The walls of Thompson Memorial Chapel are lined with the names of soldiers who lost their lives in American wars, with each entry accompanied by the corresponding date and place of death. Under the list of those who died in World War II, one name – Barton Carter, ex-class of 1937 – stands out for a subtle discrepancy: His year of death is 1938, too early for World War II. As a member of the College choir in the 1950s, Nicholas Wright ’57 was one of many alums over the years to spot the outlier and wonder about the story behind the name. Wright has made it his mission during the last decade and beyond to give Carter’s legacy wider attention, culminating in a recent push to establish a more visible memorial at the College.

Carter left his studies for war-torn Spain in 1936, working without much success as a freelance journalist while relying on a trust fund for financial support. He soon took a job driving trucks from Valencia to Madrid as part of Loyalist efforts to help the capital hold out against the ongoing Francoist siege.

Around that time, Carter submitted a letter to the editor to the Record, published on May 18, 1937. Writing in response to a resolution adopted by the College’s Model League of Nations, he argues fervently against the evacuation of foreign troops from Spain. Making clear his firm Loyalist ties, he ends his letter with the declaration, “the people of Spain will never go back to the bonds that bound them in serfdom for so many centuries.”

As he notes in the letter, he had recently started working for Foster Parents Plan, a British organization dedicated to providing support for refugee children from Madrid, a group with which he would become deeply involved.

His dedication to the anti-fascist cause soon led him to enlist in the International Brigade. After narrowly escaping an Italian ambush on the front lines, Carter was killed in the countryside west of Barcelona in early April of 1938. His life and service are documented in an article by Wright published in The Volunteer, the journal of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, along with a narrative biography by Carter’s niece, Nancy Barton Carter Clough, titled Searching For Barton Carter: The Story of a Young American Hero.

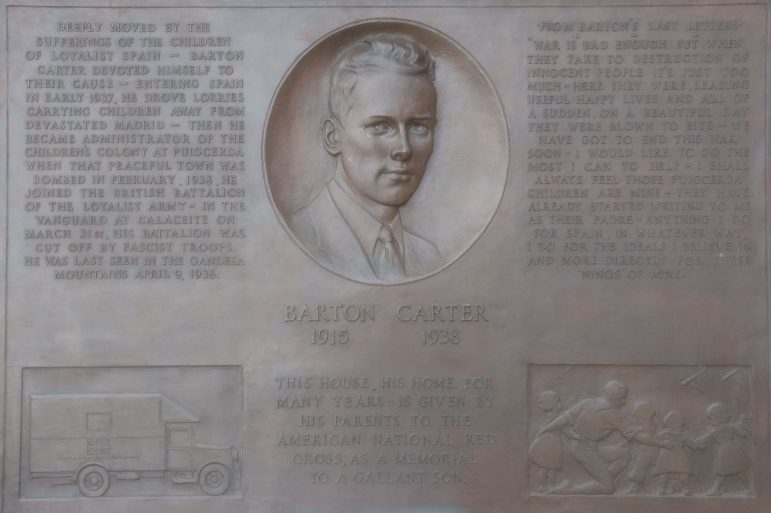

In 1941, a four-by-three-foot bronze plaque (pictured) was dedicated in tribute to Carter’s actions during the Spanish Civil War. Eventually, the plaque fell into the possession of Wright, in whose garage it remains today. He recently attempted – unsuccessfully – to donate the plaque to the College in an effort to give it a more permanent home.

Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature Soledad Fox emphasized the importance of such a memorial plaque in bringing attention to Carter’s life. “What has been important to me for a long time has been Barton Carter’s story, which was brought back from oblivion by another Williams alum, Dr. Nick Wright,” she said. “It’s a fascinating story, and now this plaque, which I believe was made to honor his memory personally, is kind of homeless.”

Fox expressed her support for Wright’s efforts to give the plaque to the College. “I think it’s important to discuss possibilities for where a plaque like this could best be preserved,” she said. “We need to think about whether it is worth preserving – and I think it is – and where it could be preserved or displayed, or at the very least, kept safe somewhere.”

Wright initially presented the plaque to Associate Vice President for Development Lew Fisher ’89, who supported the cause on principle but rejected the idea on the grounds of low storage space. “Thousands of alums have gone on to do amazing things and it’s just not possible to erect a plaque on campus for every one of them,” he said. “I am very sympathetic to this, but there’s only so much that the College can do.”

“I think the challenge is that, regardless of who supports it, there [are] only a few people who have the power to approve it,” said Chaplain to the College and Protestant Chaplain Reverend Valerie Bailey Fischer, who has done graduate work in history. “The story of Barton Carter is worth hearing, and it’s also a reminder that we should learn more about the names of those Williams alums who are on the wall. We should get the word out about Carter.”

Attempts to do so often begin with the list on the wall in Thompson. Former Managing Editor of the Record Reed Jenkins ’19, who is working on a history thesis about medical aid in the Spanish Civil War, pointed out that the erroneous placement of the name may be related to a general sense of shame surrounding American participation in the war. “The questions over Barton Carter’s memorialization speak to the complicated legacy of the Spanish Civil War in American memory,” he said. “Both Carter’s position among World War II fallen in Thompson and the fate of his memorial plaque speak to the elision of the memory of America’s involvement in the conflict and a testament to the political persecution of its veterans.”

Professor of History Karen Merrill, who teaches “Sites of Memory and American Wars” with Associate Director for Public Humanities and Lecturer in History Annie Valk, provided a similar perspective. “Certainly, Barton Carter’s name – and date and location of death – is striking amid the list of World War II deaths in Thompson Chapel,” she said. “It doesn’t surprise me that we know so little about him, given the lack of knowledge generally in the United States about the Spanish Civil War and the number of Americans who left to aid the Republican cause.”

Clough said that she decided to write the book about her uncle’s life by a desire to fill that gap. “I really wanted to tell his story because I was amazed at what he did in just two years,” she said. “I felt that I just had to tell the story of this true, true hero.”