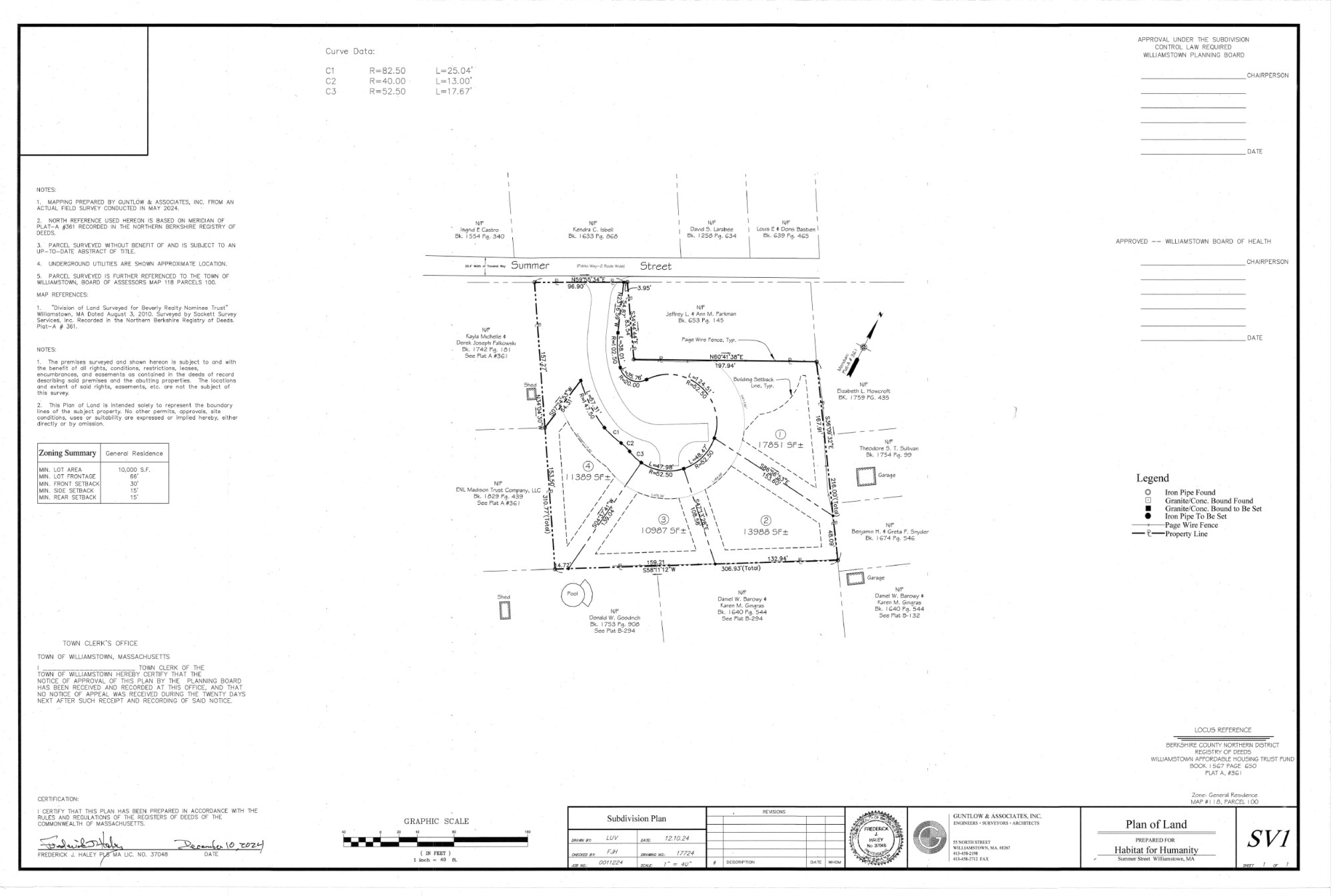

The Williamstown Planning Board approved Northern Berkshire Habitat for Humanity’s application to develop a 1.75-acre lot on Summer Street in the Town’s White Oaks neighborhood at its Jan. 14 meeting. Habitat for Humanity is set to acquire the land from the Williamstown Affordable Housing Trust (AHT), and the development, which will be called the Meadowlands Subdivision, will comprise four 1,200 square-foot houses for residents earning 30-percent to 60-percent of the Town’s median income.

