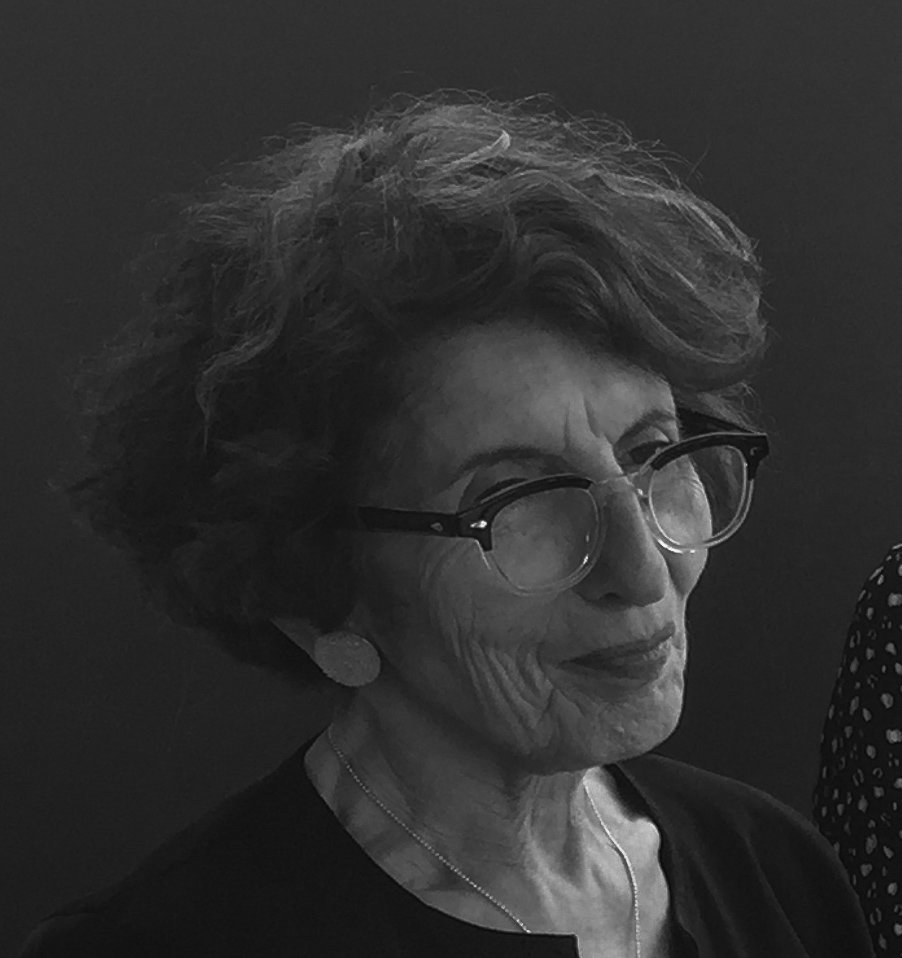

Photo courtesy of Brian Martin.

On Aug. 31, French Professor Nicole Schott Desrosiers passed away. Her commemoration was held on Sept. 23 at Cranwell Resort & Spa in Lenox, Mass. Desrosiers played many roles in her life – professor, mentor, wife, mother and grandmother – but above all, she was a visionary.

Desrosiers was born into a German-Jewish family, the daughter of Harry and Ruth (Katzenstein) Schott. Because of their faith and fear of persecution, her parents fled Nazi Germany and emigrated to Le Puy, France in the early 1940s. Despite the horrors and struggle of World War II and the Holocaust, Desrosiers completed her secondary and tertiary studies in Clermont-Ferrand, France. Then, in 1966, she was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to the U.S., on which she completed a master’s degree in American literature at Mount Holyoke. Dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge, Desrosiers pursued both a master’s degree and Ph.D. in French literature at the University of Massachusetts.

