A special time with Special Collections: Meeting Dürer’s ‘Apocalypse’

May 5, 2021

Encountering a piece of art previously only seen in a low-quality course packet is one thing; that piece of art being the five-century-old iconic woodcut print Apocalypse by Albrecht Dürer is another. This past week, I had the opportunity to take a look at Dürer’s magnificent prints, along with many other astonishing pieces in the College’s Special Collections.

My Special Collections journey started in my art history course on Western art from the Renaissance to the present. We were looking into various printmaking techniques when Professor of Art History Catherine Howe briefly mentioned the College’s expansive collection. “Actually, the College has one of the original Apocalypse books that Dürer made,” she said. “Isn’t that crazy?”

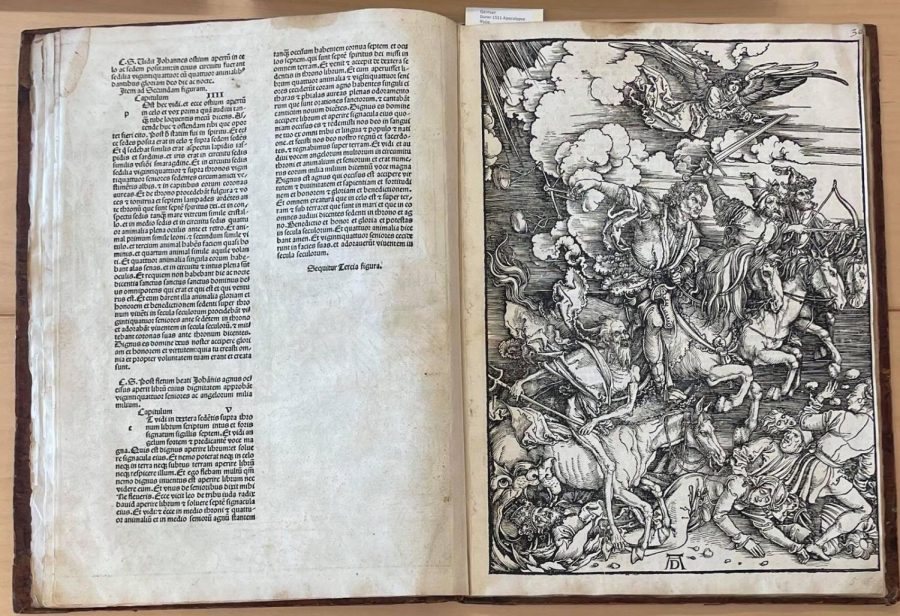

The Apocalypse with Pictures is a book of Dürer’s dramatic illustrations of scenes from the Book of Revelation, and the book initiated his printmaking stardom across Europe. It was printed and published in 1498 — when the Y2K-esque myths of a possible Last Judgment in the year 1500 were taking over Europe — and was the definition of a sensation. Since then, this print has traveled more than 500 years and across the Atlantic Ocean to be in Williamstown. My professor was right; it indeed was crazy. I needed to find a way to see this woodcut in person.

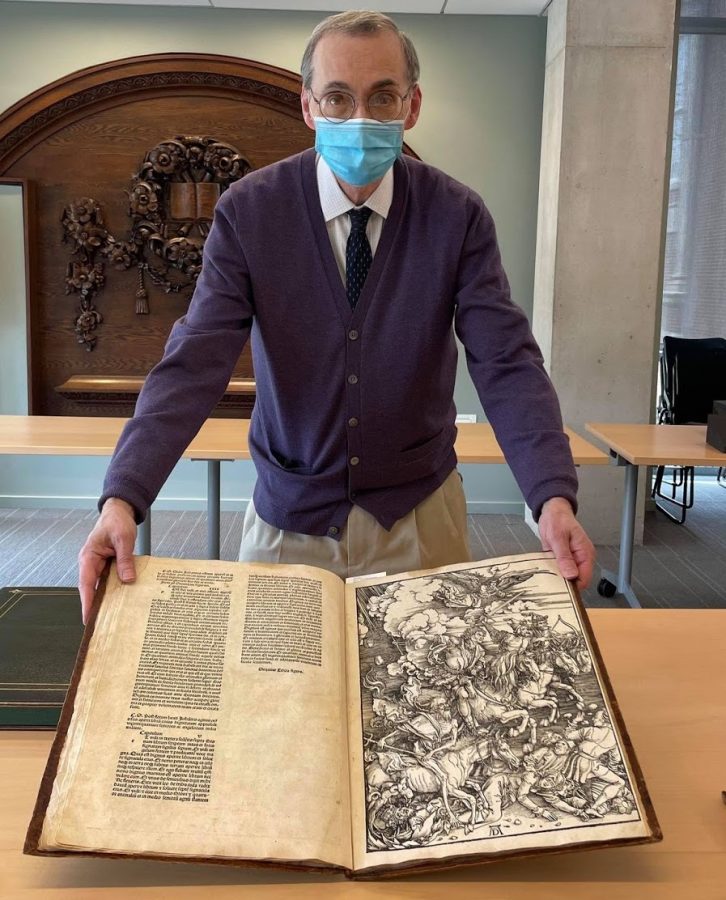

Getting to see it was easier than I expected. I visited the College’s Special Collections website, scheduled an appointment, and was told to come to the fourth floor of the library, where I met Chapin Librarian Wayne Hammond. He had a three-story metal book truck, filled with books and boxes that even from a distance seemed old and important. Hammond invited me into the reading room of the library and laid the books on a table. As his fingers slid through the pages, visibly old but in pristine condition, he explained the history behind these books in detail.

