Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints presents a new facet of LeWitt

March 9, 2022

If there is one thing I know, it is that you either love Sol LeWitt or hate him. It is difficult to not have an opinion on LeWitt, who came into fame in the late 1960s and worked until he passed away in 2007, because his work opened a new paradigm. To many, he is a pioneer of conceptual art that redefined art production. To others, he is the epitome of what they dislike about fine art (cue the “I can make that too” argument). But fans and critics alike largely agree on one thing about his colorful, geometric work of bright lines and bands: LeWitt’s art is stoic, mathematical, and programmatic.

As MASS MoCA’s Sol LeWitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective acutely depicts, he was a master of creating sets of guidelines that dictate the work’s execution; he was an artist not because he put his brush on canvas but because he was a visionary that constructed blueprints. Consider, for instance, Wall Drawing #154: “A black outlined square with a red horizontal line from the midpoint of the left side toward the middle of the right side.” His concise instructions conjure the same image for all of us, regardless of the draftsperson, and blurs the line between idea and object. LeWitt seemed to agree with this understanding as he stated in an essay for Artforum: “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes the machine that makes the art.”

Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints, on display at the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) tells a different story. The exhibition, to those who knew LeWitt only through his wall drawings or geometric structures, shares a new facet of his work both in terms of medium and content. Over 200 lithographs, silkscreens, etchings, aquatints, woodcuts, and linocuts — “the most comprehensive presentation of the artist’s printmaking to date,” as the WCMA website boasts — successfully paint LeWitt as a multidimensional figure with a much wider oeuvre than commonly appreciated.

