Erin Shirreff provides insight into her Remainders Exhibition at the Clark

March 17, 2021

The proliferation of mobile devices and the internet ushered in a wind of change for the art world. Now visitors at art museums and galleries around the world can snapshot, record, and access artwork at the convenience of their fingertips. Canadian photographer and sculptor Erin Shirreff asks a question about this seemingly-effortless process that none of us commonly raise: What remains of art when it is translated through different mediums?

The Clark Art Institute hosted a virtual conversation with Shirreff on March 10. Shirreff, along with Associate Curator of Contemporary Projects Robert Wiesenberger, discussed the general ideas behind her works along with her current exhibition at the Clark, Remainders. The free, year-long exhibition that operates in between the boundaries of photography, sculpture, and video, runs from Jan. 16, 2021, to Jan. 2, 2022, and consists of installations scattered throughout the Clark’s public spaces.

Shirreff, born in 1975 in British Columbia, currently works out of Montreal. She trained as a sculptor and earned her MFA at the Yale School of Art. Shirreff has been under the spotlight recently as the subject of solo shows at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, N.Y. Her current works “explore the relationship between objects and their representations, and the mythmaking behind art history,” Wiesenberger explained.

The question Shirreff wants to ask through her work seems to be one that would resonate in the minds of art historians and art lovers alike: What happens to a sculpture, a painting, a photograph, or an installation once it becomes a grainy picture on a textbook? In other words, as the Clark website puts it, “what is left of the original experience of an artwork once it has entered the historical record, and what traces of an artist’s labor might still be legible after the fact”?

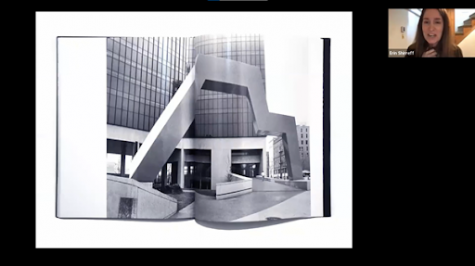

Shirreff began the webinar by explaining the Fig. series on display at the Clark reading room. The term “fig.” is short for figures, the conventional term used to denote illustrations in text. The series consists of photographs of objects Shirreff made in her studio with pigmented plaster, each standing 15-17 inches tall. They are photographed on a seamless backdrop, which Shirreff explains was employed to “render the scale a bit ambiguous.” Shirreff then used the computer to reorganize the photos into a composite form of two halves from separate pictures that join each other at the center seam.

Looking at the frame from up close, one can notice how the center seam is designed to look like the crease in between pages of a book. The effect is amplified as the photos themselves are folded inside the frame, adding a three-dimensional touch to the artwork’s metaphor.

“The idea is that they refer to a book spread that has been detached from its signature in the bookbinding process,” Shirreff said. “It’s presenting information that is sort of knowingly incomplete.”

Shirreff mentioned that she has been producing the Fig. series for a long time, based on a sequence of questions she started asking herself after graduate school. “I was asking these basic, fundamental questions about what I had just devoted all this time to: what it meant to be an artist and make art, what actually I was looking for in terms of creating an aesthetic encounter with the viewer, and what did I actually think was going to happen when a viewer was looking at art,” she said.

What started the spark was the artwork of Tony Smith (a pioneer in American Minimalist sculpture). She explained that encountering Smith’s installations — such as the New Piece, a black tetrahedral object placed on a park — made her feel a deficiency in having a meaningful experience with the art, stemming from the fact that she was not a contemporary of the artist. Simultaneously, Shirreff noticed that her “experience with the pictures [of sculptures] was so much more mysterious and generative and absorbing.”

Based on these experiences, she started the Fig. series to delve deeper into understanding what legacy art leaves behind. Shirreff explained how she was “taken with this question of how these objects are carried forward in time and our experience of them is now completely dependent on how much we allow ourselves to imaginatively project into these images.” When a primary experience with art from the past is absent, how does the lens of secondary text and information change the way that art is appreciated?