It is safe to say that Desrosiers was fully prepared to embark on her career as a French scholar, writer and professor. During the early stages of her career, she chaired the world language department at Lenox Memorial Middle and High School for 22 years and taught at both Trinity and Bennington. Upon returning to the Berkshires, Desrosiers became a lecturer in the romance languages department at the College for 44 years, teaching both graduate and undergraduate courses in French literature, translation and art history. Her passion for education has been recognized by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the French government, which awarded her with Les Palmes Académiques.

“Having survived the Holocaust, she [became] a scholar of Albert Camus – the great existentialist philosopher who based many of his philosophies on the idea of resistance in the face of hopelessness, violence, exploitation and danger,” Brian Martin, professor of French, said. Desrosiers was extremely excited for her brand new course on Camus, “Albert Camus and the Philosophy of Living,” which she would have taught in the fall of 2018. This course emulates much of Desrosiers’ life, “whether [it was] her family facing mass murder in Europe by the Nazis or little struggles that [she went] through everyday, there is pleasure: friendship, family, art and beauty. That was Nicole. She was so full of positive energy,” Martin said.

Desrosiers was an extraordinary mentor to many of the professors in the romance languages department as well as the graduate art history program at the College. “I knew Nicole for about 15 years, and from the beginning, she was extremely warm and eager to talk about anything to do with language, France and art,” Katarzyna Pieprzak, Associate Dean of the College and professor of French, said.

While she had a genuine passion for ideas, books and cuisine, Desrosiers’ love for people and teaching was at the forefront of her life. “She was always interested in mentoring [us]. That’s when I realized how sincere and generous she was and from then on we developed a deeper friendship,” Pieprzak said. “Naturally, she loved her native language, but most important to her was cultivating her own battery of useful ways to teach French to others,” Karen Kowitz, program administrator for the graduate program in art history, said. “She taught French to students with no prior knowledge of the language, and she would continue to work with anyone who requested additional study during the summer… She was their teacher for as long as they needed her,” Kowitz said.

It was in Desrosiers’ character to go above and beyond with both her undergraduate and graduate students at the College. “[She] had a kind of ‘tough love’ approach to teaching – lots of playful ribbing mixed with sincere and personalized encouragement – and I’m grateful to have studied with her,” Jake Gagne ’19, graduate student of art history, said.

Her generosity and enthusiasm never went unnoticed, and “she possessed an infectious zeal for life, which she shared with everyone around her,” Nora Rosengarten ’19, graduate student of art history, said. “[Desrosiers] had seemingly limitless energy, always making herself available when we needed to speak with her… It was obvious to all of us that she cared deeply about our progress and that she took joy in our success,” Jenna Marvin ’19, graduate student of art history, said.

For many language students, Desrosiers’ “Intermediate French II” was their first introduction to learning about 19th century art; however, she found a way to make everyone feel comfortable and at ease with the coursework. “Her pedagogy centered on applying the messages of the paintings of yesterday to our lives today, and I am forever grateful to her for these literary lenses she provided me,” Theophyl Kwapong ’20 said. “Going to class was always a joy because she allowed us to bring our full selves to the classroom.”

As much as she was a distinguished professor, Desrosiers was also a devoted wife, loving mother and cherished grandmother. She was predeceased by her loving husband, Paul Desrosiers, but is survived by her close-knit family: “her son David, his wife Wheatly and their daughter Lulzime; her son Daniel, his wife Bridget and their daughters Camille and Patrice; her brothers Henri, Gaston and Marcel, and their families, all in France,” according to her family’s obituary.

Outside of the classroom, Desrosiers was also the cofounder of the Berkshire Organization of Language Teachers and a member of both the American Association of Teachers of French and the Berkshire International Club.

Famous for her infectious optimism, elegance and the pleasure she took in sharing meals, advice and surprise gifts, Desrosiers will be remembered fondly by students, faculty, family and friends. “She was the model of a strong woman,” Pieprzak said. All who knew her elle nous manque beaucoup.