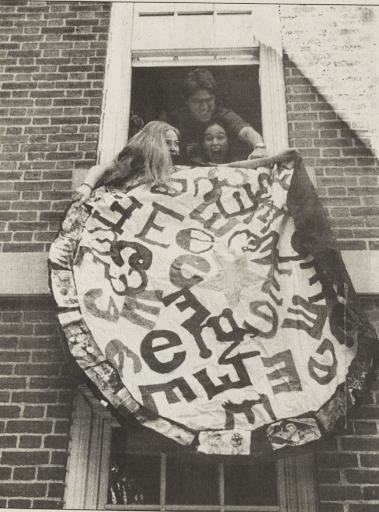

“That’s so The Secret History.” You could use the phrase to describe the grand fireplace in Stetson Hall’s 24-hour room or the wood-paneled reading room on the ground floor of Sawyer Library. Maybe as an allusion to the College’s bucolic backdrop — its rolling mountains turned burnt orange in the autumn, the knee-deep snowfall and biting winds come winter. Or it could be used as a jab at a particular Williams archetype: the student perched on the steps of Chapin Hall, donning a dark Burberry trench coat, who puffs Marlboros and ponders ancient Greek philosophy.

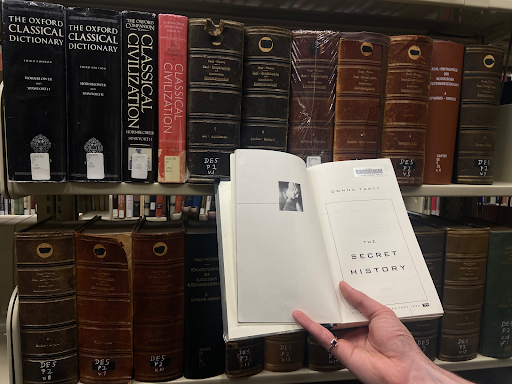

Neither the classic intellectual nor the ivory towers within which he reigns are the literary inventions of Donna Tartt. Nonetheless, in the 30 years since the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer penned her debut novel, The Secret History has become a quintessential portrayal of life and study for the Williams student.

Tartt began working on The Secret History at 19 as an undergraduate at Bennington College, the liberal arts school 20-odd miles north of Williams, widely considered to serve as inspiration for the novel’s setting. She graduated from Bennington in 1986 and published the novel six years later.

At the novel’s outset, Richard Papen, The Secret History’s narrator, enrolls at the fictional Hampden College — a 500-student, highly selective liberal arts institution in rural Vermont — captured by its brochure, which advertises, alongside the storybook beauty of rural New England, a school that provides its students “not only with facts, but with the raw materials of wisdom.”

Richard, vastly less wealthy than his peers, is an immediate outcast at Hampden. Through his desire to study Greek, he finds himself under the instruction of Julian Morrow, the college’s eccentric classics professor, who limits his course enrollment to a hand-selected six students and requires them to take classes only with him. Though Richard finds a sort of community among this academic clique — he’s invited to spend weekends with the sextet at one of their country homes — his first year is anything but ideal.

In the now-iconic opening lines of the novel, Tartt introduces its climactic tragedy: “The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny” — one of Richard’s five classmates — “had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.”

There are certainly exaggerations in The Secret History’s account of liberal arts life — murderous Bacchanalia, for one — but in a series of interviews with the Record, students and faculty said that The Secret History captures an ounce of truth about the experience of attending a small liberal arts college in New England. For some, it depicts the academic ideal to which Williams strives: total immersion in study and deeply enriching intellectual relationships with professors. For others, it appropriately satirizes — and even condemns — the most pretentious at Williams. And for many, it is a bit of both.

Take the mythos of the student-professor relationship at Williams. The College’s website boasts that “students receive an education both deep and broad, thanks to the close relationship between teacher and student,” aided in part by its slim seven-to-one student-faculty ratio. In Richard’s experience at Hampden, that ratio is six-to-one.

“In places like Williams, they promote intense intellectual relationships between students and faculty,” said Professor of English Christian Thorne, who first encountered the novel one summer while he was still in graduate school. “The campus bar is named after one such relationship.”

