From inconvenient to beloved: a brief history of Mountain Day

October 26, 2022

One of the most prominent features of College lore is Mountain Day, the annual tradition where the president spontaneously cancels classes on one of the first three Fridays in October to encourage students to appreciate the natural beauty of the Berkshires. It’s plastered across the College’s social media pages, wooing starry-eyed high schoolers with its supposedly deep-rooted tradition. A dive into the archives, however, indicates that this cornerstone of College culture has been far from constant.

Although the exact origins of Mountain Day are murky, an Oct. 13, 1931, edition of the Record describes it as a “Williams tradition of more than 175 years,” which dates it back to the 1790s, shortly after the College’s founding. The earliest written reference to Mountain Day, however, can be found in the journal of Edward D. Griffin, president of the College from 1821 to 1836, who referenced a school holiday to “go upon the mountain” in 1827.

On July 15, 1854, The New York Times published an article titled “College Customs at Williams,” which detailed “Chip Day,” a spring holiday where students were expected to clean up wood chips on campus grounds that had accumulated from the College’s firewood piles over the winter. By 1796, students at the College reportedly “preferred to tax themselves to a small amount and delegate the work to others” and thus devised a fund to pay workers from the Town to clean for them as they took the day off to hike local trails.

Most historical sources believe that this tradition later evolved into Mountain Day, which, in the mid-19th century, took place over the summer term. “The various classes … ascend Greylock, the highest peak in the state, from which may be had a very fine view,” the Times wrote. “Frequently they pass the night there, and beds are made of leaves, in the old tower, bonfires are built, and they get through it quite comfortable.”

In 1857, Mark Hopkins, president of the College from 1836 to 1872, also instituted “Scenery Day” or “Bald Mountain Day” (“Bald Mountain” being the antiquated name for “Stony Ledge”) as a spontaneous autumn holiday for students to have “ample opportunity to enjoy the magnificent effect of the changing foliage,” according a Nov. 14, 1874 edition of The Williams Athenaeum. A 1909 edition of the Williams Alumni Review described the way that Thompson Memorial Chapel would awaken students with bells ringing to the tune of “The Mountains,” the College’s alma mater, early in the morning. The students would “emerge from the dormitories, clad in old clothes and sweaters … in a bustle of expectancy and preparation,” ready to disperse on expeditions to nearby peaks, including Mounts Greylock, Prospect, and Berlin.

At around the turn of the 20th century, the College eliminated the summer term Mountain Day, giving the name to what had previously been called Scenery Day instead.

Reginald D. Forbes, Class of 1911, praised his autumn Mountain Day experience in the May 1912-April 1913 edition of the Williams Literary Monthly. “The light is upon the face of the freshmen, and in their hearts has dawned that which sets Williams men apart from all other college men — the love of the hills,” he wrote. An Oct. 13, 1913, Record article recounted the adventures of that year’s Mountain Day participants, including a senior who came within 30 feet of what he believed to be a cow until “the outline against the sky revealed the presence of a black bear.”

However, the tradition experienced a sharp decline in popularity in the 1920s. Wyllis Wright, Class of 1925, described how students at the College would use the day off to visit local attractions, in addition to all-women’s colleges nearby. “[Mountain Day was] the period when half the college went to Smith [College], and the other half climbed mountains, and [soon] all the college went to Smith and Vassar [College],” he said, according to the Williams’ Special Collections Website. In 1957, the Record quoted Joe Richardson ’57, who expressed his disapproval of this trend but admitted, “Naturally, as in the ’20s, many would prefer the smell of gasoline and Matchabelli perfume to the clean mountain air.”

By 1931, Mountain Day attendance had become so dismally low that, when roughly 50 students appeared at festivities that year, an Oct. 13, 1931, Record article praised the turnout as “unprecedented.” The tradition’s fate took a turn for the worse in 1932 when the student body called for the elimination of Mountain Day as a school holiday, proposing the addition of an extra day to the College’s then-single-day Thanksgiving break in its place. On Oct. 4, 1932, the Record editorial board endorsed this movement, complaining that Mountain Day often conflicted with their fraternity rushing weeks and stating that the event “retains no vestige of its former self.” The editorial board concluded that “the Record hopes that this traditionless tradition be scrapped.”

