Katie Brule/Photo Editor

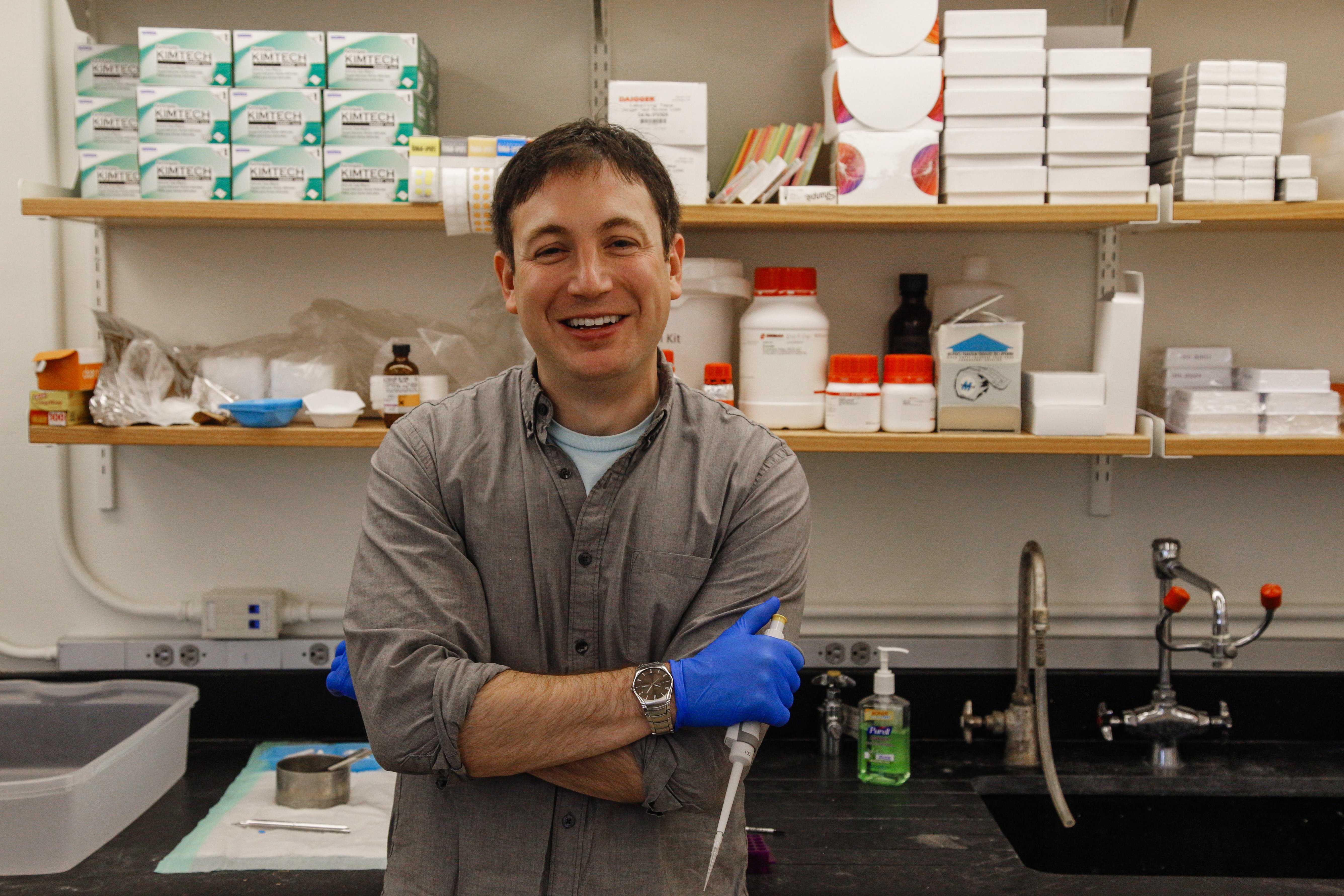

In Assistant Professor of Biology Matt Carter’s lab, cutting edge breakthroughs can happen entirely by accident.

“[My student and I] were following up on another study and we found this one brain region that seemed to be very active after an animal ate a big meal,” said Carter. The region of the brain is called the parasubthalamic nucleus (PSTN), and in the two years since they discovered it, Carter and his students have been performing preliminary research towards the ultimate goal of determining its relationship to appetite suppression and general eating behavior.

In September, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded Carter a $369,000 grant to conduct research on PSTN neurons and their role in regulating food intake. The grant will cover three years of research and includes funds for equipment, travel and improvements to the College’s science facilities. Its primary aim is to catalyze the groundbreaking research that Carter’s lab stumbled into two years ago.

“Right now, it’s the year 2018 and we still don’t have a full understanding of why a person feels hungry or feels full,” said Carter. “Even just to have the basic blueprints of ‘how does hunger work?’ would be enormously helpful for a number of diseases and understanding human behavior in general.”

The experiments that Carter’s lab performs at the College explore instinctual animal behaviors, such as sleeping, eating and drinking. While they might seem simple because of their reflexivity, these behaviors are in fact controlled by complex mechanisms in the brain.

Olivia Barnhill ’19 was inspired to join Carter’s lab the fall of her junior year, when she was taking his 300-level “Neural Systems and Circuits” class. “The things that he talks about in his class are the work that he’s actually doing in his lab,” Barnhill said. “I found it incredibly interesting and something that I would potentially want to do for a career after school.” For her senior thesis, Barnhill is working on the PSTN study, specifically with the experimental manipulation of PSTN neurons in mice through a technique called optogenetics. Optogenetics uses light to control neuron activity. The process starts by placing a gene that encodes for a light-sensitive protein into a cell. When light is shined on the protein, it reacts and either stimulates or suppresses the activity of the neuron it inhabits.

Carter’s lab has been working out how to plant these genes selectively in the brains of mice so that only their appetite-suppressing PSTN neurons are affected by light. A small fiber-optic cable implanted in the mouse’s head allows it to move freely and painlessly while allowing the experimenters to shine light into its brain and turn the relevant neurons on and off.

Gaining this control over neuron activity is crucial to answering major questions about the role of PSTN neurons in feeding behavior. “If you have a hungry mouse and then all of a sudden you turn on this appetite-suppression center, will that suppress the mouse’s appetite and get it to stop eating?” asked Carter. “Or, if you have a full mouse and it’s done eating and you inhibit this area, will it all of a sudden keep eating because it doesn’t feel full anymore?”

Any medical applications coming out of the research are hypothetical at this point, but Carter is hopeful about the study’s potential for intervention in drug-induced appetite suppression.

“People lose weight on lots of pharmaceutical treatments like chemotherapy because one of the side effects is appetite suppression,” said Carter. “So if you could shut off appetite suppression in the face of those treatments, then people could get the treatments they need without losing an extraordinary amount of body weight.”

Barnhill appreciates that the rigor and the facilities of Carter’s lab rival those of graduate and postgraduate programs; in fact, they were what drew her to the lab initially. “The fact that I could get an experience working with these really cool tools that are being used in biotech companies, I thought ‘I can’t pass that up.’”

Carter also made sure to stress the impact of student involvement in this groundbreaking work. “If students had missed this, then I never would have known about it,” he said.