How exhilarating it would be to stand at the edge of a cliff, wind whistling around you, with the terrifying thought in your mind that the glorious view in front of you could easily be your last. After all, you’d only need to make one tiny movement to plunge to your death.

The 19th century Swiss painter Alexandre Calame believed this kind of experience, which engages the individual at once with nature’s beauty and immense danger, can reach a divine pitch. He even named what he saw as the spiritual height of this intersection between reverence for nature and fear of it – calling the sensation “the Sublime.”

The subject of the Clark Art Institute’s Extreme Nature!, which opened on Saturday and will run until Feb. 3, 2019, is the 19th century’s large-scale version of the Sublime pursuit – that is, its mass fixation on the mysteries of nature and its simultaneous staggering capacity for destruction.

In its own rather sensationalist way, Western popular culture in Calame’s time approximated the idea of the Sublime through channels like mass media, literature and tourism. Oftentimes, incidents stemming from recent industrialization would cause fires and floods in cities across the United States and Europe, and a rapidly growing newspaper industry was ever more equipped to cover these tragedies and any other natural disaster that would horrify and fascinate readers. Science fiction, like Jules Verne’s 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, allowed consumers to experience the drama of nature in their imaginations – and increasingly popular destinations like Niagara Falls enabled them to experience it in person.

Scientific journals also became popular during the 19th century and served to bring cutting-edge scientific thought to the public, as well as to artists. “New scientific journals challenged readers to contemplate nature’s shifting boundaries, but they also inspired artists to consider nature’s extremes in their art,” curator Michael Hartman, a Ph.D. student at the University of Delaware, said in a talk at the Clark on Sunday. “The public looked to artists as they sought visual documentation, confirmation or disavowal of the latest scientific theories and discoveries, while also looking for images of nature’s fury unleashed.”

In this vein, every image in Extreme Nature! depicts a natural phenomenon, whether it’s a meteor shower, a mythological depiction of the missing link in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution or statuesque angels falling through a canyon with geologically accurate rock striations. And this variety among the artworks is in part what defines the show, as it allows viewers to consider the 19th century’s attitude towards natural catastrophes from different angles.

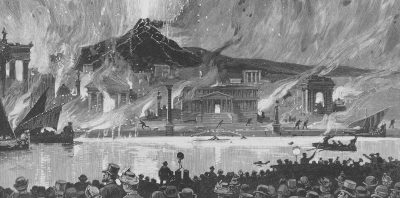

Some of the most powerful of these angles are provided by images published in popular magazines. Particularly notable is Charles Graham’s wood engraving entitled “Fireworks at Manhattan Beach – ‘The Last Days of Pompeii.’” Published in Harper’s Weekly in 1885, it epitomizes the bizarre stance towards nature in the pop culture of this age. The majority of the image seems to depict the ancient eruption of Italy’s Mount Vesuvius; we see a steep mountain exploding onto Roman-looking buildings below it. But in the foreground, a crowd of spectators decked out with a photographer and a band gives the eruption away as fake. As it turns out, the image that at first seemed to portray a famous natural disaster in fact depicts nothing more than a fireworks show in New York City, N.Y.

One could say that a huge party on Manhattan Beach centered around the recreation of a natural disaster conveys the essence of the 19th century’s cultural embrace of the Sublime. By drawing on the beautiful horror of nature to fuel a rollicking social event, the revelers in the image make use of nature’s ability to elevate human experience in the same way that the Sublime does. But advances in both science and journalism since the 19th century have left people today with a very different attitude towards these catastrophes. No longer mystified by their origins and constantly updated on their occurrences, people now tend to feel nothing but sorrow and, increasingly, contrition towards natural disasters. Extreme Nature!, in providing the 19th century contrast to today’s prevailing perspective on nature’s extremes, invites viewers to consider how the two perspectives might relate to each other. We’ll never stop trying to figure out how to exist on this blue ball of Earth, but art can give us the tools to start.