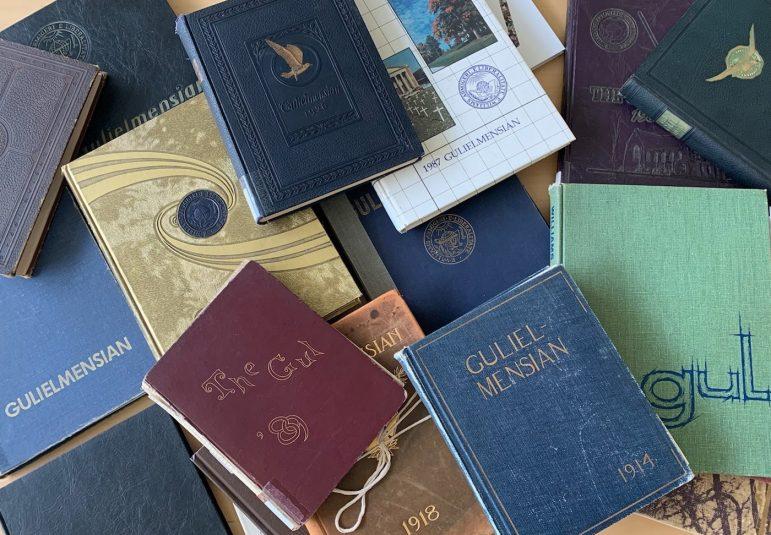

Starting in 1856, and continuing since (with the exception of a short hiatus in the 1990s), students at the College have put out an annual yearbook, the Gulielmensian, or Gul. These archives of the College’s past and present are broadly accessible in their original forms; every yearly edition since 1861 is available online, and each yearbook since 1889 can be found in print at Sawyer Library. Over the course of several rainy weekends, I pored over these old yearbooks, hoping to gain a glimpse of what Williams once was and how that relates to the College’s identity today. This is what I found.

To see the nearly unrecognizable nature of the College 150 years ago, one need look no further than the opening pages of the 1861 Gul. That year, under a formally scripted “Faculty” heading on page four, the first member listed is President Rev. Mark Hopkins, “Jackson Professor of Christian Theology.” Other notable names include Ebenezer Emmons and Rev. Isaac Newton Lincoln, who were among the 12 total professors employed by the College at the time. By 1914, however, the size of the College’s faculty had ballooned to 55, more than a quarter of whom taught Greek, Latin or German. All were white, all were male, most were middle-aged and a large majority wore a stern look of scholarly reserve that would be off-putting today.

Early yearbooks also shed light on the importance of fraternities to the campus experience. Indeed, most of the rest of the 1861 Gul is devoted to the College’s many fraternities, displayed as “Secret Societies of Williams College,” with members’ names posted neatly underneath. Little had changed by 1889, when the senior class was listed by fraternity rather than major. Even in 1955, the yearbook contained a prominent fraternity section, and those who were not members of one were called “non-affiliates.”

Despite these differences, however, the College as presented in these yearbooks is far from unrecognizable. In the 1889 Sophomore Editorial (written by seniors for sophomores), perhaps the most complimentary line is, “We realize the good work done by the few athletes you possess,” a reflection of class year competitiveness that has survived the ages. In 1913, an image of “Juniors on the Fence” depicts students sitting on a railing by a nearly unchanged Frosh Quad; an image below depicts public elections for the still-present Gargoyle Society. Social divides based on earlier schooling persisted then, too; the 1925 Gul advertised clubs for the alums of Poly Prep, Exeter, Andover and the Hill School, among others.

Reading through these old yearbooks was largely fascinating but at times presented uncomfortable reminders of the College’s past as an all-white, all-male institution. Images of Cap & Bells performances in 1924 and 1926 depict students in what appears to be blackface. In a 1965 picture, students in Sage B hold up a sign reading, “When better women are made, Williams men will make them.” In 1957, class superlatives included not only “Most Respected” and “Most Popular” but also “Class Lover” and “Woman Hater” (along with “Class Tightwad,” “Best Build” and “Used to Have Best Build”). The 1967 Gul depicts students dressed up in what appear to be bedsheets imitating keffiyehs, a traditional Middle Eastern garment, holding a sign saying “Hot Sheiks.”

Juxtaposed with these disturbing images is an enlightening archive of campus activism, both progressive and conservative. In 1912, Elizabeth H. Tilton was brought in to discuss “The Minimum Wage Bill” and Alice Carpenter to advocate “Equal Suffrage for Men and Women” (alongside F.C. Sears, who opined on “Opportunities for Commercial Orcharding in Massachusetts”). The 1965 Gul contains one page devoted to the Civil Rights Committee. That same year includes a photo of a student holding a sign saying, “Freedom now in Vietnam” alongside text that reads, “We have become more conscious of the role that students must play in society.”

In some cases, activist movements shaped entire yearbooks. The Vietnam War looms large over the 1970 yearbook, with scattered images of protest and campaign buttons calling for Nixon’s impeachment. The 1987 Gul is filled with anti-apartheid activism; for convocation, students put up 159 white crosses to commemorate those killed, preventing the procession from making a ceremonial crossing of Baxter lawn.

Prominent activist work has been far from consistently progressive, however, particularly in the years preceding the 1962 abolition of fraternities and the 1970 admission of women. The 1957 yearbook contains a lengthy editorial against abolishing fraternities which includes the line, “I can only remark that hell week [a hazing initiation practice] has long since proved its ability to unify the pledge class into a single, solid mass, thinking and acting as one man.” The 1959 Gul’s fraternity page section proudly displays a cartoon of two couples making out and another man dangling under a chandelier, martini glass in hand.

The 1967 yearbook features a defense of the College’s exclusion of women: “A continuity between generations of Williams men provides the necessary stability to enable the college to survive radical transition periods similar to the one that the Class of Sixty-Seven has sustained. Without this stability, change will be too abrupt to be long lasting or workable.” In the 1970 yearbook, an interviewer for the Gul asks a student, “Some people have called Williams a racist institution. Do you concur with this allegation?” The student, who is referred to as a “real swell gal,” a “swell scholar” and a “swell dame,” declines to answer.

These yearbooks confirm what every Williams student knows: that this campus has changed radically in the past decades and centuries. It also sheds light, however, on the enduring legacies of our college: the clubs that have persisted, the methods of activism reused and the arguments against rapid change repeated. Despite some stark differences, the Williams of 1856 is perhaps not unrecognizable from the College today.