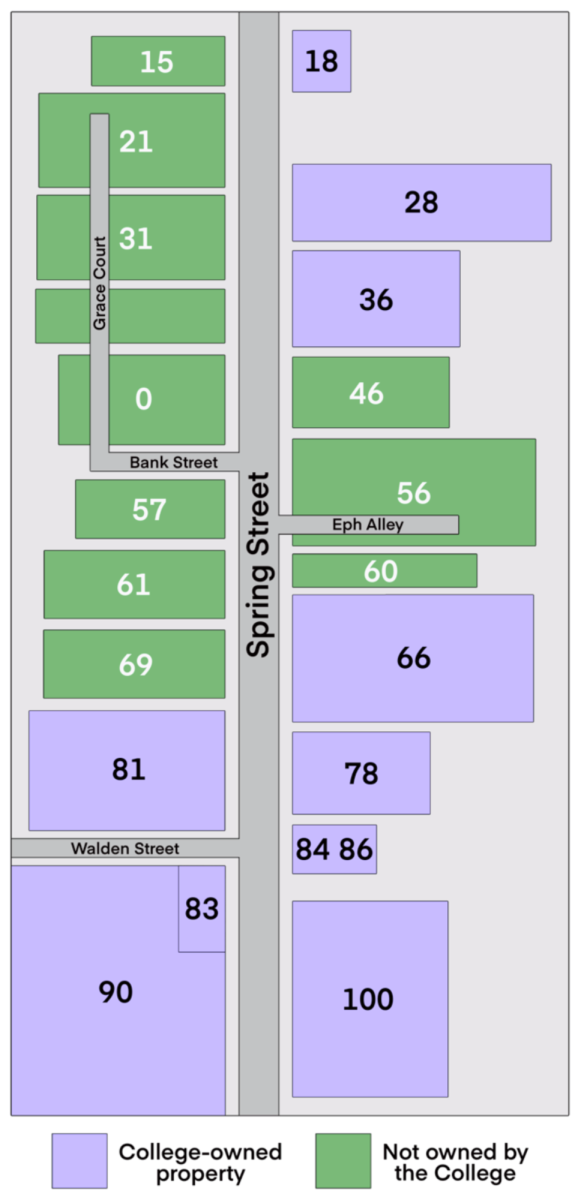

(“The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log and a student on the other,” James A. Garfield, Class of 1885, famously said of the former president of Williams. The Log, the campus bar Thorne referenced, now sits at the base of Spring Street.)

In terms of classroom structure, then, it would appear that the portrait painted by The Secret History is not that far from life at Williams. Felix King ’25, who listened to an audiobook version of The Secret History twice last summer, said that Julian’s courses are “kind of analogous to a tutorial — or closer to a tutorial than a typical seminar.”

Students at Williams studying classics — a notably small department composed of six active professors and two professors emerita — have a unique opportunity to develop personalized relationships with each of the faculty members, similar to that in the novel.

“I think it’s really special that there are so few professors and you get to know them super well,” said Kevin Jiang ’26, a classics and math double major who read The Secret History last summer upon a friend’s recommendation. “In that sense, yes, it is kind of similar,” he added.

“I do feel that connection,” echoed Sam Sidders ’25, a classics and geosciences double major. “I feel like I could go to any of their offices and ask them about anything and it would be totally chill.”

The novel is rather skeptical of close ties between professors and students: The students in The Secret History worship Julian — on one occasion calling him a “divinity in our midst” — and their more murderous actions could certainly be chalked up to his influence.

Williams, Thorne said, is also dubious of the potential for exploitation, and there are structural limitations to relationships between faculty and students as a result. “There’s no way to attach yourself to somebody here in the mode of discipleship,” he said. “Everything is set up to rotate students from professor to professor to professor.”

“In the English department, it’s not uncommon for a student to feel like they’ve learned a lot from a professor and to go back for second or third helpings,” he continued. “But what does that mean — they’ve taken maybe three classes, and then they write a thesis?”

Even programs that promote a closer connection between professors and students — Lyceum and Doddceum dinners, for instance, where students can invite faculty to share a meal — draw clear boundaries.

“I feel like it’s a safety net because that means it’s happening on campus — it’s very transparent,” said Lecturer in Music Anna Lenti of meals between students and faculty.

Lenti first encountered The Secret History about a decade ago and is now in the middle of a re-read. Despite her love for the novel, she said Julian’s persona — that of an academic deity — is not one she would ever try to replicate in her own classroom. “I don’t glorify him at all,” she said. “I want to be seen as human by my students. That’s my number one goal.”

