‘The epitome of living history’: Looking back at the College’s first female faculty members

April 27, 2022

For the first several hundred years of its history, the College was an all-male institution. The College first allowed female students to enroll in courses following the Second World War and awarded its first degrees to female students in 1971. The process of hiring female faculty was a more piecemeal one, as a series of extraordinary women brought their talents to the College, from one partial class taught in 1935 to a near equally divided faculty today.

Emily Cleland was the first woman to teach at the College, filling in for her husband, Professor of Geology Dr. Herdman Cleland, after he died during a steam ship accident called the “mohawk disaster” in January of 1935, according to the Herdman Fitzgerald Cleland papers.

In its May 7, 1935 issue, the Record reported that Emily Cleland was “especially qualified to fill this post” given her bachelors degree from Smith College and Master of Arts degree from Columbia University. “She did a great deal of research work for Dr. [Herdman] Cleland in preparing for his book … and at the same time devoted many hours to scientific works in foreign languages,” the Record wrote.

It was over thirty years before the first female professor was granted tenure at the College. Associate Professor of Russian Doris deKeyserlingk received tenure in 1966, three years before the faculty voted in favor of granting women degrees and five years before the first group of female students graduated, according to a timeline of the College’s road to coeducation.

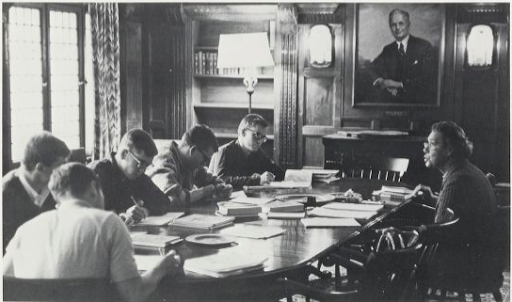

A professor of Russian and German, deKeyserlingk first came to the College in 1958 with the task of revitalizing the Russian department in light of the Cold War, bringing with her the vivid life experience of having lived through the Russian Revolution and two world wars. “[deKeyserlingk] charms her students with her cosmopolitan background,” the College’s 1959 yearbook said.

deKeyserlingk was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1903 and fled to Finland during the Russian Revolution. According to a Feb. 22, 1989 obituary in The Transcript, she spent the First World War making bandages at the Catherine Palace alongside members of the Russian aristocracy and moved to the United States in 1937 with her fiancé, a German man who had spoken out against Hitler. In 1946, she moved back to Germany to work as an interpreter in the Nuremberg trials, which she remembered as requiring a lot of psychological willpower. “You had to dissociate yourself entirely from the meaning of your work,” she said of the experience. “Those who couldn’t, couldn’t translate instantaneously and speak into the microphone… They gagged.” It was difficult to narrate the experiences of former Nazi officials without separating the work from the atrocities beign described, but deKeyserlingk was able to remain on the job for six years, returning to the United States in 1952.

By all accounts, deKeyserlingk was well-loved. “She was the epitome of living history,” wrote Bob Chambers ’68, who took her Russian 101 course his senior year after hearing about her life experiences. “[There] was [also] a side of Prof. deKeyserlingk that I loved to see — fun-loving, engaging, [and] empathetic.” She remained at the College until her retirement in 1971, announced in the June 6, 1971 issue of the Record.

deKeyserlingk’s time at the College was a period of transformation regarding the presence of women on campus. When she was granted tenure, there were only two other female faculty members: Professor of French Suzanne Savacool, a former French resistance fighter, and Nina Fersen, the director of the former Weston Language Center. Upon deKeyserlingk’s retirement, there were 18 female faculty members, making up 9 percent of the faculty, according to a Haverford-Bryn Mawr paper on the gender composition of liberal art college faculties.

At the time, many of the College’s peer institutions had also begun to admit female students and were slowly in the process of building faculty compositions that reflected their diversifying student body. A survey of northeastern liberal arts colleges in the same Haverford-Bryn Mawr paper found that only two of the colleges — Barnard and Wellesley, both historically women’s colleges — had faculties that were majority-female, with the rest having majority-male faculties.

Though she was one of the first women to broach the College’s previously all-male environment, deKeyserlingk brushed off her groundbreaking achievement. “I really don’t think it really makes any difference,” she said about becoming a tenured professor according to a Feb. 28, 1966 news release from the College. “There are men at women’s colleges, aren’t there?”