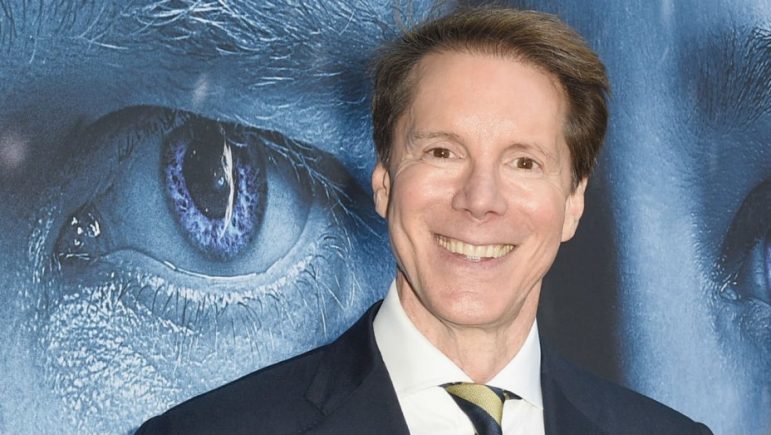

Frank Doelger ’75, executive producer of Game of Thrones, John Adams and Rome, visited the College on Thursday to discuss his path to film and television. Beforehand, I met with him at the Clark, eager to talk with him about the role of an executive producer, his time at the College and, of course, his prolonged involvement with the ultra-popular and soon-to-conclude television show Game of Thrones.

Doelger’s path to becoming executive producer of the series was an unconventional one. Before starting on Game of Thrones, he never had much of a taste for fantasy. “It was not a genre that I ever read, and it was not a genre that ever attracted me,” he said.

As Doelger began to examine the source material more closely, however, he saw an opportunity to bridge the gaps between the show’s fantastical elements and its political intrigue. “I felt in most shows based on fantasy, there’s a big divide between how the fantasy sections were handled and the non-fantasy sections,” he said. “The question was: Could you find a way to treat them the same?” This, along with rooting the show as much as possible in reality, was what Doelger saw as the show’s central puzzle.

Doelger saw many of the same potential challenges for Game of Thrones that he had experienced in other shows that he had worked on. “There are certain genres that suffer from the expectations of what the genre means they have to be,” he said. “The problem with Rome was that everyone went into Rome thinking that it had to be a stiff historical pageant because it was set in a particular period.” In the same way, Doelger became convinced that Game of Thrones could be a success if the audience could see it as about more than merely dragons and the undead.

Doelger read A Song of Ice and Fire, the first book of George R.R. Martin’s sprawling series that served as the inspiration for Game of Thrones, and founding himself impressed by the author’s storytelling ability. He found, however, that he would be better served by limiting his reading of the books. After reading the first book, he decided to stop so as to not rely on it as a crutch.

“I would occasionally have creative meetings early on. I would ask questions, and quite often I would get answers that reference the books. … I would ask ‘Why does this happen?’ and they would say, ‘Well, this happens because in the books,’” he said. “I would be curious, now that the show is over, to go back and actually read the novels,” he added. “I do understand there have been a lot of changes.”

Doelger joined the show first as a producer and, by Season 2, became the executive producer. In a show like Game of Thrones , that role includes a plethora of responsibilities that would otherwise fall to directors, since Game of Thrones has different directors for each episode. “Casting, finding locations, key decisions about the look of the show, how it’s going to be shot – these all have to be made by the executive producers,” Doelger said. In addition to these responsibilities, Doelger saw his most pertinent goal as defining the central ambition of the show and determining a path by which to pursue that ambition.

One key feature of the show, to Doelger, was ensuring that each of the show’s many “worlds” (as epitomized by its title sequence, an episode may take place in as many as eight locations) was represented faithfully. He suggested imagining that everything within each fantastical location had to come from within a 50-mile radius, and insisted that the design and construction choices for each region reflect that reality. To do so successfully would allow the audience to implicitly distinguish between every world. “If we get this right, we should be able to take a character that no one’s ever seen, and we should put them in a backdrop that no one’s ever seen, and based on how the shot is lit, the palette, the backdrop, the material of the clothing, the haircut and the makeup, we should know instantly which of our worlds our character was situated in,” Doelger said.

Stepping into an unfamiliar genre, Doelger became confident in the show’s success only after filming the execution of Ned Stark, lord of Winterfell. “When I look at how that was staged, the performances, the way it was cut, everything about that sequence to me really became clear to me that if we could continue that level of work, … that would ensure our success as we went forward.” Indeed, other shocking and iconic moments throughout the show, such as the Red Wedding [in Season 3], are based in a model established by that scene. This model was, in broad terms, “to try to play out the shock of the unexpected,” Doelger said. “To set [the audience] up by spending time with the characters involved and to let the audience experience it how the characters were experiencing it.”

Although Doelger insisted that he had no favorite character, the Red Wedding was upsetting to him for another reason: It brought about the departure of Catelyn Stark. “I thought that character as conceived by Michelle [Fairley, the actress] was wonderfully complex, wonderfully real, and there was a force and a power that I really liked the she brought to it,” he said. “I was very sorry when her end came, because I missed watching her and seeing how she did her scenes.”

Doelger said he hopes that the current and final season will live up to the high expectations set by the first seven seasons. “I’m very pleased with the last season,” he said. “I think that it’s very surprising, very shocking but very satisfying, and I think the story played out brilliantly.” Looking forward, Doelger said he could imagine a prequel show taking form in the future but doesn’t believe he will play a part in it. “My time with Game of Thrones is done,” he stated.

It was through studying literature at the College that Doelger, an English major, discovered his love of characters and storytelling. “I realized through the courses I was taking that there was something that touched me about the portrayal of characters in fiction, something that I found very compelling about the exploration of creative fiction,” he said. He was further influenced by two professors that he had as a student, Larry Grager and Robert Bell.

“I signed up for their classes my second year, and it was the first time that I had spent time in a class of literature where the passion, the excitement, combined with the analytical expertise in the section of the text, really hit me,” he said. “My conversations [with] them outside the classroom indicated to me that they were touching some sort of chord, and both of them very much encouraged me to think about those interests and those instincts as a possible career, rather than something that would end after I finished my academic studies.” He was also impressed by how the professors pulled together so many subjects into their literature, including history, politics and art. In his career, he embodied those practices as he worked to flesh out the world behind Game of Thrones.

Even so, Doelger did not immediately believe that he would find his career in theatre or television, even after involving himself in theatre while at Oxford. Only upon arriving back in New York after Oxford, accepting gig after gig, did he find himself “graduating into the business without even knowing how it happened.” He credits the College, in part, for inspiring him to pursue this field. “I think the one thing that I took away from my experience at Williams was that even though I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, I had identified an interest,” he said. “Even though the path that I was setting off on was very difficult, very competitive, with an enormously high failure rate, I was encouraged and I had the courage to at least give it a try.”

The advice that he would give to current students echoes his own experiences. “I think if people are passionate about something, it would really be a mistake not to at least give it a try,” he said. “In any career, certainly in a creative field, you will fail… While that’s incredibly upsetting, you can usually find in those failures some benefits in terms of analyzing your own work, looking to your own work and then hopefully continuing on.”