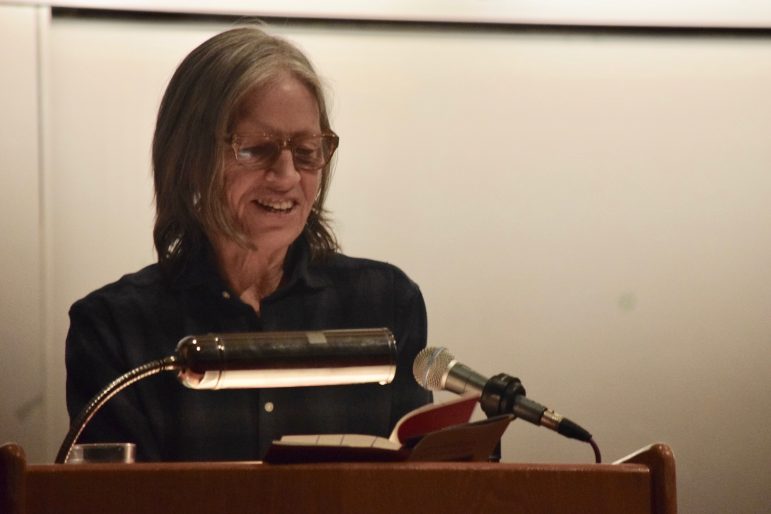

“I guess I’m an art writer and poet tonight,” deadpanned Eileen Myles, before breaking into a wide grin for a packed house in Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall last Thursday. They threw back their shoulders, chuckled and dove into their reading.

Myles has written more than 20 volumes of poetry, fiction and nonfiction. They have received dozens of literary prizes, including the Guggenheim Fellowship. The glowing response from their shelves’ worth of work, which includes quotable lines such as, “I am always hungry / & wanting to have / sex. This is a fact,” precedes Myles. But despite the widespread critical and viral acclaim, Myles was grounded and nonchalant Thursday night, musing on the profundities of writing. They were also willing, however, to “discredit it all,” having famously said in a Publishers Weekly interview, “The words don’t matter. Fuck the words.”

Myles opened with a recent essay written to accompany a series of exhibitions featuring the late artist Donald Judd’s paintings. Myles remarked on their own experiences living and loving in Marfa, Texas, the small town that was put on the map by Judd’s large-scale art installations in the untouched West Texas desert. Marfa, as Myles described it, was “deeply steeped in the religion” of Judd, a prominent American artist known for his rigorous work in questioning and recapturing minimalism as an art form. Myles’ email-formatted essay examined the triangulated relationships between the town, the artist and the writer themself, in a thoughtfully crafted narrative marked by quippy breaks and hairpin turns. “I think of the paintings as orange,” Myles read, “but only two are.”

From there, Myles followed with several poems from their most recent book of poetry, Evolution. This book captured Myles’ ongoing interest in writing the everyday into their work. In the titular poem, “Evolution,” they observe, “I’m / using this pen / on a purple notebook / set up on the / angle of my / thighs.” They then take a turn toward the reflective without pause, reading, “My thighs. / I’ve had you since / I was a kid. / I’ve known you for so / long. Even when / you betrayed / me in the bathtub / one night when / you were rabbits / but that’s cause / I was going / crazy.” After a beat, they pivot the thought toward the reader, catching a loneliness that feels all too familiar with their question, “Is it crazy / to be the / citizen who’s / only partially / here. Like / kissing while / your eyes / anxiously are surveying / the room.” With their abbreviated lines punctuated by short bursts of emotion, their reading rang true. As Alex Jen ’19, who brought Myles to campus and introduced them, put it, “[Myles] makes the familiar glisten again.”

Myles observes the mundane elements of day-to-day life from all angles, retracing these elements’ lines into their own lines of verse. They read with a fast-paced clip, shuffling through sheet after sheet of printed poetry, casting the pages aside the moment they finished. While Myles kept a casual delivery and rarely lingered, they were not flippant; their free-wheeling presentation matched the style of the poems themselves. Their bright tone of voice mirrored the visuals in their writing. “I can see / their blue / ladder / from here,” Myles read in their poem, “For My Friend.” “A man / has written / a book / about many / deaths / or many / things to do after. / Read it / read it / they say / but what / comes after / is a small / idea.”

Myles writes with queerness, sexuality and gender in mind as well. While the content of Myles’ work is multivalent and intentionally difficult to pin down, they frequently drew portraits of love – its presence, its absence, its shape in all forms – in the selections they read that night. In “Lucky Kittens” for instance, Myles read, “A world without mothers is a world without meat.” And in my personal favorite of the night, a provocative poem titled “Mary Queen of Scots,” they read, “Solaris / is the / interior / of my sexual / fantasies / I’m part / plant / eaten / by movies / for years / the veal / of snow / curves / as she drags / her pile / of trash / on the train / this is / any / butter / the lightly / screaming / train & / I’m excited / to see / you.”

Discussing their roles of both poet and essayist, Myles spoke about their relationship with writing. They expressed that the two roles often overlap, since they engage with the same creative process, regardless of the product. “They don’t feel different to me,” they said. “Writing is art. Writing is visual art.”

They further expanded upon how their self-identifications relate to their artistry. “I am choice, and I am style,” Myles explained, “but I am not content.” In this vein, Myles closed out the night with a longer poem titled “Sweet Heart.” “One / sleeps on what / they mean / and arises on the decided / side and that’s / the hope,” Myles read. “An entire / room is opened / by particular feelings / that say you’re / on the edge / of the space / and then you / wait to watch / it grow.”

This was Myles at their finest – easygoing laughter and dusty jeans, unassuming flannels and a keen eye for detail, acerbic language and edgy thought. They held themselves with ease, constantly interrupting their own reading to make note of where they were or what they were thinking when they penned the lines that held us audience members captive. One minute, they joked about pronouncing Marfa as “Mah-fa,” recalling their own Bostonian roots, and the next, they were comparing the “sonic nets” of an urban sprawl like New York City against the cicadas of Marfa, Texas. They were stream of consciousness without self-consciousness. They were effortless.