‘Like an adventure’: The beginnings of coeducation, 50 years ago

October 28, 2020

Fifty years ago, the Record announced the arrival of women as degree candidates with a typo.

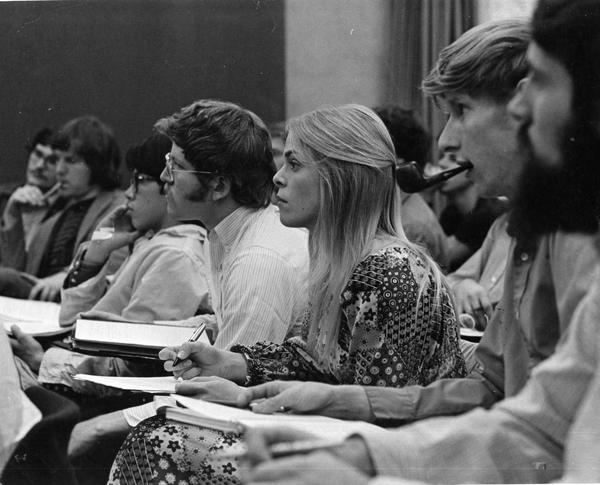

“98 coeds enchance college,” read the headline of a short Record article on Sept. 18, 1970.

The Record got the spelling right in the body of the article, which began: “This fall, Williams enhances the aesthetic value of the student body with the addition of 98 women.”

Half a century later, it is clear that women do more than “enhance” the student body — they make up 50 percent of it, according to data provided by the College (though these data do not include non-binary students).

But in the fall of 1970, when women first entered the College as full students, they were in the minority. It has been 50 years since the first 45 or so women students transferred to the College, along with 50 or so women exchange students, blazing the trail as a group of approximately 95 women in a school with about 1,250 men.

Path to coeducation

Williams had been an all-male institution since its founding in 1793. Although the College conferred degrees only upon men, after World War II, wives of students or professors were allowed to take courses for credit but could not graduate. One of these women, Katharine Berry, received a retroactive diploma in 1975 for having completed the College’s graduation requirements in 1957.

In April 1967, the Board of Trustees appointed a faculty-trustee committee called the Committee on Coordinate Education and Related Questions (CCE) to evaluate the possibility of coeducation. One option focused on establishing a coordinate college at Mount Hope, a system that would mirror that of Harvard University and Radcliffe College.

In the late 1960s, several factors made coeducation seem feasible and even necessary for the College. One was that the College had recently abolished fraternities, an all-male social structure that could have impeded a smooth transition to coeducation. Another was that peer colleges were becoming coed, with Yale and Princeton accepting women starting in the fall of 1969. Finally, the College wanted to increase the overall number of students for economic reasons.

In January of 1969, a subcommittee of the CCE produced an interim report on the possible impact of coeducation. The committee found the addition of female students would be “indispensable to the growth of a modern college and its community.”

“Women have fewer pressures toward vocationalism and professionalism placed upon them,” the committee wrote in its report. “Their presence and participation in campus life would be a liberating and creative force.” The report added that “women will tend to strengthen the enrollment in a number of departments that are presently undersubscribed.” (This prediction turned out to be untrue, according to Nancy J. McIntire, a former dean.)

In January 1969, 30 female exchange students arrived at the College from Vassar to study on campus for the spring semester. At the end of the program, the exchange students told the CCE that their “experience has been a very good one for all of us.”

Eighty-one percent of Williams students polled said they were in favor of coeducation, while 14.5 percent said they were against it, according to the Winter 1969 issue of The Williams Alumni Review. “Many students recorded in favor of coeducation, however, said they would prefer a nearby coordinate college without girls in classes at Williams,” the Review reported.

In the spring of 1969, the faculty and trustees unanimously voted to admit undergraduate women. That summer, the committee published its final report in the Review. “If Williams wishes to continue to attract first-rate students and faculty, the trend for the decades ahead point to a community in which women are present as students, faculty, and administrative officers in significant numbers,” the committee reported.

With the shift to coeducation, the trustees decided to expand the number of students at the College. “We would not subtract 100 boys to add 100 girls,” Director of Admission Frederick C. Copeland told The Berkshire Eagle in April 1972. “We will let the college grow in a gradual fashion to 1,800.”

In December 1969, nineteen women applied to join the College’s Class of 1971 as full undergraduate students. Five women, four of whom were already at the College as transfer or exchange students, received acceptance letters: Judy Allerhand (now Willis) ’71, Jane Gardner ’71, Gair Hemphill (now Crutcher) ’71, Joan Hertzberg ’71 and Ellen Josephson (now Vargyas) ’71. Two more joined the class later: Karen Mikus ’71 and Christy Shepard ’71.

