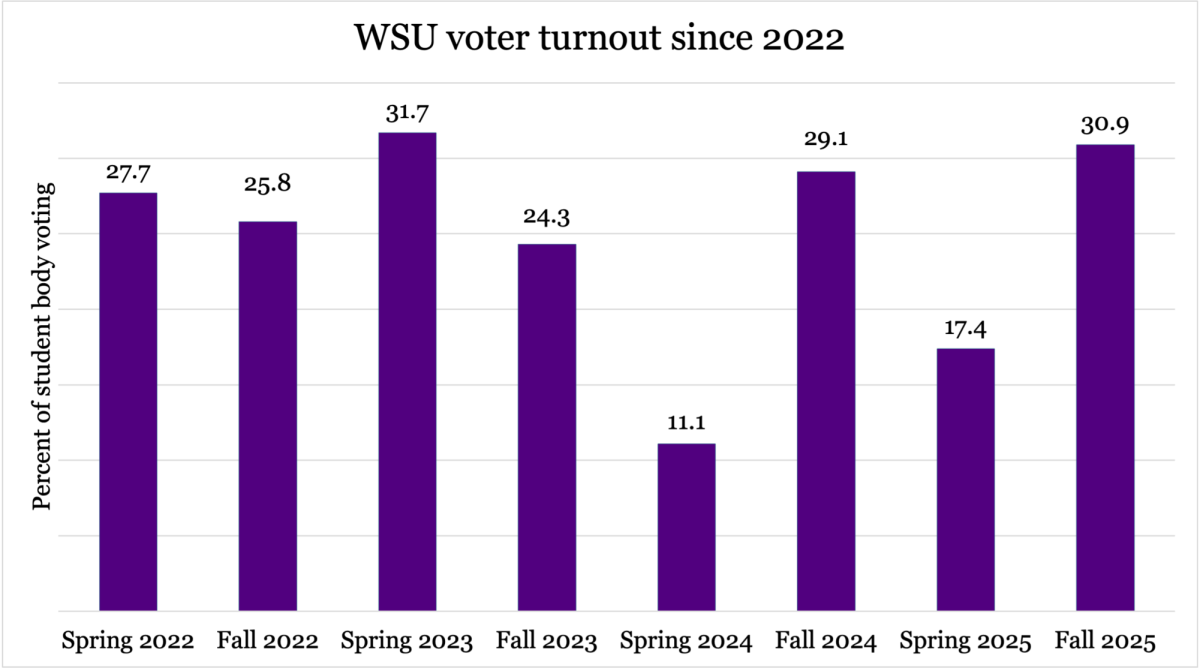

Seventy-six percent of all letter grades awarded in classes were an A+, A, or A- during the 2023–24 academic year, and 50 percent of grades were an A, according to data from the Office of Institutional Research (OIR). Twenty-five years ago, by contrast, A range grades comprised just 21 percent of grades.

OIR compiled the data this fall in response to a request from the Committee on Educational Affairs (CEA). At the faculty meeting today, faculty members will discuss a memo from the CEA about the history and current status of grade distribution reports at the College. The Faculty Steering Committee included the memo in the agenda for today’s meeting, which it distributed to faculty on Oct. 30.

Prior to 2019, faculty members received two reports on grade distribution each year. After each faculty member submitted grades for the semester, they received a report from the registrar’s office comparing the faculty member’s mean grades issued to the mean grades issued in their department and division. At the end of each year, each faculty member also received a report detailing the average grade given in every course level of a department’s offerings.

The semesterly report also included course grade targets: a 3.2 average for 100-level courses, 3.3 for 200-level courses, 3.4 for 300-level courses, and 3.5 for 400-level courses, which were approved by a faculty vote on a motion from the CEA in 2000.

In 2019, the Record obtained that year’s report, which stated that the average GPA at the College was 3.52. Based on the CEA memo, the Record calculated that the average GPA for the 2023-24 academic year was somewhere above 3.65 — the CEA’s 2024 data also includes grades designated Pass/Fail, so the actual average GPA is higher than the chart reflects.

After spring 2019, the registrar’s office stopped sending both reports. In the memo shared in advance of today’s faculty meeting, the CEA wrote that the reports stopped “for a variety of reasons.” Sara Dubow, faculty chair of the CEA, wrote in an email to the Record that she could not find out why the office discontinued the practice. “The committee and I are more focused on figuring out what to do going forward,” she said.

In its memo, the CEA told faculty that it hopes to discuss how useful the reports were and whether the registrar’s office should resume distributing them at today’s meeting.

