Review: WCMA asks itself questions via Sweaty Concepts exhibit

September 29, 2021

2020 marked the 50th anniversary of co-education at the College, the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment’s ratification, and the 99th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. These stories that were overshadowed by the pandemic — and as such are often forgotten — are at the forefront of the Sweaty Concepts exhibition at the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA). The exhibition reminds us that the struggle to “make one’s space fully theirs” is not a concept unique to the pandemic.

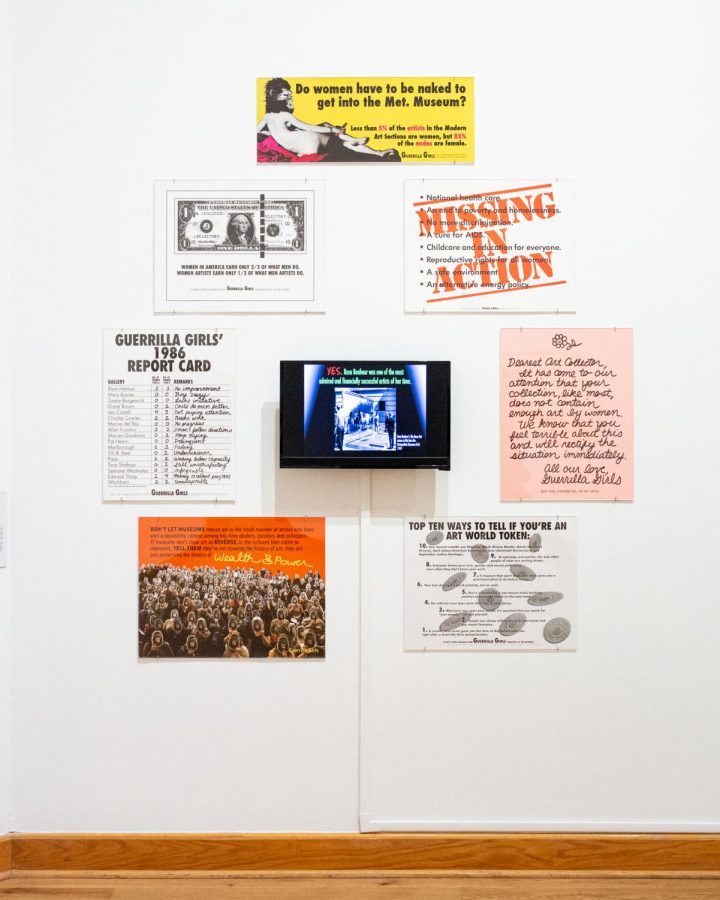

Sweaty Concepts shines a light on those who have fought for their right just to “be,” describing “experiences across gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and ability, that involve making a place for oneself where it does not already exist,” as WCMA’s website explains. The exhibition borrows its name from feminist scholar and writer Sara Ahmed’s notion of a “sweaty concept”: a concept “that comes out of a description of a body that is not at home in the world.” The exhibition, drawn from WCMA’s collection, is not united through form or method of expression — visitors see works ranging from Nayland Blake’s graphite sketches on paper to Jenny Holzer’s iconic LED installations — but are united by spirit. Sweaty Concepts is a chronicle of struggles over the last half century to fight for space as a woman, a Black person, an East Asian immigrant, a sexual minority, an Indigenous person, a religious minority, and a disabled person.

Visitors to the exhibition first encounter Kerry Stewart’s This Girl Bends (1996), a fiberglass sculpture emanating its presence from the center of the gallery. The gravity-defying girl is at once realistic and uncannily unnatural. She embodies the uncomfortable nature of breaking the glass ceiling while highlighting the superhuman strength required to reach for, and ultimately obtain, equality.

Another standout work is Nancy Spero’s Androgynous Bomb & Victims (1966), the gouache and ink on paper depicting an androgynous figure fiercely exerting what seems to be streams symbolizing war and sexual violence. Immediately noticeable are the creases and wrinkles of the paper that Spero used — a deliberate choice to veer away from the male-dominated medium of oil on canvas. She responds to at once the Vietnam War and to the perpetual violence of the patriarchy, connecting the image of bombs exploding to ejaculation. The painting is an aggressive, emotional rejection of violence and asks the viewer to notice the similarities (and at times the congruence) between the patriarchy and war.

May Stevens echoes this rejection of the patriarchy and war in telling a tale of individual struggle and oppression in Big Daddy Paper Doll (1970). Steven places the portrait of her “patriotic” father in the context of paper dolls to respond to the patriarchy and the then-ongoing Vietnam War. A phallic paper doll with the clothes of a soldier, a police officer, a butcher, and an executioner represent the violent patriarchy and imperialism of the times, yet is stripped of its power and is recontextualized as part of a traditionally “feminine” paper doll set.

Patty Chang’s DVD single-channel video Fountain (1999) richly coincides with the feminism in Spero and Stevens’s work. Chang explores the intersectional nature of oppression she faces as an East Asian woman living in the United States. The work clearly calls to the imagery of Narcissus and presents the struggle of an image to become whole again. By addressing beauty standards, the male gaze, and representations of Asian women, Fountain outlines the process of looking into one’s identity from the uncomfortable and often violent gaze of other people.

Still other works seem more relevant in the current day. Zoe Leonard’s I want a president (1992, reprinted 2018) is a deeply personal relay of desire for representation, pointing out the seemingly impenetrable barriers for LGBTQ+ and economically disadvantaged people to influence the political decision-making process. After the historic U.S. presidential elections of 2016 and 2020, Leonard makes us think how much we have changed and how far we are from the world outlined in I want a president. The words, printed on onion-skin paper and installed behind a transparent plate, seem as if they are written on the wall. Perhaps this resonates with the desire for representation to be set into the foundations of our society, like how the text seems to be engraved into the fundamental structure of the building.

Through humor, anger, bitter sadness, or nihilism, the artists pave the way to challenging societal power dynamics that perpetuate systemic oppression. They are no longer asking questions like “Do I belong?” “Can I take a seat?” or “Could you please respect me?” They make statements, rejecting the forces that kept them out, proudly declaring their right to be here and make the space fully theirs. In this way, Sweaty Concepts is indeed a platform for historically underrepresented voices to make a stand.

The questions asked in the exhibit could be asked of WCMA itself and its legacy and future. As a museum inside a predominantly white liberal arts college heavily influenced by a history of colonialism and enslaved labor, WCMA must be particularly vigilant of its relationship with oppressive systems. The museum’s possession of Assyrian reliefs, donated for controversially colonialist missionary work and its comparatively thin “African,” “Amerindian,” and “Eastern” collections both raise questions to be answered for WCMA to be inclusive to all.

However, Sweaty Concepts undeniably brings to the surface discussions about fighting oppression. One hopes it is a declaration — corroborated by WCMA’s attempts to reflect on its history through exhibitions like Remixing the Hall, which reflect on the College’s relationship with colonialism and slavery — by the museum about its vision of becoming a home for all the different voices at the College, where everyone will not only “be” but also thrive.