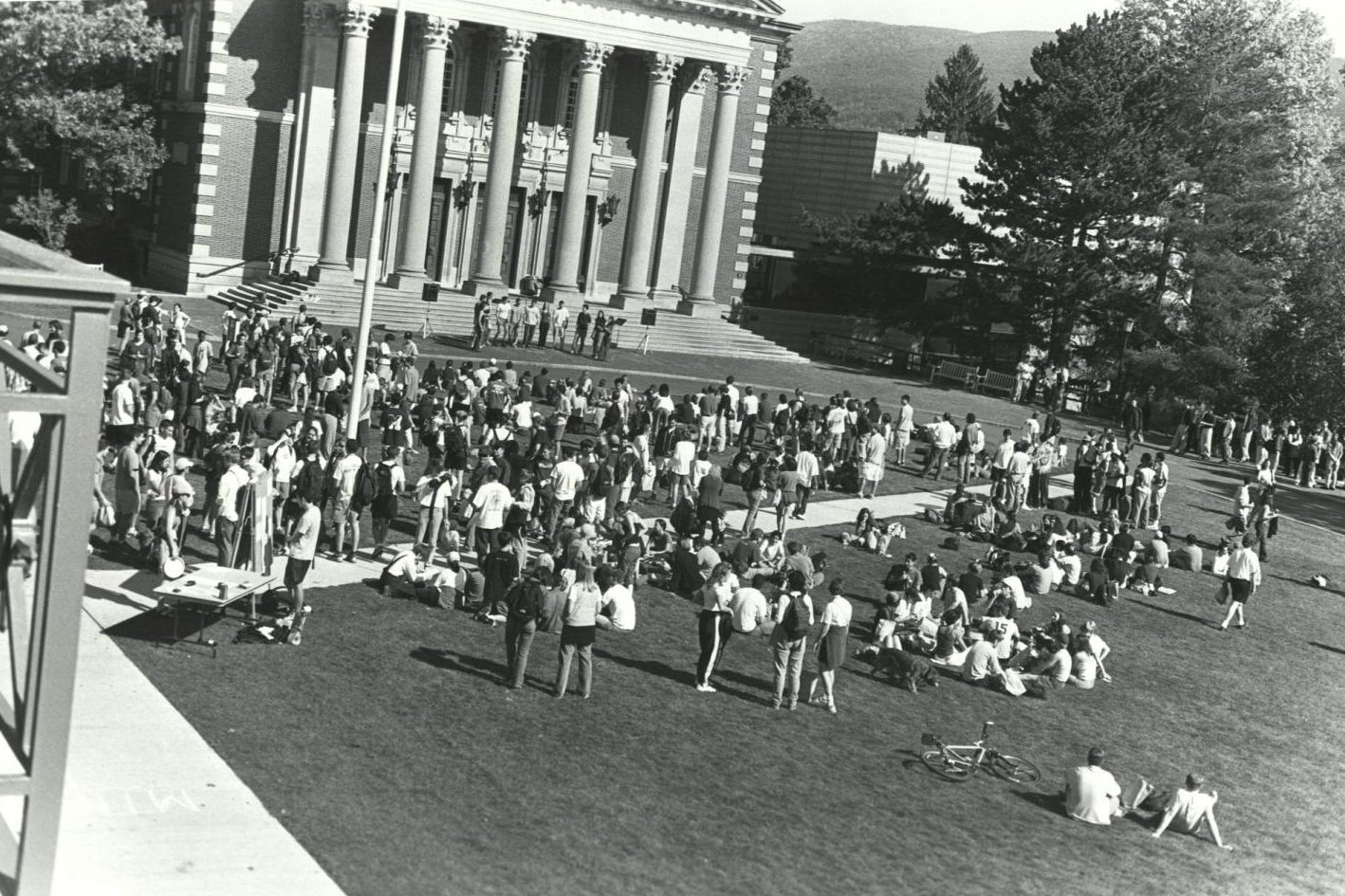

As a result of these protests, the College called a meeting, and over 700 “incensed” undergraduates attended to reaffirm their demands. Professor of Philosophy James B. Pratt, Class of 1898, took the stage in an attempt to defend the tradition. “Mountain Day is an essentially educative institution,” he argued. “It is part of every graduate’s liberal arts education… Should we let it go, it will be one more step toward factory-made Americans and factory-made colleges.”