Shirreff took her set of ideas into space to see what the ideas of the series would look like as an object. Using foam core boards, she translated what used to be two halves from two different photos into a self-standing, three-dimensional piece. She granted the object a scale she imagined it to be, unlike the ambiguous sizes of the framed artworks. The foam core boards were then transferred to a foundry and rendered in bronze.

She expressed her appreciation for the moments of confusion that sprout from the sculpture going from foam to bronze. “From a distance, I think it masquerades as this a conventional abstract sculpture,” Shirreff said. “I feel like any sort of the authority of the conventional art object or the conventional art sculpture — the bronziness of the art historical weight of the material and the authority of the weight — really gets undermined because you see the true jankiness of its origin and its character.” She emphasized the seams of the sculpture, where a cast of the glue gun replaces the conventional line of metal weld, as a detail that carries the object’s spirit.

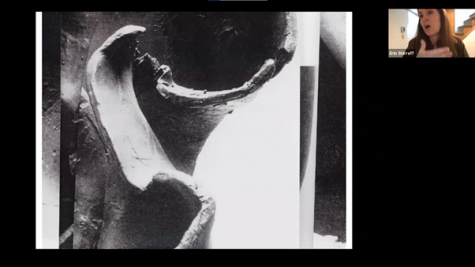

Next, Shirreff explained the two large-format dye sublimation prints that are on view in the Lower Clark Center. She encountered a book with a photograph of abstract expressionist artist David Slivka’s Laocoön, and was immediately struck by the luscious tactility apparent on the page.

“That’s a credit to the artist, but of course the photographer of the object, who is a well-known figure in the New York scene as an artist and photographer himself, Rudy Burckhardt,” she explained. For her piece, that image was scanned, applied to 4-by-8-foot sheets of aluminum with dye sublimation (a process that fuses images with metal), fragmented into intricate patterns, and then organized by an informal composition of leaning the pieces on the wall.

The title of the piece is Bronze (Slivka, Burckhardt, Busch, Laocoön). One might first notice the string of names that contributed to the photograph ending up on the book. But instead, Shirreff highlighted the title Bronze: “That, in the end, was what I was most curious about. How does the materiality of this object translate through the offset printing, through the photograph?”

The bronze indeed goes on a lengthy journey, ricocheting through different forms of being a sculpture, a paper illustration, a jpeg., aluminum sheets, then finally culminating in the deep 6-inch frame that Shirreff uses to make the work “seem encased in glass,” to borrow her description.

“I’m just thinking broadly about all the veils between you and the original objects in these books,” Shirreff said. “I’m interested in understanding how these things contour our understandings.”

The other dye-sub — she calls this type of work dye-subs because of the dye-sublimation technique it uses — Four-color café terrace (Caro, –––––, Moorehouse, Matisse) reflects her focus on the modification of art as it transfers through mediums. Her work is based on a photograph of Caro’s sculpture, taken by an unknown photographer (hence the “–––––”), that based itself on Matisse’s painting. “I was interested in this long historical lineage of artist looking at artist, technology looking at technology, and all the translations embedded in this object,” Shirreff said.

The final artwork she discussed was a looping video that was on view at the Clark. The video, called Still, consists of still images of the objects used in the Fig. photographs knit into a 39-minute loop. Much like her other work, the plaster objects are placed in an informal composition and carefully tracked by a camera as if it were filming an unending landscape. Graphite-colored objects that live in ambiguity — some feel like abstract shapes and forms while some seem familiar — slowly enter the screen and take turns fading into the background.

“None of the videos for me are about sitting and watching them,” Shirreff said. “They’re not narrative films; for me, that connects them to my interest in sculptural presence. You don’t assign a beginning and end to a sculpture. You go and you spend as long as you want with it.”

In response to a question asking if her work is suggesting viewers to subordinate the optical way of seeing to a more emotive perspective, Shirreff underscored how her artwork is supposed to be a visual encounter. “For me, before I even knew what an artist was, the most meaningful moments for me came through staring at my ceiling or something and have all of these other things happen in my mind,” she said. “For me, it always comes through looking.”