“Although most girls enter the exchange program to be in a co-ed situation, this really isn’t coeducation, simply because there are so few girls here,” Vargyas, who attended Mount Holyoke College before transferring to Williams, wrote in the Review in the winter of 1970. “But at the same time we are helping to make it possible for others. I feel as if we’re in the vanguard of a significant movement in American education — it’s almost like an adventure.”

Deciding to transfer

Crutcher first got to know Williamstown as a Smith student visiting her then-boyfriend, a student at the College. “I was besotted with the campus,” she said, stressing the importance of “the effect of landscape on the human psyche.” She enrolled as an exchange student in her junior year and then became a full transfer student in the fall of 1970.

In addition to the seven women who joined the Class of 1971, dozens of women transferred to the sophomore and junior classes.

Wendy Wilkins Hopkins ’72 began college in the fall of 1968 at Connecticut College, one year before that institution switched to coeducation. “We were all thinking about where we really wanted to be, and many of my friends and I participated in opportunities at different all-male schools to see what it would be like to go to those schools,” Hopkins said. She participated in an exchange program that included a week at Dartmouth College, where, she said, the fraternities were hostile.

She arrived at Williams in the fall of 1970 already familiar with the campus, as her father and brother had attended. As a junior exchange student, she wanted to take a class on medieval architecture with Professor Whitney Stoddard.

“When I got to Williams, two things happened,” Hopkins said. “Before classes even started, I fell in love with the place and the town and I just felt — I felt like I was at home. It was wonderful. And the second thing I learned was that he wasn’t teaching the course I had wanted to take until second semester. So I started lobbying immediately, before classes even started, to see if I could transfer into Williams.”

Women’s residential and social life

The person primarily responsible for admitting women and responding to their needs once they arrived was McIntire, who started at the College as an assistant dean in August of 1970, working part-time in both the dean’s office and the admission office. McIntire recalled that some of her colleagues at the time would incorrectly refer to her as “dean of women.”

Before she arrived, McIntire said that the College had already made arrangements to add the services of two local gynecologists to the Health Center. It had also set space aside for a women’s locker room.

“The College had painted it pink and put in pink tiles, and I thought that really wasn’t so great,” McIntire said. “I suggested that maybe instead of making the walls pink, we could make the walls beige or white to offset the bright pink tiles.”

One of the biggest tasks facing McIntire and the other deans was that of housing. The College placed women either in suites in larger dorms like Prospect and Mark Hopkins Houses or in smaller houses like Doughty, Susan Hopkins and Lambert, which are now senior co-ops. Women were affiliated with larger, male-dominated houses for dining and socializing, though they did not live there.

“One of the mistakes, I think, that we made was dividing up the women in the small houses and assigning them to the men’s residential houses for dining purposes,” McIntire said. With women spread across campus, she explained, no one house had a critical mass of women.

McIntire also said that the College could have done a better job in engaging with and recruiting undergraduates of color. The first women to come to the College were, like the student body in general, mostly white — as were the professors. “The college was very far behind in focusing on faculty hiring, both for hiring faculty of women as well as faculty of color,” McIntire said.

In part because women were dispersed in different houses, and in part because the overwhelming majority of students were men, many women mostly made friends with men. Hopkins was close with her roommate, also a former Connecticut College student, but befriended few other women.

“I was not interested in getting a boyfriend,” she noted. “You know, I had classmates who married classmates. So there were romances going on. That just wasn’t part of my interest.”

Crutcher recalled befriending a “lovely, familial, fraternal fun group of men” — one of whom, Rick Crutcher ’71, she later married. The group went on adventures together, including raising a pig, rock-climbing by night (her hair got stuck in the rocks) and traveling to North Carolina for a fiddling convention.

“I think of how pleasant it was to be with such an intriguing and buoyant and adventurous and familial group of people,” she said. “It was as if I had fallen in with a family — a trustworthy and fun-loving family.”

Experiences of sexism

In her senior year at the College, Vargyas conducted a study of students’ views on coeducation. One question asked students to complete the sentence beginning “I feel that coeducation at Williams is…” Among male students, responses ranged from “good,” “essential” and “healthy” to “O.K.,” “poor” and, bizarrely, “rhinoceros.”

Hopkins said she never experienced sexism herself, but she had friends who did, including a roommate whose English professor was misogynistic.