“The depictions of relationships between students and faculty are scandalizing,” Professor of English Gage McWeeny said of the novel. “But it also took seriously the energy of that pedagogical relationship, even as it condemns its potential for abuse.”

In 2018, McWeeny offered the 100-level English course “Campus Life: The University and the Novel,” which explored “the scholarly and sexual intrigues of the college campus” as described in post-World War II American literature, per the course’s catalog description. Naturally, The Secret History was a core fixture of the syllabus.

During his opening class, McWeeny asked his students to share a book that they were ashamed to have or have not read. “One of my students said he was slightly embarrassed to have read The Secret History in preparation for coming to Williams,” he remembered.

As he was creating the syllabus for the course, McWeeny said he wanted to include Tartt’s novel because of how it differs from the typical campus novel — its approach is far more sobering and significantly less satirical than others in the category. However, he was worried about how it would land with his students. “It might feel outdated — like, who are these weirdos preoccupied with Ancient Greek?” McWeeny said. “It turned out they loved it.”

For his students from cities and warmer climates than Williamstown, McWeeny observed a resonance in the novel’s “small town-ness” and its portrayal of an especially harsh New England winter — even if most Californians at Williams don’t share Richard’s experience of nearly dying from the cold during their first year.

McWeeny’s students were also interested in the novel’s unusually intimate classroom arrangement, which he said elucidated “that thing that can happen in a classroom” where students develop strong intellectual bonds, even if they are not necessarily friends outside of class. In The Secret History, the strength of that bond is so strong that it leads them to perform cult rituals in the woods.

“There’s not a word for the distinctive nature of the relationship that you form with other people in a classroom,” he said. “My agenda in this class was to encourage them to take seriously those kinds of relationships,” he added — and to even create them with each other, though “minus the murder.”

Perhaps most dissimilar to the study of classics at an institution like Williams, according to Grace Newman ’26, is the novel’s portrayal of students singularly devoted to the discipline.

Newman, a double major in classics and comparative literature, read The Secret History to write a 10-page paper in high school. At that point, she knew she was interested in pursuing classics and said she was drawn to the novel for its portrayal of what that study could look like. She even considered applying to Bennington after she finished.

However, at Williams, the disparities between the novel and reality were immediately evident.

“A lot of classics majors are double majors,” she said. “I feel like there’s a lot of people applying different frameworks to classics, as opposed to classics dictating the framework in other areas.”