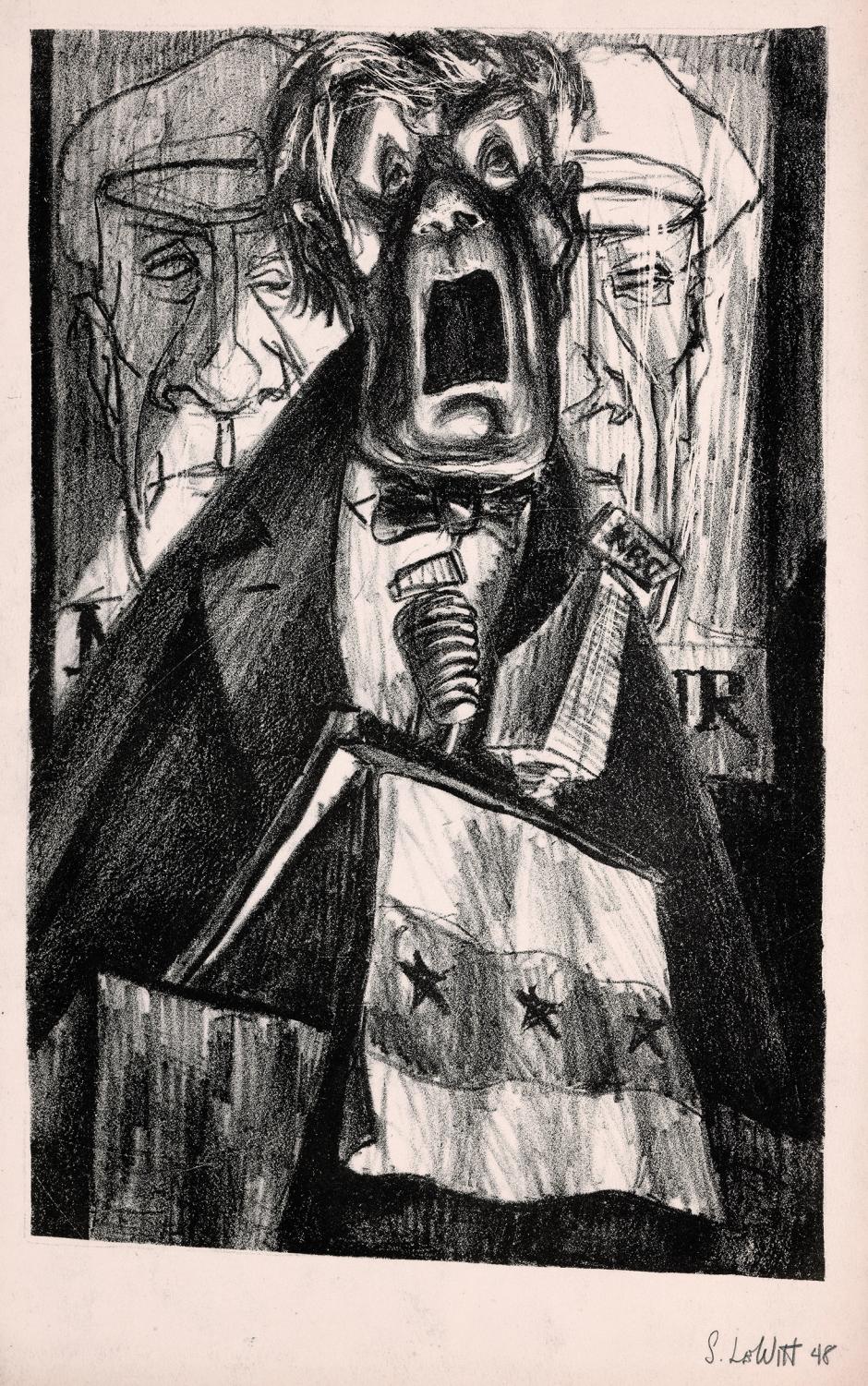

The exhibition begins with a set of lithographs that most art lovers would not imagine to be LeWitt’s works. Among the first salon-style display of a dozen prints, his iconic vibrant colors and abstract designs are nowhere to be found. The prints are a selection from his works from 1947 to 1954, largely during and after his BFA program at Syracuse University. LeWitt had not discovered his distinct artistic vision at this point, but it is interesting to take a look at what he experimented with in the formative years of his career. Untitled (Politician) — a lithograph made in 1948 that coincidentally yet uncannily resembles the 45th President of the United States — displays LeWitt’s interest in social and political engagement. Other lithographs that seem to be abstracted landscapes hint at a gradual evolution into the linear visual language that he used later on in his career.

