In The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, witnesses ranging from Sigmund Freud to Pontius Pilate are called to testify on whether Judas Iscariot should go to heaven.

Last weekend’s theatre department performance of The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, by Stephen Guirgis, was notable not only for its star cast, intelligent humor and philosophical weight, but more so for its unique inclusion of student input in the creative process.

The show was led by director Shadi Ghaheri, visiting lecturer in theatre, and dramaturg Catherine María Rodríguez, both of whom emphasized the importance of actor participation in their process. The play, which imagines Judas Iscariot on trial in purgatory, was grounded by the exceptional Maya Jasinska ’21 as defense attorney Fabiana Aziza Cunningham, Samori Etienne ’21 as prosecuting attorney El-Fayoumy and Peter Matsumoto ’20.5 in the role of Judas himself.

For many students, the inclusive rehearsal process had a strong impact on the quality and value of rehearsal time, offering a much-needed change in the wake of the theatre department’s cancellation of Beast Thing in the fall. Ghaheri and Rodriguez began their process with “table work,” in which the entire cast and crew read and analyzed the show. “Normally in shows, we do that once or twice for the first couple days, and then we stand up and get on our feet,” Matsumoto explained. “For this show, we did it for a week… It was so much, but at the same time it was super helpful because the play is so damn long, and it’s so dense.”

This process led to collective decisions to revise some dialogue in the show, a common occurrence during table work. “There’s a lot of really bad homophobic slurs, really bad misogynistic slurs that come from a lot of the characters, Judas included,” Matsumoto said. “None of us felt that [these were] necessary to the show, [they] didn’t add anything and really it detracted from the character of Judas that we were trying to portray.”

Actors also had input in aesthetic elements of Judas; actors were asked to brainstorm what their characters looked like and bring their ideas to the costume designers. These ideas were then incorporated into each character’s ultimate costume design. Ben Weber ’21, for instance, thought that his character likely biked to work and even determined that he died when he was hit by a truck while biking to Montreal. Weber’s ultimate costume design included cycling tights and a helmet.

