The art department closed its lecture series on Thursday, Feb. 29, with a talk and Q&A by Associate Professor of Painting/Printmaking and Director of Graduate Studies at the Yale School of Art Meleko Mokgosi ’07. Mokgosi returned to the College to give students insight into his creative process and wanted to “be as clear as possible about how [he] works,” he said in his talk.

Born in Francistown, Botswana, Mokgosi first came to the United States in 2003 to study studio art at the College. In the lecture, Mokgosi cited Max Beckmann — a German artist associated with the Expressionist movement — as his inspiration for how he thinks about his own art. As Mokgosi explained, Beckmann’s art combines “realism and allegory with mythmaking,” full of perplexing and seemingly disjointed elements.

In linguistic semiotics, signs are traditionally composed of both the signifier (the word itself) and the signified (the meaning attached to the word). However, Mokgosi explained that Beckmann subverts this concept in his art, which Mokgosi said is a tenet that grounds his own work. “Beckmann’s signs derive their meaning as much or more from the context, the specific roles they perform,” Mokgosi said in his talk. “In his paintings, there seems to be no hierarchy in terms of the meaning of any one aspect of the painting. The canvas acts as one plane that holds different signs whose meanings are interdependent. Everything on the canvas has meaning equally in relation to the human being.”

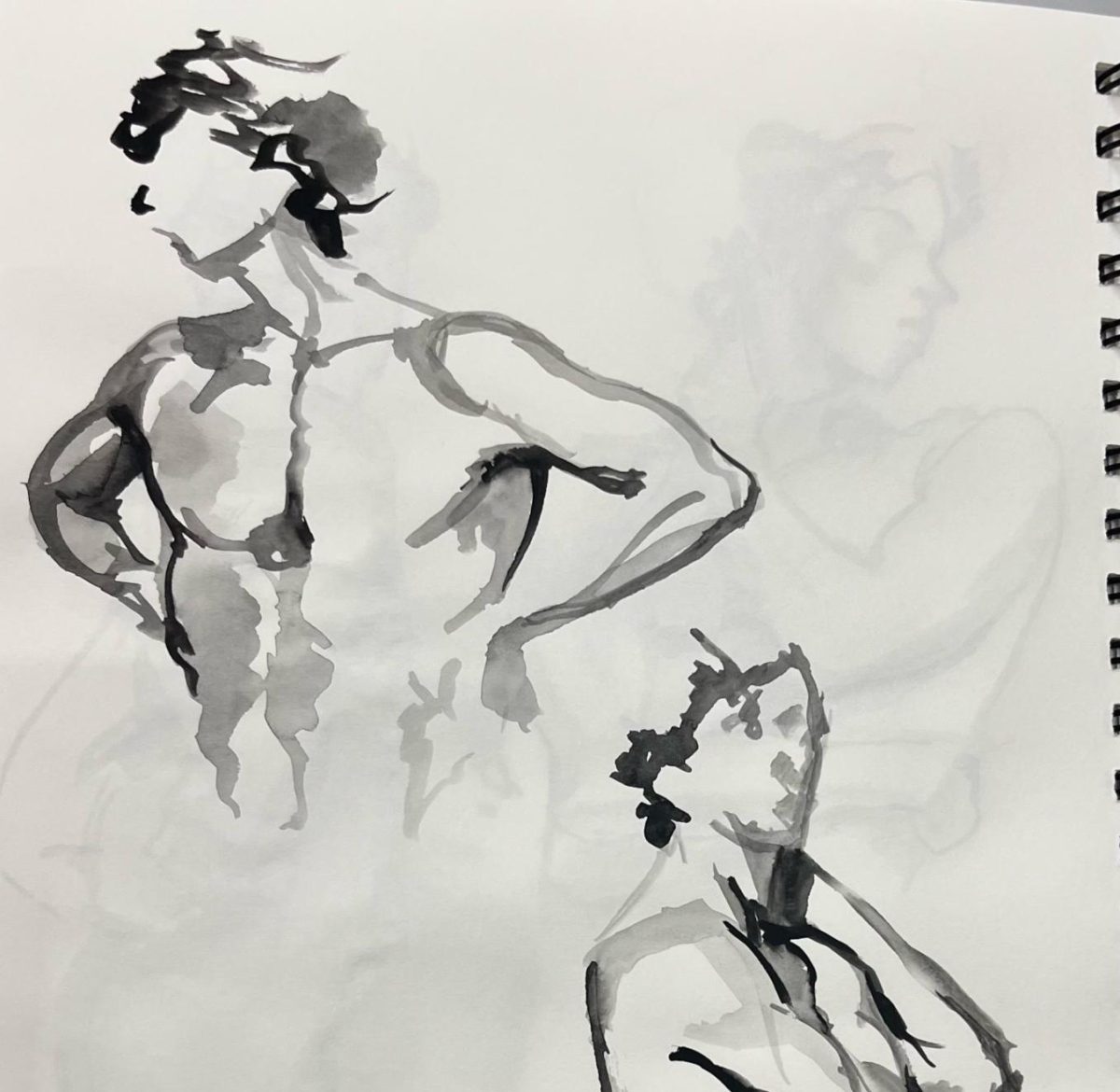

Mokgosi’s artistic and stylistic decisions are extensively organized. “My planning phase comes from this storyboarding technique where each pattern is laid out through line drawing, then scanned, then redone,” he said in the lecture. “Then I work by mapping out different brushstrokes, color systems, composition issues and so forth.” This process, he said, can take up to seven months. He called his approach to painting “reductive,” removing paint while it’s still wet to create dimension by subtraction rather than addition.

“I also do a lot of speed painting,” he joked. “That’s what happens if you have kids and teach full time.”

Mokgosi also said that metanarratives — “narratives about narratives” — guide the lens of his art. Metanarratives and their role in the creation of social structures are some of the themes of Mokgosi’s latest body of work “Spaces of Subjection,” an ongoing body of work that he started in 2020.

The project — which is broken up into different thematic subgroups — is expansive in size and interdisciplinary in scope. It is made up of annotated panels of text, small recreations of Beverly Jenkins’ romance novels, and massive paintings blending quotidian and surreal elements, contrasting colorful and black-and-white pieces. Mokgosi said that the idea of “subjection” is taken from Michel Foucault’s theories on subjects and power. “Subjection refines the relationship between the human and structural mechanisms by assisting in the process by which we become human,” he said. “We become human by being subordinated to power… To become part of the collective we are subjected to and we internalize norms so that we can be accepted into that community.”

“What I appreciate about this approach is that there isn’t a particular focus on identitarian issues or topics, which ordinarily narrow the scope of humanism,” Mokgosi added.