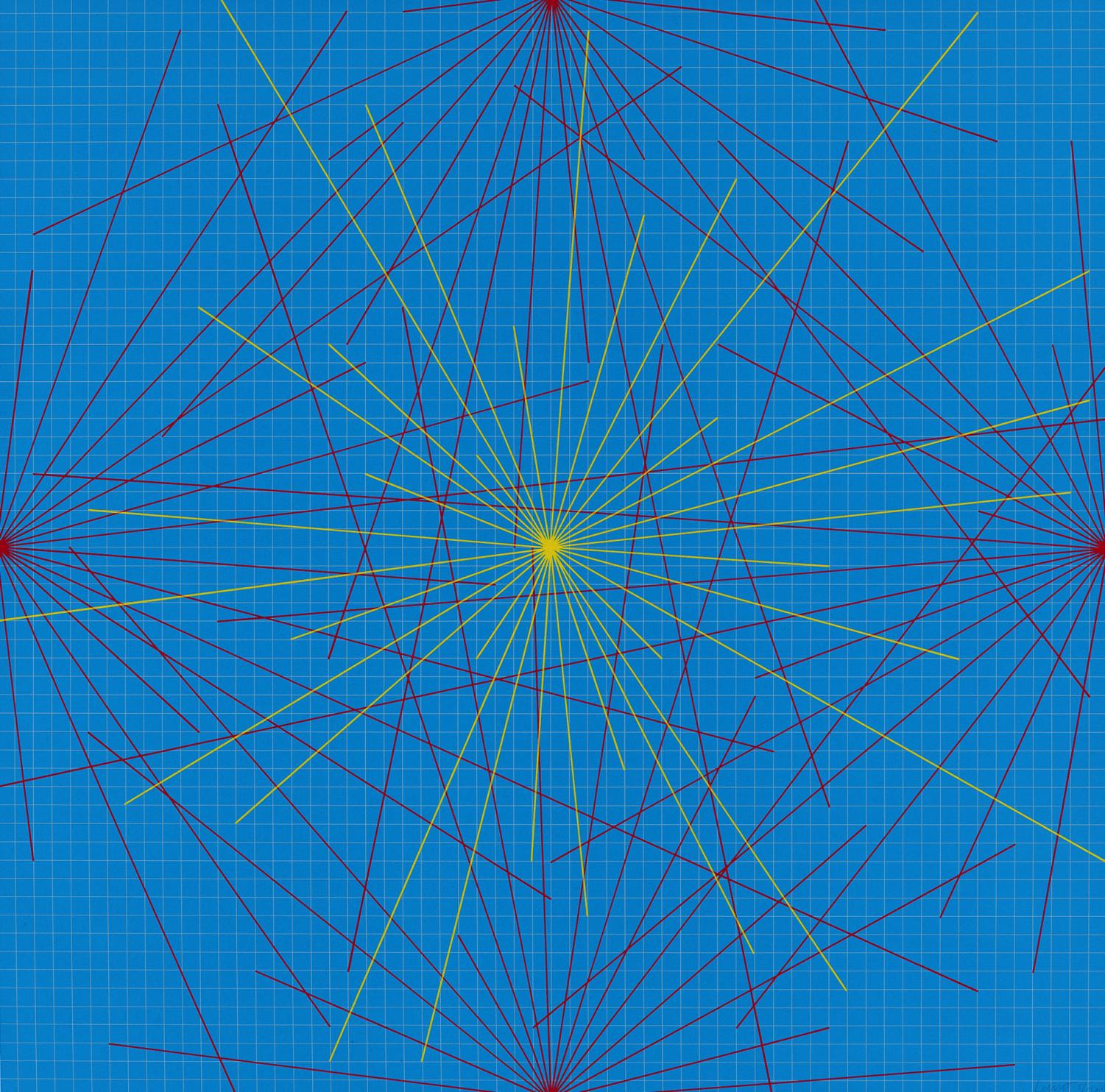

After 1954, LeWitt focused more on wall drawings and sculpture (or “structures,” as he liked to call them) until he returned to printmaking in 1970. As a pioneer of conceptual art, he appreciated printmaking’s unique capacity to recreate art from a predetermined concept: quite literally a mechanical process that employs the idea to make the art. His early works, condensed under the section “Lines, Arcs, Circles, and Grids,” chronicle the construction of his unique visual vocabulary. Series like Lines in Color on Color to Points on a Grid are in direct dialogue with some of LeWitt’s other famous works like Wall Drawing #289, exploring lines on a grid as building blocks of an image, presenting a viewing experience akin to topographical maps. He created simple and rigid visual rules and explored all their mathematical combinations in search of a surprising resulting image.