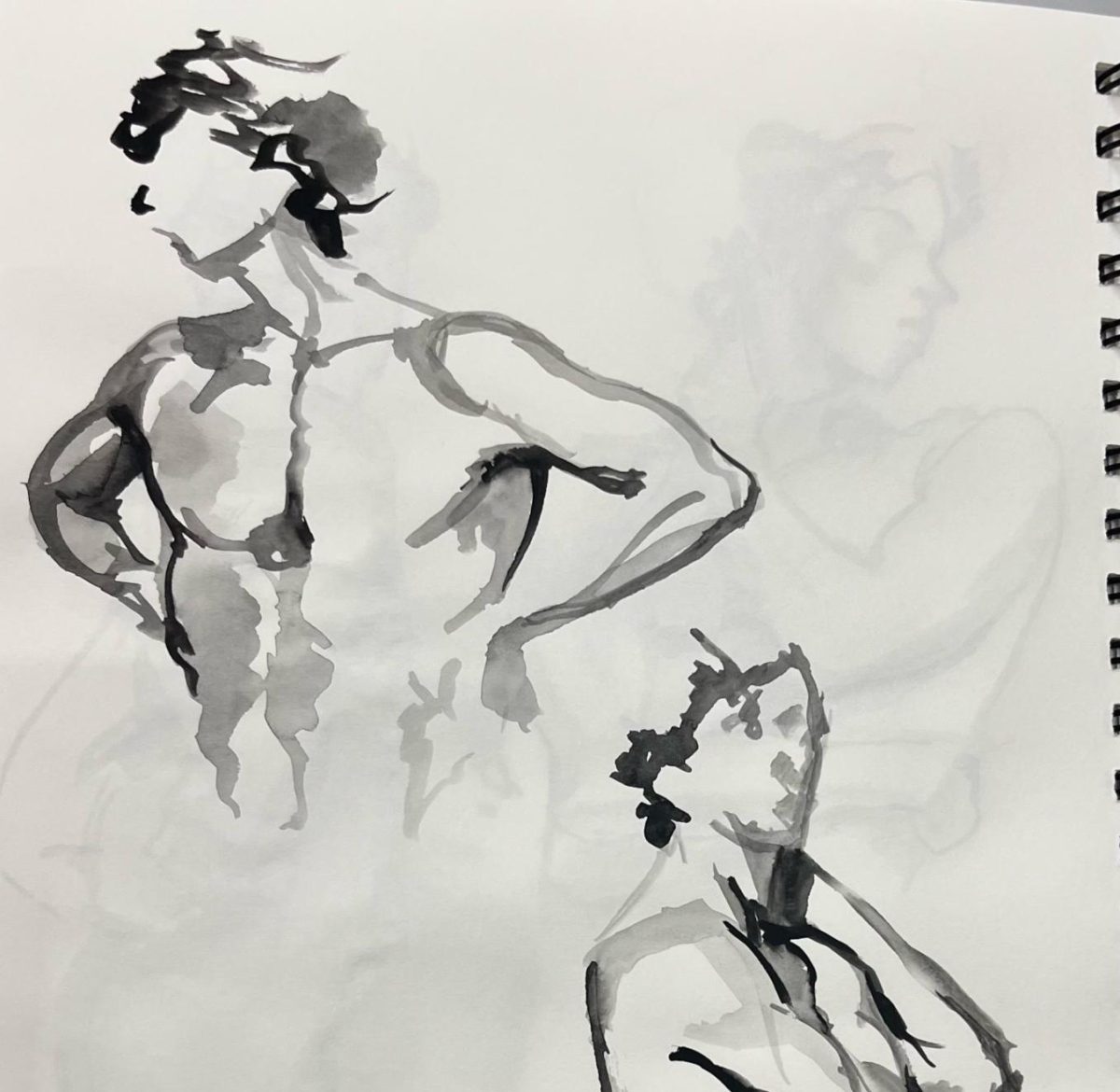

Character movement was also consciously led by the actors themselves, beginning from the first reading. Whenever any scene was first discussed, Weber explained, a group of actors would sit in a circle, read it through, discuss it and then perform it in the way that was most natural to them. “[Ghaheri] would have little tweaks, but it was really a ‘follow your instincts’ sort of thing,” he said. Actors’ blocking decisions were sometimes even spontaneous, with the two attorneys, Etienne and Jasinska, receiving free rein to walk around the courtroom throughout much of the show.

Rehearsals also pulled from student talent in non-acting capacities. The show contained several dance routines choreographed by Kester Messan-Hilla ’21 (Simon the Zealot/Pontius Pilate), including a dance to Taylor Swift’s “Look What You Made Me Do” to introduce Satan, played by Mira Sneirson ’22. According to Weber, these dances were constructed organically, using student innovation as their bulwarks.

The erosion of directorial hierarchies was paramount in Ghaheri and María Rodríguez’s vision. On the first day of rehearsal, actors received community agreements that included standard guidelines for arriving on time and being off-book, but also emphasized the right of actors to say ‘no’ at any time and push back against a director’s idea of how a character should be played. Jasinska found this collaborative environment extremely useful for her character. “For my character, because there was a lot of heavy material, I would meet one-on-one with the director,” she said. “We would have separate meetings, essentially.” Weber also worked to add a level of levity to his character that, while not scripted, was soundly encouraged.

This collaborative mindset was honored for concerns outside of the production as well. After several actors felt stressed out about managing schoolwork and the production, the group discussed “the things that were burdening us that we thought we weren’t allowed to say,” according to Weber. “We took a break to be with each other,” Jasinska added. Rehearsal ended an hour earlier that day with actors feeling acknowledged and heard. “When parts of the process became difficult for members of the cast, being able to discuss and share what we were experiencing significantly built trust and community in the space,” added associate director Nadiya Atkinson.

The cast said that Beast Thing, which included many of the same cast members, had a decidedly different atmosphere. After the theatre department cancelled Beast Thing, actors cited factors ranging from a lack of a student voice to a dehumanizing rehearsal process. “We were not listened to in Beast Thing; we were forced to just plow through,” Jasinska, who was in both shows, said. “When we raised concerns, it was just sort of thrust aside.” Concerns about graphic images, for instance, were ignored. In this show, by contrast, when actors raised concerns about the images associated with Pontius Pilate, played by Messan-Hilla, a Black man, threatening sexual assault against Fabiana Cunningham, played by Jasinska, a white woman, the cast collaboratively rethought elements of the scene.

The openness of the show’s creative process was epitomized by open rehearsals, meaning any member of the College community could sit in on rehearsals. This gesture was meant to allow the community a way into the show’s process and create a less secretive environment, and theatre faculty would sometimes stop by, though students rarely did so.

Chair and Associate Professor of Theatre David Gürçay-Morris ’96 said he does not believe that the Judas process was necessarily more quantitatively collaborative that others, yet he commended the unique quality of the show’s teamwork. “I couldn’t be happier that we have all been able to learn from Shari [Ghaheri] and Cat [María Rodríguez] over these past few months, both in their approach to making theater and to forging a community through that artistic work,” he said.

In the end, according to actors, the open process paid off in the final product. “When you have such a big cast where everyone gets to make their own decisions, sometimes it feels a bit chaotic, but in this world it made it feel a bit textured,” Weber said. “Every single character that you saw on stage was their own person, with their own background.” For Jasinska, the process enhanced not only the show’s ultimate quality but her experience in performing in it. “The final product lent itself to us feeling like we had so much ownership over the show,” she said. “It made me really proud to to be a part of it.”