The Meadowlands Subdivision aims to address the high cost of living in the Town, where the cheapest homes cost around $289,000, according to Northern Berkshire Habitat for Humanity President and Project Manager Keith Davis.

The homes’ sale prices will be determined based on residents’ ability to pay, according to Davis. Total costs, including mortgage payments, interest, and insurance, will not exceed 28 percent of a resident’s annual income. “We try to actually gear towards families that have steady employment,” he said.

“They’re good homes … and they’re also going to stay affordable because of their square footage,” he continued. “It gets a family a house [and] the chance to build some generational wealth … so it’s a really wonderful program.”

The subdivision will be accessible through a road called Austin Lane, which will be built specifically for the development. In keeping with the character of the surrounding neighborhood, the subdivision will not include sidewalks or streetlights.

Before breaking ground, the project’s definitive plan must be signed by all members of the Planning Board. Then, a 20-day public appeal process begins, during which owners of abutting properties can appeal the board’s decision. After this period, Habitat for Humanity will open bidding processes in which local contractors will offer a quote to build the road and foundations for the houses.

Davis said that he expected the bidding process for the road to begin in February. Should work progress smoothly, contractors will also complete the first foundation before framing begins in July. The remainder of construction will be carried out by volunteers. Habitat for Humanity hopes to complete the first house in spring 2026 and finish one every year beyond that, he added.

Although the bulk of the construction work will be done by volunteers, Habitat For Humanity expects to spend around $200,000 to build each home, mostly due to the cost of materials and hiring contractors to build the foundations. Davis noted that a typical homeowner will pay thousands less than the cost to construct the home, requiring Habitat for Humanity to raise the remaining funds. “I spend a lot of my free time trying to write grants,” Davis said. “We have to raise some money — it’s that simple.” Other sources of funding include fundraising events and direct appeals to donors, Davis added.

The AHT acquired the vacant lot in 2015 for future affordable housing development, and the lot remains under the AHT’s ownership. The transfer to Habitat for Humanity is set to be finalized only after all Town approval processes are complete.

“The AHT provides large grants that subsidize construction, enabling the final cost to be lower,” Professor of Political Science and AHT board member Cheryl Shanks wrote in an email to the Record. “We can provide land, as we did with Habitat, or money.”

After acquiring the lot, the AHT solicited proposals for its development, Shanks said. Habitat for Humanity submitted the only bid, according to Davis.

Despite the straightforward bidding process, the project — which initially included five homes — met resistance from neighbors, who wanted a scaled-down development. Following public comment on the preliminary plan and an environmental review, Habitat for Humanity revised its proposal to include only four homes.

“Subdivision usually sees a fair amount of resistance from neighbors, period,” Charlie LaBatt, senior engineer at civil engineering firm Guntlow & Associates said. “[Residents are] always resistant to change.”

“I wish people would not always react to change as a negative,” said Andrew Groff, the Town’s community development director. “There’s positives to this … more kids for your kids to play with, more neighbors to help you out when your snow blower is broken.”

Once complete, the Meadowlands Subdivision will sit on the southern edge of White Oaks, an area that has historically had a sizable Black population. Nadia Joseph ’25, who is writing a thesis on the history of the Black community in White Oaks, explained that Black residents were pushed out of the neighborhood in the 19th and 20th centuries amid white supremacist activity and gentrification.

Citing a need for new housing in the Town, Joseph said she supports the development. She noted that White Oaks was relatively inexpensive before the Black community’s displacement. “An affordable housing project almost seems ironic,” she added.

Shanks noted that the Town can further increase the availability of affordable housing by removing regulatory barriers to construction and requiring homes to be owner-occupied. LaBatt, for example, was forced to seek exemptions from certain regulations governing subdivisions, including decades-old provisions on drainage that Groff said “made no sense” given current engineering best practices.

The Town is looking to streamline the process to build affordable housing in the near future, Groff said. It recently received a state grant to fund a two-year comprehensive audit and rewrite of the Town’s subdivision rules to simplify the planning process for new housing.

“We need to do a lot of work in reforming our subdivision rules so it’s easier for the market to create market rate housing, and we’re working on that,” Groff said.