Rachel Levin/Executive Editor.

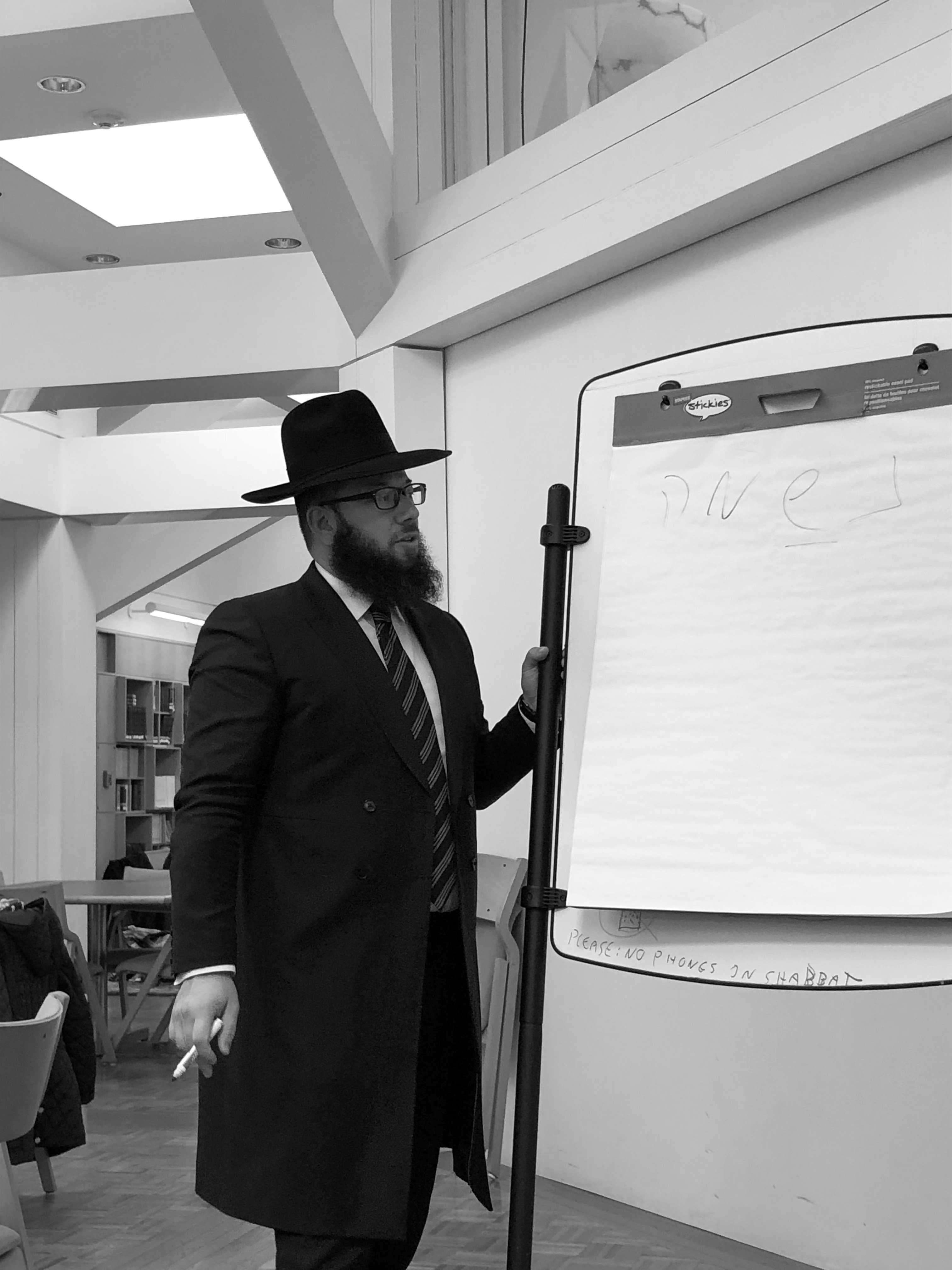

Last Thursday, Rabbi Mike Moskowitz, a rabbi at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (CBST) in Manhattan, spoke to a group gathered for lunch in the Jewish Religious Center. During the talk, titled “Trans Inclusivity and Yes on 3,” Moskowitz spoke about the ways in which Judaism can become more gender inclusive. This event was supported by Congregation Beth Israel in North Adams, Knesset Israel in Pittsfield and the Williams College Jewish Association.