One subgroup, titled “Spaces of Subjection: Black Paintings,” contains a huge black-and-white oil canvas portraying a mystifying array of surreal elements: a street that turns into a beach, stray bony dogs, a lone baby sitting on the street, a billboard with a picture of a happy Black family next to an empty street vendor’s set-up, and a Coca-Cola ad with two smiling women in bikinis towering over the beach. By draining the color from the piece, Mokgosi simultaneously removes the concepts of time and space, creating an image that is reflective of the blurred lines between reality and imagination under the structures that delineate society.

“Part of what interested me about subject formation was the relationship to childhood and trying to reconcile how we’re socialized into the beings that we become,” Mokgosi said. In the subgroup “Spaces of Subjection: Zones of Nonbeing,” Mokgosi portrays a four year close-reading of Epaminondas and His Auntie, a children’s book about a caricature of a Black child who makes a series of humorous mistakes, published in 1911 by a white woman. The book is widely criticized for racial stereotyping, although it originally comes from Black oral tradition. Mokgosi’s annotations wrap around the edges of the book’s pages, displayed as large successive panels, untangling how the book represents some of the metanarratives that constitute society.

Mokgosi explained that watching soap operas as a child inspired his work, as their unique formation of time and space influenced his interpretation of those concepts within his art. “Spaces of Subjection, Imaging Imaginations” features an installation of eight large subsequent oil paintings, seven of which are in a row while the eighth sits above the second panel. The paintings consist of vibrant scenes that simultaneously pull the viewer in and out of reality — a person in a bed covered with balloons, a couple looking out of a window, a table covered with mannequin heads, and a group of men sitting on the floor in front of an empty winged golden throne. Paintings that could be individual pieces are turned into one by Mokgosi’s decision to hang them directly next to each other. “If you look at this, it looks like a narrative that doesn’t end,” he said of the installation. “If I told you I grew up watching The Young and the Restless [and] Santa Barbara, it makes sense.” These seemingly disjointed paintings work interconnectedly, much like the structure of convoluted decades-long soap operas.

Mokgosi also made these artistic choices to resist the consumption and perversion of Black art. “I’ve always tried to commit myself to the idea that I don’t want my projects to enter the market as a single commodity,” he said. This has led him to create pieces that “occupy a certain amount of space physically and institutionally.”

During the Q&A following the formal lecture, an audience member asked Mokgosi how he captures viewers’ attention, especially with artwork that includes lots of writing. In part, he said that he makes his pieces “big and perverse because people have the attention span of a goldfish.” However, he explained that he also expects a certain level of ethical viewing from the audience “to recognize my commitment to the subject.”