creating designs that included “a stuffed cow, a colorful pin-wheel, and an amalgamation of concrete, chains and iron,” as described by the article.

The banners were safe during First Days as first-years arrived at the College, but after Sept. 2, “banners became fair game in a contest between entries to collect as many as possible while guarding their own.”

Scheming entries used their cunning and distraction to succeed in banner-stealing endeavors. Historical interviews recount members of the Williams B entry storming Sage D, and how “the ladies toilet-papered the inside while the guys watched one entry mate climb the outside of the building to reach the cow.”

Once the banners were stolen, they hid them in closets and behind locked doors. That year, however, an entry in Morgan displayed “chains of stolen banners out windows that overlook[ed] Spring Street.” Such boldness led to the recapture of some of the banners as first-years snuck in through Junior Advisors’ windows and used Swiss Army knives to reclaim that which was once theirs.

Perhaps it is the responsibility of the current class of first-years to resurrect this game.