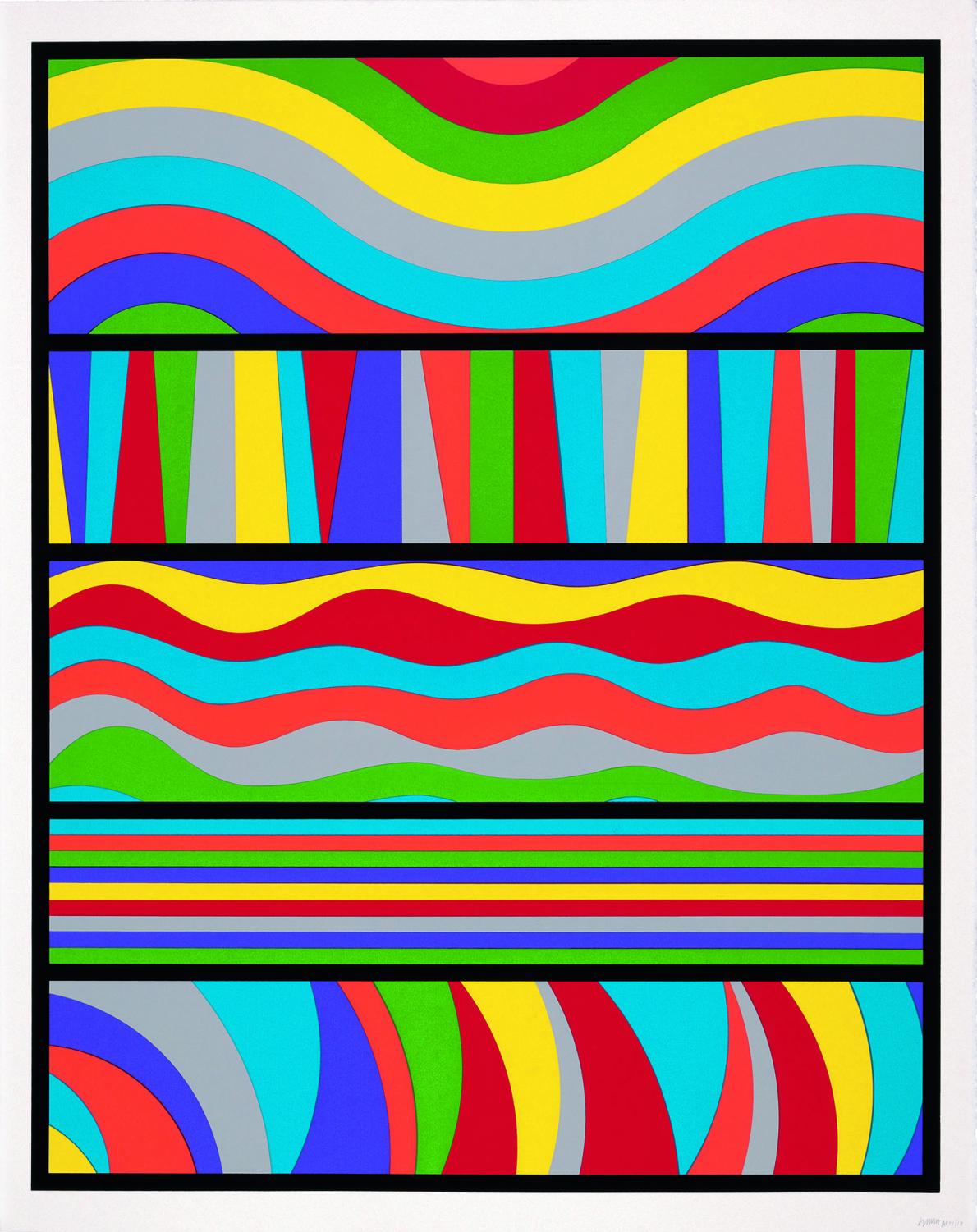

Strict Beauty moves on to chronicle the expansive growth of his career and his embracement of new artistic vocabulary like the use of bands and color. A standout work is Lincoln Center Print, a silkscreen limited edition print promoting the annual Mostly Mozart Festival at the Lincoln Center. The screenprint invokes the image of sheet music, brightly colored bands oscillating through five stacked rectangular frames, like how notes surf through staff lines in a music score. LeWitt generates a rhythm that bounces between order and disorder, between rigid rules and creative compositions.

While all the works featured in the first half of the exhibition are stunning, they do not introduce a new LeWitt. The part of him we get to see is the part we already love about him (or at least, the part that I already love). The highlights of the exhibition are when LeWitt contradicts himself, deviating from the rigid visual rules that his work follows to display moments of emotion, personal history, and the complexity and inconsistency of the human experience.

One remarkable example is Shul Print (Six-Pointed Star), a linocut that puts LeWitt’s Jewish identity at the forefront — a surprising move for someone who was neither particularly religious nor employed much religious symbolism in his works. As the exhibition catalog explains, the print’s title — Shul, a Yiddish word for school or synagogue — “specifically refers to the artist’s local synagogue, Congregation Beth Shalom Rodfe Zedek in Chester, Conn.” The synagogue is the only building that LeWitt helped design, including the general architecture and diverse elements like its skylight or the aron kodesh. Not only is Shul Print an extension of LeWitt’s visual investigation into the star shape’s flexibility, I cannot help but read it as an attempt to connect to a once stigmatized and oppressed part of his identity.

