The White Oaks neighborhood has a hidden racist history connected to the College

November 30, 2022

About a five-minute drive from the College is the secluded neighborhood of White Oaks. Although it is a relatively unknown part of the Town to students, the College has had a long relationship with White Oaks, starting with the College’s construction of the White Oaks Congregational Church. The church, which now has a sign reading “All Are Welcome” above its entrance, was once home to Ku Klux Klan (KKK) meetings.

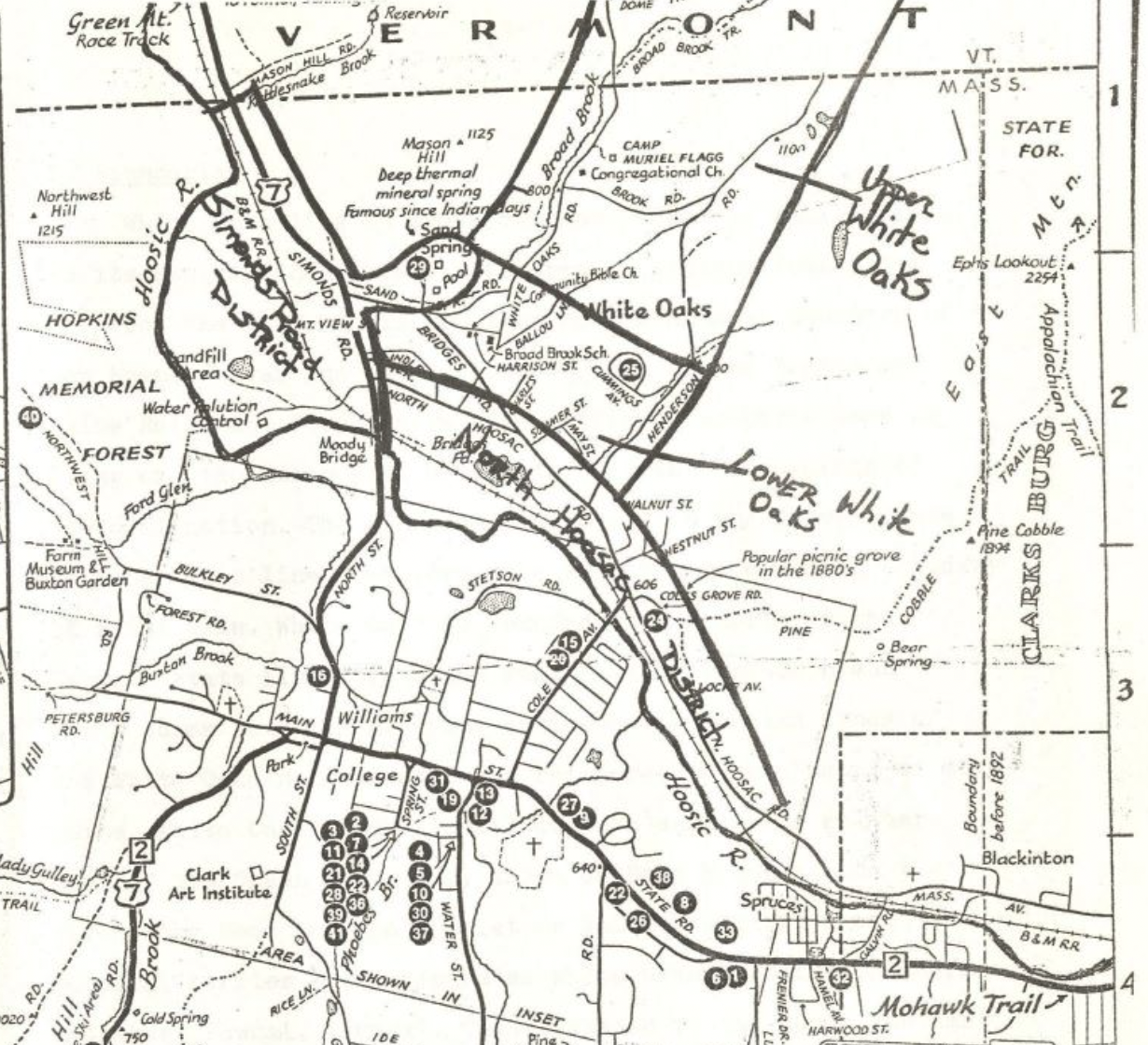

The neighborhood of White Oaks is situated in a uniquely isolated part of the Berkshires. The bounds of White Oaks are marked by mountainous state and town lines, railroads, and the Hoosic River.

“In areas around America where [isolation] exists, racism thrives,” Assistant Vice President for Campus Engagement and Interim Co-Director of the Davis Center Bilal Ansari said. Ansari is a White Oaks resident and has deep generational ties to both the neighborhood and the College. His ancestors were residents of White Oaks, and his great-grandparents lived and worked in the Chi Psi fraternity house, now Spencer House. His great grandmother was a cook and cleaner for the house, while his grandfather worked in the yard.

At first, the geographical seclusion White Oaks offered made it a safe haven for Indigenous and formerly enslaved people. “This was a place of refuge along the Underground Railroad, a place where the formerly enslaved took refuge here [in] what was primarily woods and predominantly white oak trees,” Ansari said.

In the 1800s, the Black population of White Oaks was estimated to make up 15 percent of total White Oaks residents, according to “A History of White Oaks Neighborhood in Williamstown, Massachusetts,” a senior thesis by Wayne Eckerson ’80. Albert Hopkins, brother of Mark Hopkins and professor at the College for 40 years, saw White Oaks as the ideal site for a church becuase of the high concentration of Black residents, whom he found in need of Christianity. Albert Hopkins was a religious man, dubbed the “Bishop of the Berkshires.” “Everybody would fall asleep during services except for when Albert Hopkins spoke,” Ansari said. “They said when he spoke, he had a command — people would sit on the edge of the chairs.”

In 1866, Hopkins built the church with financial support from various donations. The church was built in memory of his son, Edward Hopkins, who died in 1864 during the Civil War before his senior year at the College. “Albert writes in his memoirs that his only hope and desire for his son was to graduate from Williams College and go to Africa and build a mission to civilize the Black Africans,” Ansari explained. “The next year, Albert starts raising money to build [a church] in White Oaks … to honor the vision that he had for his son.” The purpose of the church was not only to memorialize his son but to civilize the Black residents of White Oaks. “If he couldn’t build that mission in Africa, well, there was a community of sons of Africa right here in Williamstown,” Ansari continued.

This racialized use of the church was amplified in the early 1900s when the KKK started to host meetings there. “There were hundreds of cross burnings that terrorized Black residents and frightened and scared them down to Pittsfield,” Ansari continued.

The decline in the Black population can be attributed to a combination of White supremacist activity and gentrification. “The community [was] decimated, because the original intent [of the church] was to purify, to clean it up,” Ansari said. “And that’s what happened to my ancestors. They were pushed out … and buried in unmarked graves. I’m still trying to find the bodies of my ancestors here.”

Though White Oaks has long been gentrified, Ansari continues to push for accountability from both the church and the College, whether that be in the form of reparations or a public acknowledgement of the area’s anti-Black history.

Other institutions of higher education have attempted to grapple with their racist pasts. In 2021, Yale University made a public statement of its involvement in slavery. In 2003, Brown University began its own investigation into its relationship with the transatlantic slave trade and later, in 2006, released its Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Williams, on the other hand, has yet to publicly acknowledge the role it played in the displacement and dispossession of Black people in White Oaks.

“We should have markers [in Williamstown] and memorials about the Black ancestors who were just here to survive,” Ansari said.