“I heard about it before I even came to Williams,” Chloë Braum-Bharti ’27 told the Record. What postulation was at the heart of such intrigue? The “Phantom 500.”

If you’re a student, it’s likely you heard about the Phantom 500 early in your time at the College — it’s a common Williams term like the “Williams swivel” and “snar.” It’s the idea that each student at the College will never meet or interact with 500 other Ephs during their time in Williamstown. Those 500 people, who are unique for each student, are their personal “Phantom 500.”

The origins of the concept are unknown. It’s referenced in an April 2016 College Confidential post by the anonymous user “jersey454,” who explained the Phantom 500 as a “term at Williams that floats around every now and then” describing the 500 students “you just won’t know.” It appears in a February 2019 Record article about a matchmaking Instagram account, which advertised itself as a way to meet “the people that we don’t really interact with and don’t really know but maybe would like to know better.”

But the term seems to thrive beyond the Purple Bubble: A post on the blogging site LiveJournal references the concept in a December 2005 post about Haverford College. (Lillian Leibovich, a senior at Haverford, confirmed to the Record that the phenomenon remains a topic of conversation on campus today much like at Williams — though it’s worth noting that Haverford’s student body is about 700 students smaller.) A student at Colorado College defined the term in an April 2013 blog post as “a mirage of students who exist somehow unseen and unacknowledged.”

Despite the College’s small size, students agreed that the Phantom 500 — or at least the underlying philosophy behind it — seemed to hold true.

“When I was applying to college, I was looking for a place where you can’t walk through the dining hall without seeing somebody that you know,” Casey Monteiro ’24 said. “And while I think that’s true, there’s also plenty of times I’m walking around campus, and I’m like, ‘I’ve never seen this person ever’ — which I think makes my experience better, because I’m always meeting new people.”

“At a small school, there are a lot of faces that you recognize,” Arthur Johnson ’26 told the Record. “Then, occasionally in [Paresky], you’ll see someone where it’s like, ‘Who the hell is that? I’ve never seen them before.’ It’s weird because everyone at Williams is, like, ‘two [degrees of separation] away,’ is the saying. To see a face or hear a name that you’ve just never heard of is crazy.”

Though students were familiar with the term, some had conflicting ideas of what the “Phantom 500” meant. When Braum-Bharti heard about the concept from other pre-frosh at Previews, it was described as a group of 500 “loners” that the rest of campus would never meet.

Johnson, who said he probably heard the term his first fall semester at the College, understood the term to explain why certain social events that would presumably draw the entire student body would not be as crowded as one might expect.

“Sensations was the big one,” he said, referencing the annual daytime party on Hoxsey Street. “The entire school should be out on Hoxsey — people are saying that — but it’s not particularly densely populated. It’s like, ‘Oh, there are probably people studying right now.’” To Johnson, those studious absentees were the Phantom 500.

The survey

In order to test this decades-old concept, the Record emailed a survey to the entire student body. Each participant in the survey received the names and class years of a different 50 students, who were randomly selected from the 2,164-student undergraduate population by the survey software Qualtrics.

