‘Pioneer Williams women’: Female students’ experiences studying at the College before coeducation

March 16, 2022

The College didn’t fully welcome women until 1971, when the institution officially became coed. Yet there’s a lesser-known history of women learning at the College long before coeducation was ever on the horizon — women who studied alongside male students but did not receive degrees until years or decades later, if they received a degree at all.

The College almost instituted coeducation nearly 100 years before women were actually admitted to the College. In 1871, Professor John Bascom instituted a committee (composed of five men) to discuss the possibility of coeducation. Ultimately, the motion to admit women failed three votes to two. According to a timeline of women at the College created by Special Collections Archivist Sylvia Brown, the majority reasoned that “Williams was established as a school for men, the College is not a university with the expanded course offerings women might desire, and public opinion regarding educating the sexes together was divided.”

In 1931, The Daily Reporter, a paper in White Plains, N.Y., announced that Beatrice Irene Wassercheid had been awarded the first degree ever given by the College to a woman. Wassercheid worked as a secretary to Dean of the College Harry Agard and successfully petitioned the Board of Trustees to allow her to complete her Master’s degree in American Literature at the College.

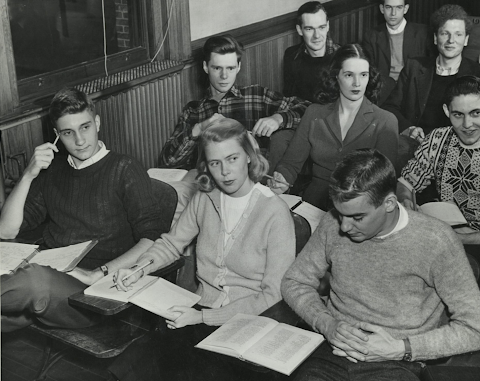

Additionally, many women who were wives of male students were allowed to take courses at the College. After World War II, hundreds of veterans returned to the College and brought their wives — referred to as “G.I. wives” — along with them. According to a Record article from Sept. 12, 1945, titled “Veterans, Wives Get Homes On Campus,” Greylock Hall as well as an inn on College property were to be extensively remodeled in order to house student veterans and their wives. Poker Flats was also built with the goal of housing veterans and their families.

In 1946, Life Magazine published an article on veterans on college campuses, which featured student experiences at Williams and the University of Wisconsin. The article referenced “Stan Fellner, 24, [who] returned to Williams last November as a junior after two and a half years as a Navy fighter pilot. He and his wife Shirley, a Smith College graduate, have been married six months, [and] live in Greylock hall along with eight other couples.” Some women attended classes with their husbands with “the majority going so far as to type out their husbands notes,” according to the Berkshire Evening Eagle in 1950.

The inclusion of women on campus and in the classroom was met with mixed reactions by the all-male student body. “Another aspect of Williams, which pleased some, haunted others, and frankly made others look aghast, was the aura of femininity invading our purple cloisters,” reads page 58 of the 1946 Gulielmansian, the College’s yearbook. “Veterans and wives had come to stay, and speculation ran rampant as to how soon Mrs. Baxter would open a day-nursery at which culture-hungry wives could leave Junior while they absorbed a Schuman lecture.”

Molly Asher was one female student who did not arrive at the College as a result of being married to a male Williams student. Asher grew up in Williamstown, the daughter of Ralph Asher, a former physics professor at the College, and eventually graduated from Williamstown High School. She graduated from the College in 1955, according to her obituary published in The Berkshire Eagle. She and her husband, a graduate of the College as well, moved to Kolkata, Indiana, where they lived for 12 years. Asher returned to Williamstown where she became the registrar of the Clark Art Institute, a position she held for many years.

In 1962, Linda Freeman Armour ’62 (then Strubel) — whose husband, Dick Strubel ’62, was a student at the College — completed the number of courses needed to graduate but did not receive a degree. She instead received a certificate of completion stating that “Linda Freeman Strubel has completed all the requirements for the Williams Bachelor of Arts degree. Under the rules of the College, however, she cannot be voted a diploma since Williams does not grant the B.A. degree in course to women.”