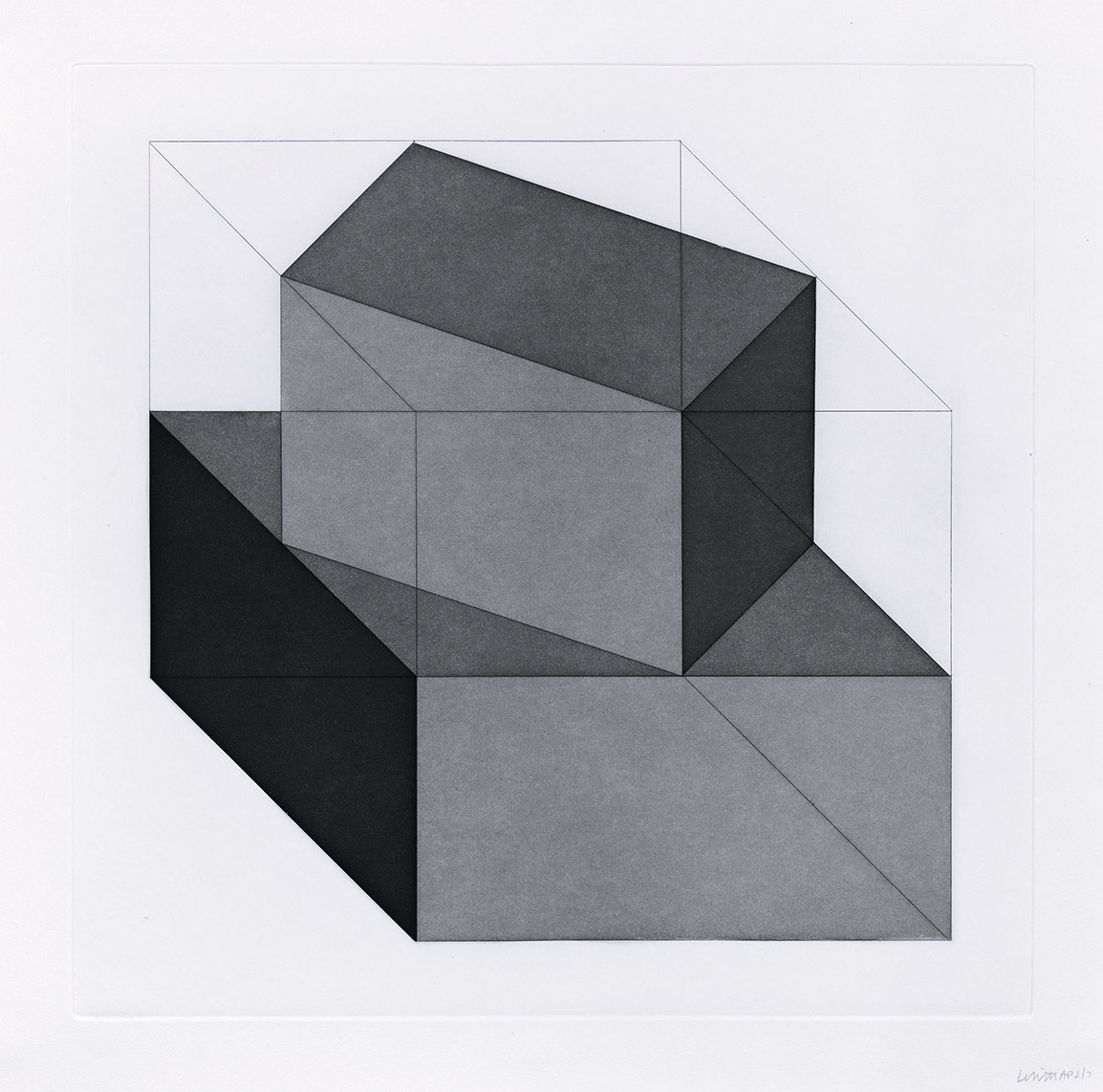

Contradictions, or perhaps evolutions, also arise in works such as Forms Derived from a Cube. This etching and aquatint set of twenty-four prints presents, with no particular method or order, different three-dimensional shapes that reside within a cube. A meticulous combination of a limited number of tools is nowhere to be found in this series and is instead replaced by LeWitt’s whims. There is no limit to the number of forms one can imagine, nor is there a programmatic order in how they progress from one to another. The series operates not under a predetermined logic but under LeWitt’s creative vision.

At times, LeWitt produces works that no one would even dare attribute to him. One of the final works to be seen in the first gallery, Complex Forms, is a series of aquatints that have a relaxed, watercolor-like touch rather than his iconic linear bands. Colors seep into each other, infringing their boundaries, highlighting the presence of LeWitt’s hand. Instead of straight lines, solid colors, and a systematic logic, it almost feels like the series portrays an abstract, amorphous creature rather than a pattern.

The second gallery congregates more prints under the title “Wavy, Curvy, Loopy Doopy, and in All Directions.” I spent a lot of time in front of Whirls and Twirls (Color), tracing the colorful bands that fold into themselves. This möbius strip-like path that curves left and right, bending like a race track with corners and chicanes, seems to have a traceable direction. Yet when my eyes chased them, the seemingly evident path evaporated. LeWitt constantly jumped between order and disorder, trying to find a comprehensible and pleasant rhythm on the canvas.

This is by no means an easy task. The world is full of disorder and confusion, with inexplicable twists and turns that constantly shake things up. But perhaps what LeWitt pursued with his art, with his ideas and his directions, is a chance to perceive beauty in a language that we speak. Using lines, arcs, circles, colors, and shapes — all basic visual vocabulary that we comprehend clearly — he constructed complex and alluring images that are at once programmed and uncontained. It is a process we all struggle through in life, trying to make sense of a world that constantly evades our comprehension. LeWitt’s brilliant prints at Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints, like Robert Frost once attributed to poetry, are “a momentary stay against confusion.”

Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints is on display at the WCMA through June 11, 2022.