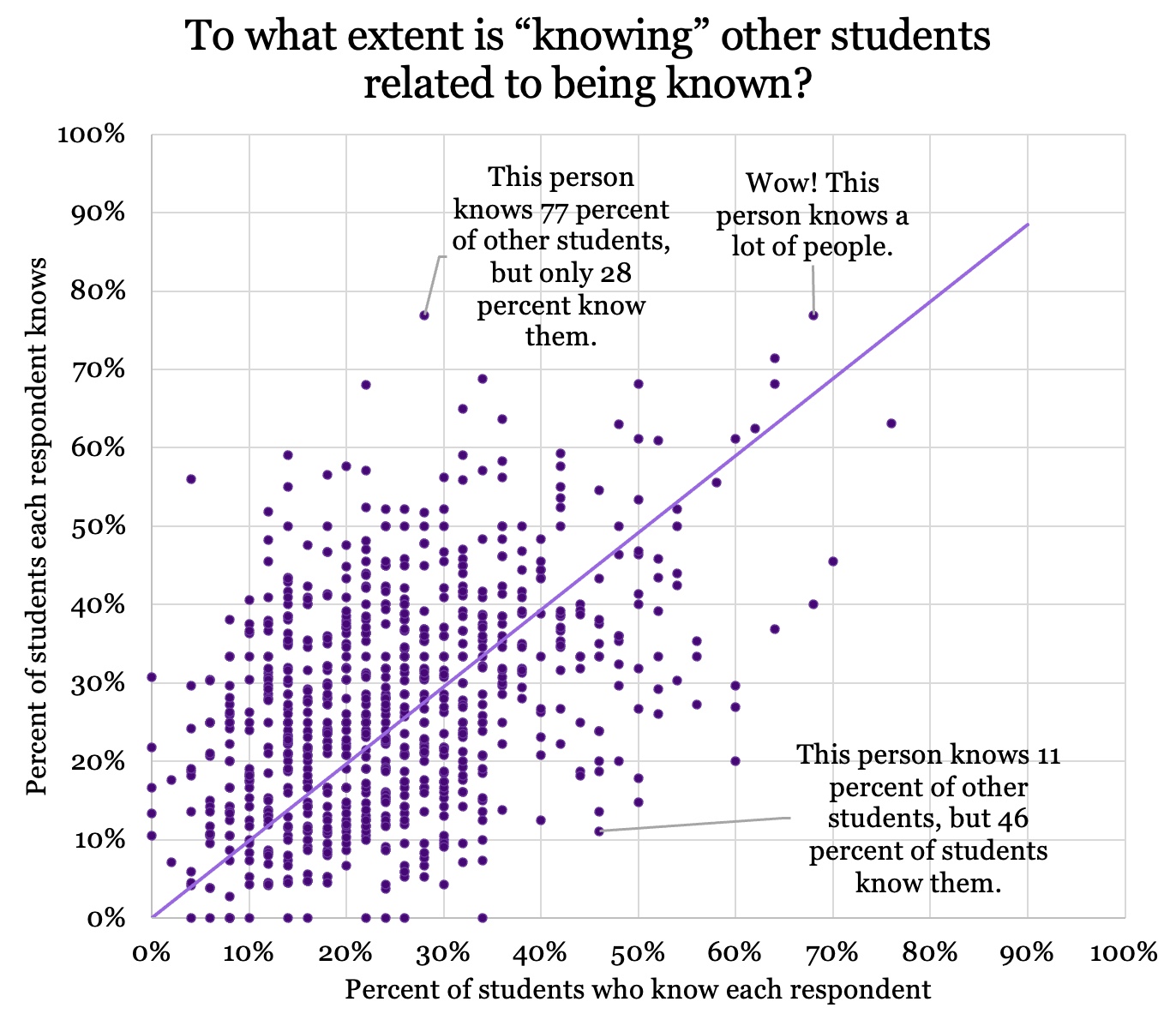

Participants were instructed to answer “yes” or “no” to knowing each student on their list. The Record defined “knowing” as being able to picture the person’s face based solely on their name and class year — without using social media or the “Facebook” feature of Williams Students Online. The responses were internally anonymous and each mapped to a unique code, untraceable to any student’s name — meaning no one, not even the Record, could tell how well-known any one student is (as much as we wanted to see our own results).

The survey received 1,045 responses — nearly half of the student body. Respondents were members of all four class years, with 251 first-years, 306 sophomores, 258 juniors, and 230 seniors participating, representing roughly half of every class year, though sophomores were slightly overrepresented in the results. Survey respondents were asked to round down if they were off-cycle — for example, respondents in the Class of 2024.5 listed themselves as “Class of 2024.”