“I was treated as a curiosity,” she said. “I was treated as somebody they wanted to find out about, get to know. There was never, in my personal experience — there was never hostility.”

Crutcher said she did not remember experiencing sexism while at the College. “I could have been in some, I don’t know, blissed-out bubble, and just not noticing that kind of thing,” she said. “Or maybe I was so overwhelming that people didn’t approach me. I don’t know.”

Russ Pulliam ’71, who as a sophomore wrote the Review article about attitudes toward coeducation, recalled that the general opinion among male students toward coeducation was favorable. He stressed that they were more preoccupied with issues like the Vietnam War than with resisting coeducation, adding, “I’m not sure it would have been a big controversy even without these national issues that really did attract attention all through my college years.” For his part, Pulliam said he enjoyed having serious conversations with women and getting to hear their different perspectives.

In comparison to some peer colleges, like Princeton, the College generally found alums to be supportive of coeducation. McIntire recalled that the alums she would meet as part of her duties as a dean were often pleased with the idea that their daughters could receive the same kind of education that they themselves had received. And McIntire and Hopkins both speculated that the alums who would have been most outraged about coeducation had already given up on the College once it abolished fraternities in the 1960s.

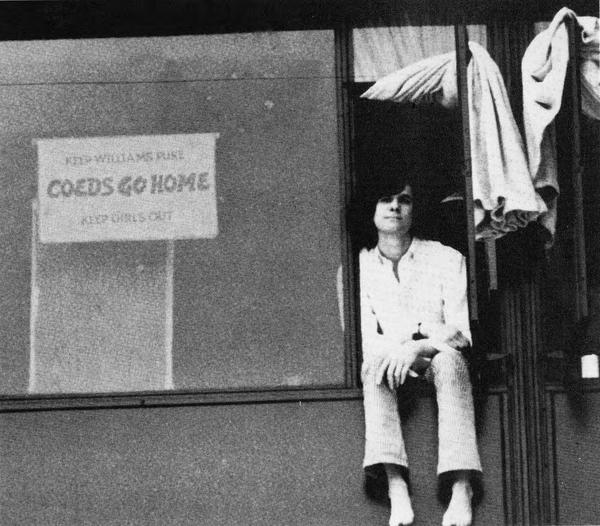

Still, the women did experience some sexism. It ranged from mild instances, like being asked in class to give “the woman’s perspective,” to the more extreme, like the occasional sign saying “Coeds go home,” according to McIntire.

“Most of the guys were just fine,” Vargyas recalled. “Some were idiots — which, you know, was probably no different from any other time.”

Taking advantage of the College’s opportunities

In a time before Title IX, the College had to contend with whether and how to provide athletic opportunities for the women. McIntire said that she and the athletic director discussed two different approaches towards athletics. One path meant waiting to see what female athletes preferred and then developing collegiate competition after that, while the other path (McIntire’s) meant assuming that women would want programs identical to the men’s. Although the issue wasn’t a major conflict, McIntire said the difference in ideas did delay the opportunity for women to compete athletically when they first arrived at the College.

“In the early ’70s, there wasn’t much competition,” McIntire said. “Several women spouses of faculty and staff did some coaching for women, and there was a small group of women who played basketball and had some competition with a few other colleges, but it wasn’t until after that women’s athletics really took off at Williams.”

Still, the women students participated in various activities, joining the Outing Club, writing for publications and conducting academic research. Hopkins sang in the choir, and her roommate joined the theater program after both students were encouraged to get involved, as the choral director wanted higher voices and theater groups needed female performers.

Female alums praised the many academic opportunities the College offered. Vargyas recalled enjoying her classes, noting that the grading was easier than at Mount Holyoke, from which she had transferred. (She said the male students assumed that Mount Holyoke was easier).

“I thought the courses were good, and I loved the Winter Study program, and took a fairly good range of classes,” she said. “I enjoyed it.”

In June 1971, seven female students graduated as members of the Class of 1971, with Hertzberg as class valedictorian. Although these were the first cohort of women to graduate, they would not be the last. Younger transfer students would graduate the following year, and the Class of 1975 — the first to have women enter as first-years — would arrive at the College in the fall of 1971.

Half a century later, Crutcher recalled her time at the College as “a sort of golden bubble of happiness.”

“I view that time of my life as Camelot or something,” she said. “A sort of brief shining moment that, when I think of it, my heart feels really happy.”

This article has been updated with more accurate numbers of women transfer and exchange students who arrived in the fall of 1970.