The conversation began with a discussion of the misleading wording for Question 3 on the Massachusetts November ballot. Voting “yes” would maintain anti-discrimination policies for trans people while voting “no” would repeal these protections. This is what brought Moskowitz to Massachusetts, and the topic served as an important backdrop for the conversation that followed.

“I only started thinking about gender about three years ago, when someone in my family said to me, ‘I’m not a girl, I’m a boy,’” Moskowitz began. “And having since obsessively thought about gender, I can tell you honestly that I’ve reached what I think is a very evolved position of know-ing that I just don’t know.” Moskowitz’s journey with exploring gender in Judaism continued while he was a rabbi at Columbia, until he was fired for publicly taking a stance supporting trans Jewish students. This led to his involvement in broader social justice movements and his arrest for civil disobedience while fighting against the repeal of DACA in January. It was actually through this arrest that he got his present job at CBST, allowing him to participate in advocacy work publicly with institutional support.

After speaking about his background, he dove into Jewish texts and the Hebrew language to find ways in which Judaism supports all genders. “Who was the first person to transition in the Hebrew bible?” he asked the group. Confused faces stared back at him. “Adam,” he said. “Adam is created as one person, with the different genders, because the verse speaks about [Adam] in the plural.” It is from Adam that the binaries, male and female, were created, Moskowitz said.

Moskowitz also discussed the biblical story of Noah, who builds an ark to escape the flood that destroys humanity. “I think that Noah’s ark is a wonderful framing and modeling of a failed allyship,” he said, pun intended. Noah saves himself, his family and some animals, but “he is not at all concerned with what is happening in the world around him,” Moskowitz said. According to Moskowitz’s interpretation, to be an ally is to not just save or care about oneself, but to also be in tune with what is happening in the surrounding world, and if it is bad, to do something about it.

Moskowitz also discussed the ways in which one needs to be careful when being an ally. “I think it’s important not to valorize allyship,” Moskowitz said. “Allyships exist because the world is broken. If people could see the most pronounced identity of any human being as being created in the image of the divine, and we didn’t dehumanize people, and we didn’t subjugate and oppress then there wouldn’t be a need [for allyship] because everyone would be respected and seen for who they are.” This was a theme that carried throughout Moskowitz’s talk. Moskowitz recognized that he is an ally because the world needs him to be, but if the world was an accept-ing place and did not need him to be an ally, he would be happy with that.

The second half of his talk delved deeper into how to define gender and considered how a divine being can or cannot be gendered. The talk raised the question, where does gender lie in the divine? Moskowitz argued that gender may lie in a person’s soul. “If gender does exist on a soul level,” he said, “and we have all of the different pieces of all of the different souls in all of the different blends, it might provide a new kind of portal into having conversations about the kind of spiritual fluidity that I think we all have.”

Moskowitz also pointed out that much of gender construction in Judaism was created by straight, white, cisgender male rabbis, and thus was not created by anyone who may be marginalized. There are still many rabbis who believe in traditional gender roles within Judaism, but on the other end, there are also rabbis who have not drawn any lines regarding gender.

“I think it’s important for cis[gender] men to use the word ‘identify,’” Moskowitz said. “I think it’s im-portant for cis[gender] people to use the word ‘identify.’ I think it’s important for married people to use the word ‘partner.’ I think it’s important for people who present as cis[gender], whatever that might look like, to talk about, ‘my pronouns are.’” Moskowitz argued that this would normalize these terms and actions in a way that could elevate those who had been marginalized.

Throughout his talk, Moskowitz emphasized that this was his interpretation of Judaism and Jewish texts, and that he is still curious and still expanding his understanding, highlighting the importance of always being open and willing to listen.