On Jan. 24, 1975, concurrent with the women’s rights movement and coeducation initiatives across the nation, then-Dean of the College Neil Grabois sent a letter to then-Chairman of the Trustee Committee on Degrees James Linen stating that four women who had completed all the requirements for a Bachelor of Arts degree from the College but had only received a certificate of completion were to be awarded retroactive B.A. degrees. These women were Katharine Mills Berry ’57, Elizabeth Stoddard Phillips ’61, Armour, and Judith Husband Kidd ’64.

Despite this triumph, Armour did not receive her physical diploma until 2007, two years before her death in 2009. A letter from April 30, 2007 to Armour from then-Director of Alumni Relations Wendy Hopkins reads, “It recently came to my attention that, although you completed the degree requirements at Williams in 1962 and were granted the B.A. degree in 1975, you never received your diploma. I am delighted to present it to you now with my warm congratulations and apologies that it was not sent to you long ago.”

In 2007, then-Director of the Williams College Oral History Project Charles Alberti ’50 and Robert Stegeman ’60 interviewed Berry, who was the first woman to be granted a retroactive degree from the College. Berry originally attended Vassar, which was then an all-women’s college, for two years as an American history and literature major. But after meeting Williams student Charlie Robert Berry ’57, whom she married after her sophomore year at Vassar, she decided to move to Williamstown.

Berry began taking classes at Bennington College, but after three days, she realized that she had already taken all the courses that Bennington offered in her majors at Vassar. “So I was really in a jam at that point, and Charlie said, ‘Let’s go see Dean [Robert] Brooks,’” Mills Berry said in the interview with Alberti and Stegeman. “So I went to see Dean Brooks, and he said, ‘Why don’t you come to Williams?’ So I did.”

Though Berry knew she would not be able to officially graduate or earn a degree from the College, she decided to finish her college education at Williams anyway. “Dean Brooks made [it] very clear that Williams conferred degrees upon men, but women who were wives of students, wives of professors, or people who lived in Williamstown had been allowed to take courses for credit ever since World War II when the returning veterans came,” she said. “So I could take all the courses I wanted for credit, but I did not expect to graduate.”

During her time as a “pioneer Williams woman” — a term then-Director of Alumni Relations R. Cragin Lewis ’41 used in a 1984 letter to Armour — Berry faced sexism from one professor in particular, who “refused to have a girl in his class,” she said.

The professor in question was an English professor who taught required courses for Berry’s American literature major, so she had to change her plans. Having taken a few economics classes at Vassar, Mills Berry decided to switch her major to economics, which she said ended up being a good choice, as she liked all of her economics professors.

After Berry’s long and winding road to completing a full college education, Brooks fought for her to receive some sort of recognition for her achievements. “So towards the end of the school year, Dean Brooks came to me and went to others in the administration and said, ‘I think we have to arrange for you to get a degree or to be recognized by Williams,’” Berry recalled. “He said, ‘You have gone to two of our country’s finest colleges: Vassar and Williams, and you’ve done very fine academic work, and no one’s going to give you a degree, and that is a reflection upon the educational system, not on you.’”

Berry was awarded the same certificate of completion as Armour and was told it held equal value to a Williams College degree. She received a retroactive diploma on May 15, 1975.

After her time at the College, Berry stayed connected to the community: She served as the co-chairman of the Class of 1957’s 25th Reunion and was the first woman to be nominated for a top Society of Alumni office. She served as the president of the Society of Alumni from 1988-90. Her daughter, Elizabeth Berry Gips ’82, and grandson, Benjamin Gips ’19 also attended the College. Benjamin Gips was one of the first students to be able to say his grandmother was a Williams graduate.

In 1971, Professor Fred Rudolph taught the College’s first course on women, entitled “The American Woman.” Now, the College’s student body is made up of approximately 50 percent women.

This article was updated on April 8, 2022 to include Molly Asher.