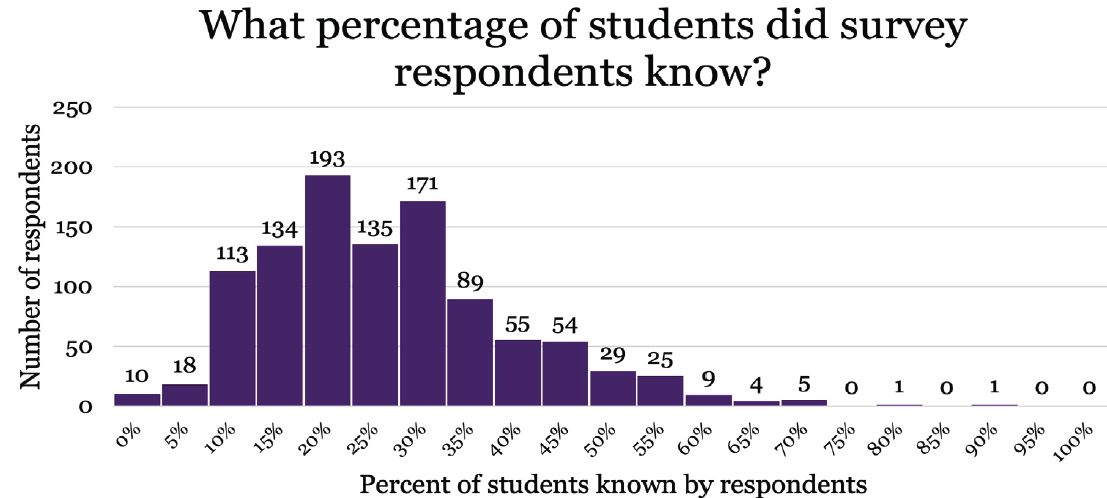

It seems that the Phantom 500 is a little bigger than the myth suggests. On average, students only knew about 24 percent — or 12 in 50 — of the names on their survey. When you extrapolate that rate proportionally to the entire student body, you get a much larger “Phantom 1,641.” If the Phantom 500 were accurate, students would have to know an average of 77 percent — or 38 in 50 — of the names on their survey.

But this didn’t come as much of a surprise to most students. Before they were given the list of names, students were asked to predict the percentage of names they expected to know. On average, they predicted they would know about 26 percent.

The survey was not without its outliers. Dylan Safai ’26, for instance, correctly estimated that he would know about 60 to 70 percent of the names, he told the Record. He attributed this to his role on Williams Student Union, through which he meets a wide array of students.

Demographic breakdown

The survey also collected several pieces of demographic information: class year, athlete status, major division, and semesters spent studying away. In interviews with the Record, students shared various predictions about the impact of these factors on social connectedness.

“I think [first-years and seniors] will probably know the least,” Johnson said. “In the two middle grades, we’ve been here for a while, so we know a lot of people, and we weren’t affected by COVID to the same degree.”