His efforts were in vain, and on May 25, 1935, the College’s Committee on Administration voted to abolish the yearly event, wiping it from the academic calendar and collective memory of the College for decades to come.

For the next thirty years, the Williams Outing Club (WOC) planned various other communal events for the Mountain Day-less College, focusing its efforts on programming like the annual Winter Carnival. However, by the late 1950s and early 1960s, there was a revived interest in outdoor activity and thus renewed effort to bring back the forgone tradition.

“A revived Mountain Day would, we think, have a place at Williams…” Richardson wrote in his 1957 Record op-ed. “[This] would probably inspire people who at present never have the time or the energy, to get out on the trails and find out what they have been missing.”

On April 26, 1964, the Record board published an editorial titled “The Mountains” in support of reintroducing the event. “[Mountain Day] possesses very definite therapeutic values, it enhances the educational process, [and] — in short — it is good for the soul,” they wrote.

In response to growing demand, WOC held pre-planned “Mount Greylock Days,” which offered hikes and bike rides up to Stony Ledge (and in 1975, even featured a square dance, according to an essay written by Madeline King ’09 titled, “The Mountains! The Mountains!”), but the holiday was not formally recognized by the College.

When Jim Briggs became the Director of WOC in 1982, his explicit intention was to return Mountain Day to its former glory, but he was unsuccessful in fully convincing the administration to return to the spontaneous, class-canceling format of Mountain Days past. The administration instead relegated the event to a weekend day it also referred to as “Mountain Day.” Students often had alternative commitments, though, and Mountain Day turnout typically hovered around a mere 50 students.

It wasn’t until 1993 that the holiday returned to the College’s academic calendar, and not until 2000, after persistent effort by students and faculty alike, that it assumed the impromptu Friday format the College community is familiar with today.

This effort was spearheaded by Professor of Biology Heather Williams, who was committed to restoring an authentic Mountain Day for her students, and, conveniently for her, was the Chair of the Calendar and Scheduling Committee. “Little did anyone know of my secret agenda,” Williams said in an email to the Record. “Working with the committee, I put together a plan: Mountain Day would be a true Mountain Day, with classes called off and lots of people going up in the mountains to enjoy a beautiful day together.”

When Williams brought the motion to reinstate the tradition for a test trial of three years to the floor of a faculty meeting in the spring of 2000, she was met with opposition from many of her colleagues who deemed the canceling of classes as “unintellectual” and “encouraging students to play hooky.” Concerns over syllabus scheduling were repeatedly expressed, to which Williams countered, “We all have [doctorates] and should be able to cope with that.”

Ultimately, the faculty passed the motion by a slim margin, to which Williams credits “moving speeches” by emeritus Professor of Psychology Laurie Heatherington and then-co-President of the College Council Bert Leatherman ’00, who both outlined a need for “community-wide activities that brought everyone together in a positive context.” Director of WOC Scott Lewis also worked to convince the faculty of the practicality of such an endeavor.