Sophia Nogueira ’27, student chair of the CEA, told the Record that the conversation is intended to collect faculty perspectives before the CEA moves forward with any plans. “We want to go into the faculty meeting on November 6 with an open mind,” she said. “We didn’t want to bring a motion without discussing with the faculty.”

Nogueira added that the CEA is focused on deciding whether to resume the reports but that its conversations have also touched on the broader issue of grade inflation at the College. “We discussed how this might bring up larger conversations about values and the culture of the College, specifically surrounding grade inflation and compression,” she said.

At the end of the memo, the CEA included a chart showing the distribution of grades awarded to students in a course from the 1985–86 academic year until the last academic year. In that time, the rate at which students receive As has nearly quintupled, from 11 percent in the 1985–86 academic year to 50 percent in 2023–24.

After the CEA collects faculty opinions, Nogeuira said, its members will start exploring possible motions to bring to future faculty meetings. “Once we feel like we have substantial information and have taken the temperature of most faculty on campus, then we would return with the motion,” she said.

In interviews with the Record, several faculty members expressed concerns about grade inflation in light of the CEA memo and the grade frequency chart included in it.

Professor of Political Science Justin Crowe said he believes that grade inflation has decreased student learning. “Many faculty — certainly I include myself in that — have seen that grades are something of a motivator for students,” he said. “It’s important to give students honest feedback so they know what they’re doing well, what they’re doing less well, [and] so they can decide whether they want to put the work in to do better.”

Crowe added that he’s observed that grade inflation increases student stress around grades and discourages academic exploration. He noted that a B+ is now in the bottom third of grades awarded to students. “That puts so much pressure on any individual paper, on any individual course, and it sends students’ anxiety and stress through the roof, because there is effectively no margin for error in a world in which the only good grades are A, A+, and A-,” he said.

“If we have a world in which grades aren’t quite so inflated and quite so compressed, then getting a B+ isn’t the end of the world, because everybody’s getting a B+ every now and then,” he continued.

Professor of Statistics Richard De Veaux attributes continued grade inflation to the College’s reliance on Student Course Survey (SCS) scores in tenure decisions and a perception among junior faculty that awarding higher grades improves their SCS scores, thus increasing their chances of securing tenure. “The young faculty perceive that to give low grades, to give Bs and B+s, is certainly not — they think — the road to a safe tenure evaluation,” De Veaux said.

De Veaux said that it’s difficult for the College to address grade inflation because the problem is widespread across undergraduate education, and grading students more harshly would put them at a disadvantage for graduate school admissions.

Professor of Biology Luana Maroja said she believes that grade inflation hurts aspiring medical students. “Medical schools still take the standardized exam, the MCAT, for which, of course, you need to learn things in order to do well,” she said. “Removing the incentives for learning because everybody’s getting As is a problem.”

Crowe and Maroja both said that the grade distribution reports had been a valuable tool prior to their discontinuation in 2019. “I think they’re important for us as individuals to know what we’re doing in the context of the College,” Crowe said.

He described grading as a collaborative project across the faculty, where professors rely on each other to maintain grading norms. “I think the reports are also important for the College so we can see where other departments are, where we are in the divisions, so that we have a sense of this enterprise that we all engage in,” Crowe added.

Maroja said that when she began teaching at the College, she based her grading off of the targets outlined in the grade distribution reports. “When I first came as a professor, I had no idea how to grade, and they were a guide to me,” she said.

De Veaux, however, expressed concern that the CEA’s memo and the possible return of the grade distribution reports might speed up grade inflation. He noted that, before the memo was released, faculty didn’t know the rate at which As were awarded. “Now, [professors might think,] ‘Oh my God, 70 percent [of courses] give As. I’m not going to punish my students and give them a B+ unless they’re really at the bottom 30 percent.’”

All three professors expressed support for bureaucratic change at the College to address grade inflation, though their suggestions differed. Crowe suggested putting the average grade in each course next to student’s grades on their transcripts, while Maroja proposed reporting the average GPA at the College on transcripts. De Veaux suggested encouraging faculty to award A+ grades to allow for a higher ceiling and to reward excellent student work.

Nogueira emphasized that, while conversations at the faculty meeting will likely cover grade inflation more broadly, the CEA’s specific focus is on the future of the grade distribution reports.

“I think faculty have a lot of thoughts on [grade inflation], and we’d love to hear their feedback,” she said. “But for now, we’re just trying to focus on the memos and see if that opens up other conversations to be had.”