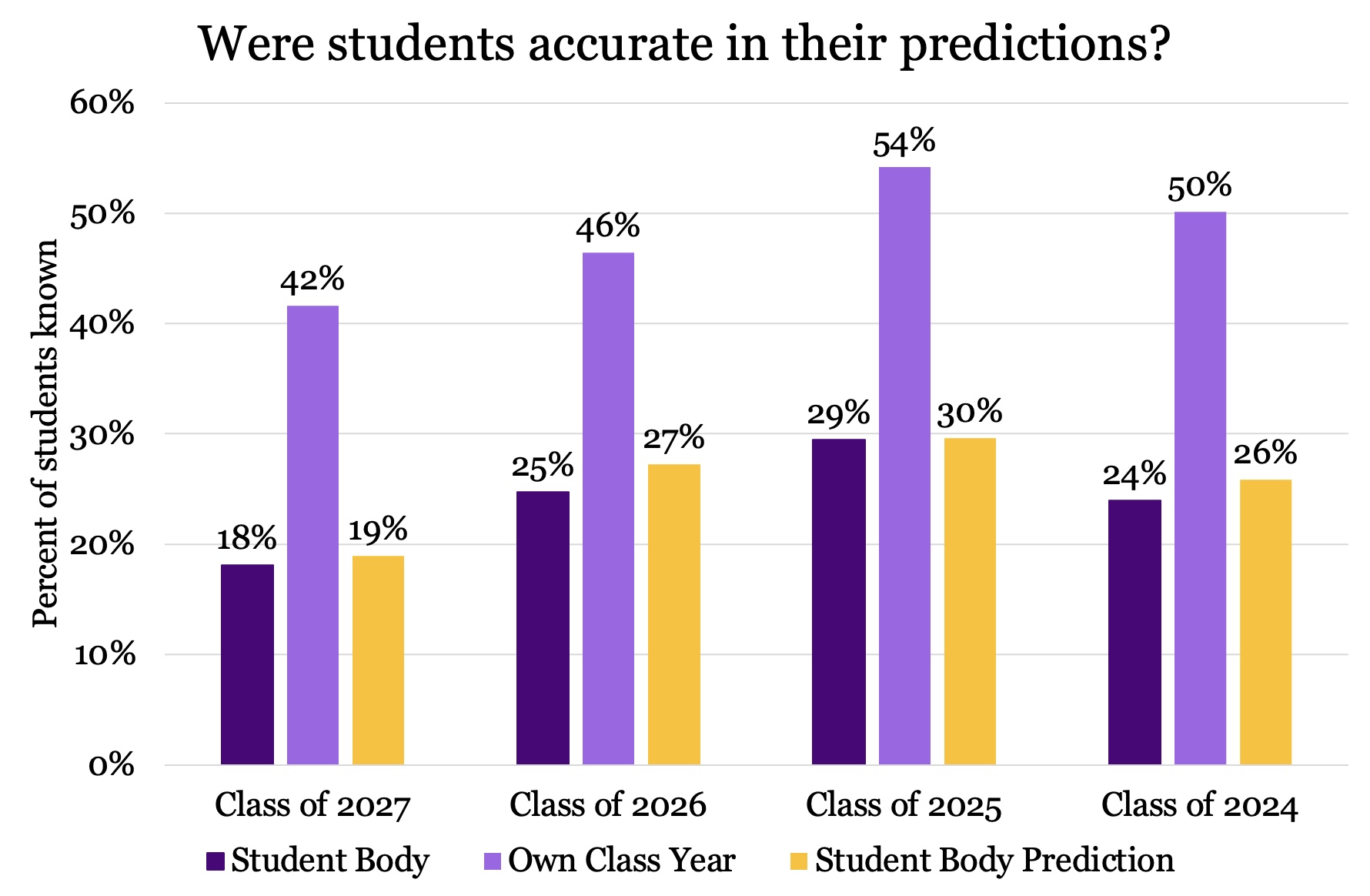

This prediction held true in the results, as juniors and sophomores knew the greatest proportion of the total student body. The Classes of 2025 and 2026 knew an average of about 29 and 25 percent, respectively, while the Classes of 2024 and 2027 knew about 24 and 18 percent, respectively.

These were all within 3 percent of each class year’s average predictions — in other words, first-years, sophomores, juniors, and seniors accurately predicted they would know 19, 27, 30, and 26 percent of the student body, respectively.

Additionally, the classes that knew each other the least were first-years and seniors. Seniors only knew 7 percent of first-years, while first-years knew 13 percent of seniors.

Unsurprisingly, the results also demonstrated that students know members of their own class year at the highest rate. First-year students knew, on average, 42 percent of other first-years, sophomores knew 46 percent of other sophomores, juniors knew 54 percent of other juniors, and seniors knew 50 percent of other seniors.

Thus, on average, students knew nearly half of their own class year — though some participants expressed surprise at their lack of complete knowledge. “I think the really surprising thing was the people in my grade that I’d never heard of,” Johnson said.

Monteiro, a senior, noted that social connectedness among the Class of 2024 may have been stunted by pandemic restrictions in 2020 and 2021. “It is kind of freaky when … someone mentions someone who’s in my year, and I don’t know who they are, which may be a factor of the fact that we were a COVID class,” she said. This is possibly reflected in the dip from juniors to seniors in their knowledge of other members of their own class.

Other students predicted that major division and athlete status would significantly impact results. “I think Division 3 majors spend too much time in labs and stuff like that, so they don’t meet as many people,” Safai said.

The results, however, demonstrated that students majoring across divisions tended to know a nearly identical portion of the student body. Division 1 majors knew about 24 percent, Division 2 majors knew 25 percent, and Division 3 majors knew 24 percent.

The proportion of varsity athletes who completed the survey, 29 percent, closely matches the proportion of athletes at the College, 33 percent. Some participants also predicted that athletic status would impact results as well. “Athletes are very insular,” Safai said. “You stick with your friend group — you stick with your co-athletes. It’s no fault of theirs, but that’s what happens.”

However, once again, athletes and non-athletes who participated in the survey remained relatively similar in terms of social connectedness. Members of varsity athletic teams and participants who did not play varsity sports both knew about 24 percent of the student body.