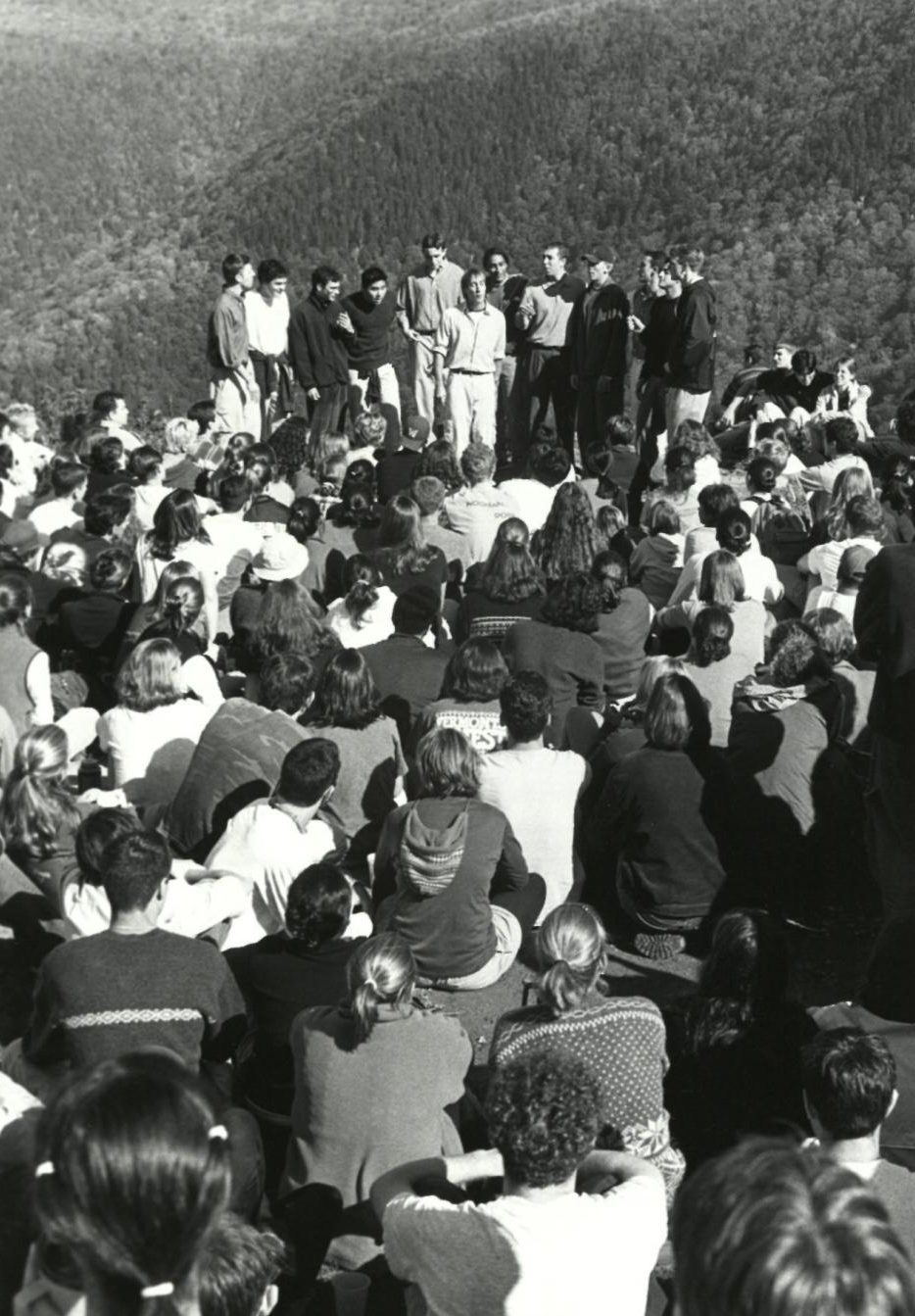

By the end of the three-year trial, Mountain Day had seen record turnout, with over 600 students making the trek to Stony Ledge each year, thus convincing the College that Mountain Day should be here to stay. The faculty later amended the motion to limit Mountain Day to one of the first three Fridays in October.

According to Lewis, hiking participation has dramatically increased since his first Mountain Day in the fall of 1992. Though WOC used to organize buses running to Stony Ledge for any student unwilling to climb Mount Greylock, Stony Ledge road closures around 2007 forced them to limit transport to those with verified accommodation needs, inadvertently increasing student participation on hikes.

With the new incarnation of Mountain Day came a slew of novel traditions, including already-obsolete activities such as climbing up the side of Chapin Hall (which was scrapped due to safety concerns) and the Eco Challenge, a decathlon-esque ritual where mixed-gender teams of four competed in events such as wilderness trivia, canoeing, bike-racing, and more, all culminating in a 3.5-mile race up to Stony Ledge.

But Mountain Day hasn’t existed without what Lewis lovingly calls “gremlins” along the way. A prime example is the Mountain Day of 2009, when forecasted snow on the last available Friday in October resulted in a Russian-themed “Siberian Mountain Day” featuring activities such as “Climb High, Climb Czar” rock-climbing and a “MosCow Naturalist Hike.” There was also the Mountain Day of 2020, where students could not gather on Stony Ledge due to COVID-19 restrictions and embarked on over 40 smaller hikes instead; or even the time when a hike leader accidentally led his group of 200 students up Mount Prospect instead of Stony Ledge, causing them to miss the festivities. (“I think they could hear the singing and smell the doughnuts though,” Lewis laughed.)

Through decades of trial and error, of ratification and repeal, Mountain Day currently stands as a giant within the Williams imagination, serving not only as an opportunity to look to nature, but also to ourselves — reminding us that this institution, its people, and its priorities are anything but unchanging.