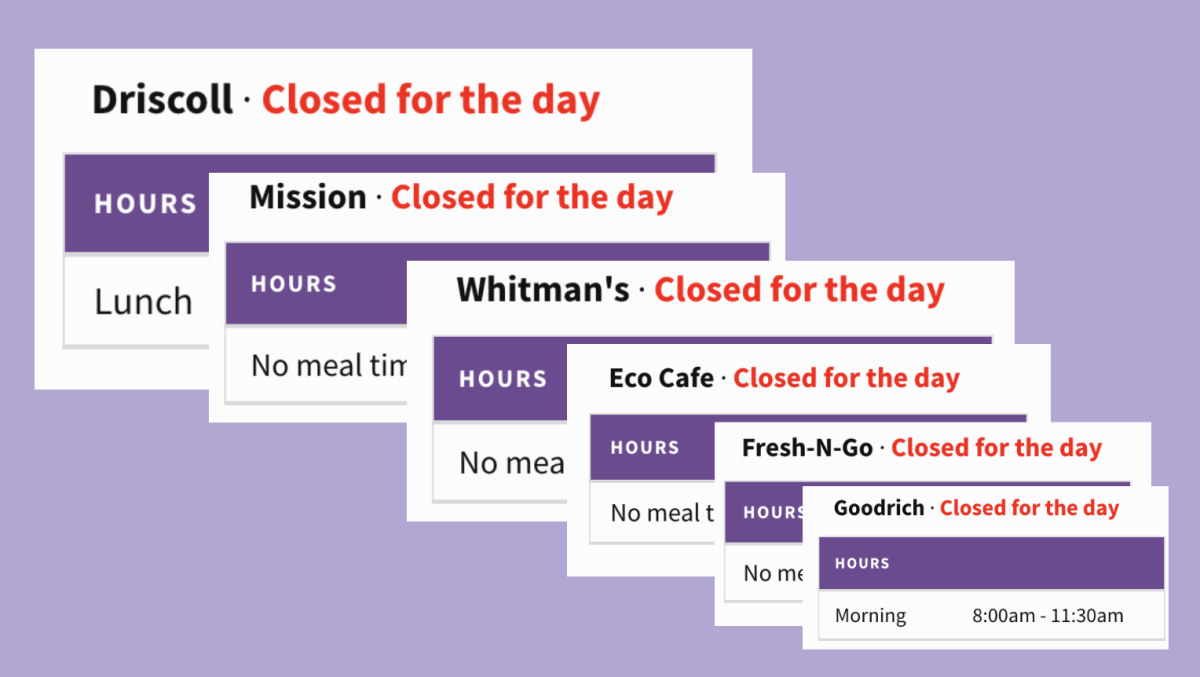

Students at Williams also juggle much more than just their studies.

“Students here tend to be doing 30 things at once,” Thorne said, calling the novel’s portrayal of a sole dedication to academic study “most un-Williamsite.” “Williams, to some extent officially, but even more in its self-created student culture, expects people to be constantly running from one thing to the next and fitting their schoolwork in as they may.”

Nonetheless, for some, this fantasy remains an idealized version of Williams, especially as higher education becomes increasingly fixated on pre-professionalism. On Richard’s first day of class with Julian, his esteemed professor prepares the small seminar for their academic journey, asking them, “I hope we’re all ready to leave the phenomenal world, and enter into the sublime?”

“I think they felt a little bit liberated by it,” McWeeny said of his student’s reaction to the novel’s fantasy of academic immersion, especially one so distant from careerist aspirations. “I think under the best circumstances, a college classroom could feel something like that — that you would enter into a different world.”

“I like that that book opens up, in a pathologized form, that possibility for [students] — that this is a relationship one could have to study,” he continued. “To go all in on something is an underappreciated part of what you get to do in college.”

Though largely absent for many at Williams, glimmers of that fantasy still exist — at least for Sasha Tucker ’25, a classics and English double major at Williams. Tucker first read The Secret History on a family backpacking trip in Colorado, finishing the novel in a single night while in the throes of altitude-induced fever. Similar to Richard, she studied ancient languages in high school and had some inkling she would continue to in college. “It was important to me but not the centerpiece of my life,” Tucker said.

But at Williams, she was captivated by her classics professors. She traveled with the department to Greece during the Winter Study of her sophomore year, used departmental funding to conduct language study in Germany, and spent a semester studying classics in Rome. During her semester abroad, a friend challenged Tucker to speak only in Latin for a day — not unlike how Julian’s disciples frequently communicate in Ancient Greek throughout the novel. “It was pretty exciting,” Tucker said. “A little ridiculous, but really wonderful.”

The immersion has only continued as she starts work on her classics thesis, which explores Latin poetry.

“We don’t want to give a thesis to someone unless you’re obsessed with it,’” Tucker recalled her thesis advisor telling her at the beginning of the semester. “I want you to see your thesis everywhere. I want you to point at everything you see and be like, ‘That’s what I’m writing about. That’s what I’m thinking about.’”

But even if she gives her all to classics — maybe even venturing into the world of the sublime — there are not quite the same opportunities for ritualistic practice at Williams. There’s the Nostos celebration, named in reference to the Greek theme of homecoming, where students and faculty can share stories from semesters and summers away from campus. The department sometimes marks the ancient Roman festival Parilia by bringing a small herd of sheep to campus. But Tucker is not attending a bacchanal at Hopkins Memorial Forest.

Or maybe that definition of ritual — one that ends in murder — is too narrow. For Lenti, ritual takes the form of spontaneously encountering students singing music from one of her courses around campus — which “does happen to me every so often.” McWeeny said he was once invited to a “futurist banquet” — a seven-course meal hosted in Dodd House with experimental meals (including tobacco ice cream, a treat served in a beaker, and irradiated meat), inspired by a 20th century Italian manifesto.

“I hope that those kinds of things are going on, where someone’s got some weird, dumb idea that takes serious their learning and plays with it,” McWeeny said. “At its best, that’s what should happen at the end of a class that I teach: My students will found some playfully cultish literary rituals or practices or experiments that they want to go do.”

Just no murder.