The Apocalypse is one of the many books made by Dürer that the library owns. “The Apocalypse, of course, is very well-known and we happen to have a nice copy of it,” Hammond said. “In most places, as an undergraduate, you wouldn’t be able to get close to it. It would be behind glass, or you would see it from a distance, or you would see it in reproductions.” But, with care and precaution, students at the College can request to look at these collections up close, like they would any other book.

Looking at the woodcuts up close was an overwhelming experience. The fine lines pointed to Dürer’s experience as a goldsmith, where he engraved laborious details into sheets of metal. Dürer’s linear form and meticulous attention to detail were evident on the paper. All the stories that I had learned in class were coming alive in front of me, whether it be Dürer’s method of creating space and depth through varying distances between horizontal lines, his iconic monogram signature on the book’s spine, or the scrupulous perspective and contours. Dürer was no longer just a PowerPoint slide. His artwork had been fully engraved in my memory, just like the images he carved into woodblocks.

Hammond put into words what was going on in my mind at the moment. “If you want to look at art, you want to look at the original,” he said.

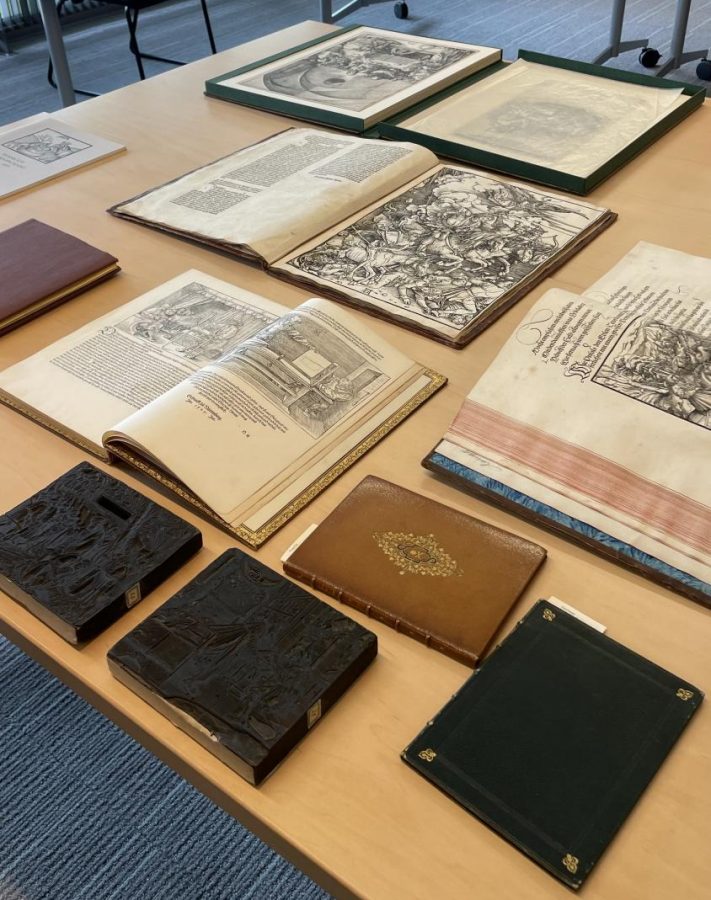

He proceeded to introduce me to other collections, such as the Four Books of Measurement (Dürer’s work on perspective, proportion, and measuring) or the Great Passion and the Small Passion (Dürer’s series of woodcuts on Biblical themes and the Passion of Christ). Displayed together were works by Lucas Cranach the Elder or Hans Holbein the Younger, all flaunting the beauty of masterful German woodcut art. I was stunned when Hammond brought out nine of Hans Weiditz’s actual woodblocks created for Cicero’s work on old age.

Hammond always accompanied these prized collections with valuable details. “The hole here, you can see, is a mortise for them to put type in,” he said, pointing to the rectangular slit in the middle of the woodblock. “It would print at the same time with metal print on the page. These are, as far as we know, the only ones of these to survive.”

I spent an hour in that room, appreciating all the precious collections that lay less than a foot away from me. When I mentioned that I never thought I could get to see such works of art up close, Hammond reminded me that the Chapin Library is a major resource not only for artwork but also for literary sources, manuscripts, books, photographs, and other pieces of the past. Other rare documents held in the Special Collection range from archives of Daniel Chester French, the American sculptor who created the Lincoln Memorial, to copies of the founding documents of the United States.

This caught me by surprise because I never knew these prized collections were even at Williams, let alone that they could be accessed by students at any time. I asked if students often visit the library to look at these collections. “I’ve been here since 1976 and I can tell you that when I came, we almost saw no one throughout the year,” Hammond said. “We thought, ‘Well, what would happen if we look at the course catalog, see what’s being taught, write to the faculty, and suggest what we could do for them?’ Immediately, by reaching out, we got a lot of interest.”

Hammond was more than excited to tell me that anyone and everyone should be visiting the library. “We had a student who wanted to read Milton’s Paradise Lost, but in an early edition,” he said.“So he came in, sat down, time after time, and read from the first illustrated edition.” His stories convinced me that my visit to see the woodcuts was a great choice. Not only was I able to appreciate amazing artworks that I never thought I would be able to see, but I was also motivated to visit the Chapin Library and explore their vast collections of rare books and manuscripts.

Although Hammond was excited that more people were appreciating the collections at the College, he also mentioned that a lot of students continue to miss out on opportunities to use this amazing resource. “I’ve found over these many years that many students are not aware of what we have, or that it can be looked at,” he said. “But these [collections] are here for your use. You don’t have to be writing a paper or taking a course.”