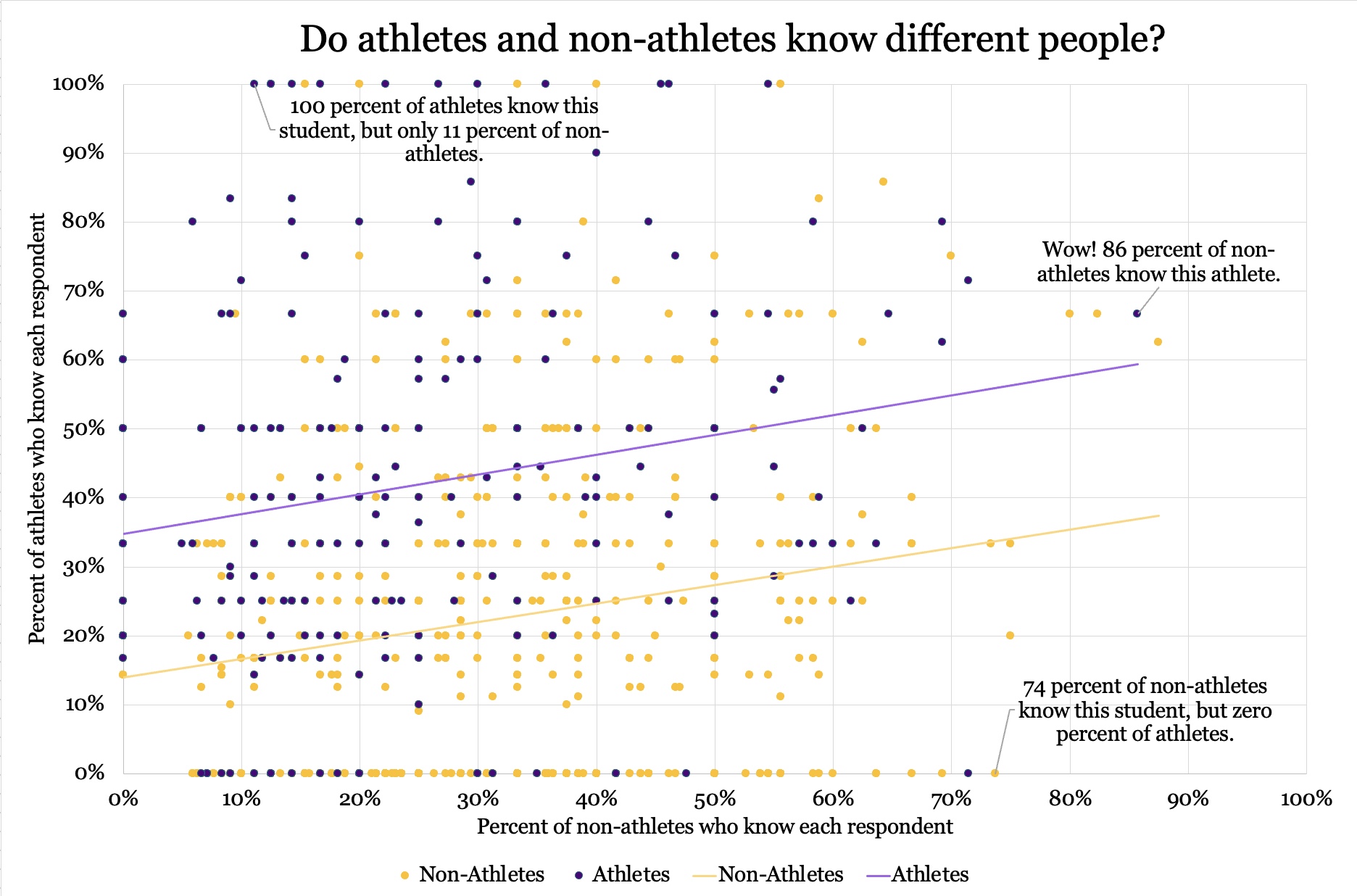

The data also helps to illuminate another age-old question at the College — is there a stark social division between athletes and non-athletes? The Record found that athletes who responded to the survey were known by about 40 percent of other athletes but only 22 percent of non-athletes. Conversely, non-athlete respondents were known by 30 percent of non-athletes and only 24 percent of athletes.

Studying away seemed to have a slight effect on the results as well. Seniors who did not study away tended to know an average of 26 percent of the College. However, seniors who studied away for one semester knew 24 percent, and those who studied away for two semesters knew 20 percent. Thus studying away seemed to decrease knowledge of other students by an average of 3 percent for each semester spent away.

Braum-Bharti said she expected that demographic factors would have a smaller impact on the results than individual motivation. “It really depends on the individual, I feel, and how much they try to go out of their way to know other people,” she said. “Because I think if you want to, you definitely can.”

However, she suggested that housing might impact connectedness within one’s class year. “I think probably living situations [have an effect],” she said. “In other years, I’ll be living around those in different years. But this year, I know, like, everyone on my floor and most of my building.”

“In PSYC 101, you learn that a lot of friendships happen out of convenience — you’re more likely to be friends with someone who’s next to you than someone who’s far away, so I think I’ve really taken that into account,” Braum-Bharti added.

When asked if he thought the results of the survey might change students’ approach to life at the College, Safai said he hoped it would. “At Williams, once you find a friend group you stick to that friend group,” he said. “I know at bigger schools, you’re always meeting new people, so you’re more open to getting to know the whole class. I wish Williams was more like that. I wish we got to know more people.”

Editor’s note: While we tried to get the survey to every student at the College, some emails bounced due to the large volume of outgoing emails. We estimate that between 100 and 200 students didn’t receive the survey. If that’s you, we apologize.