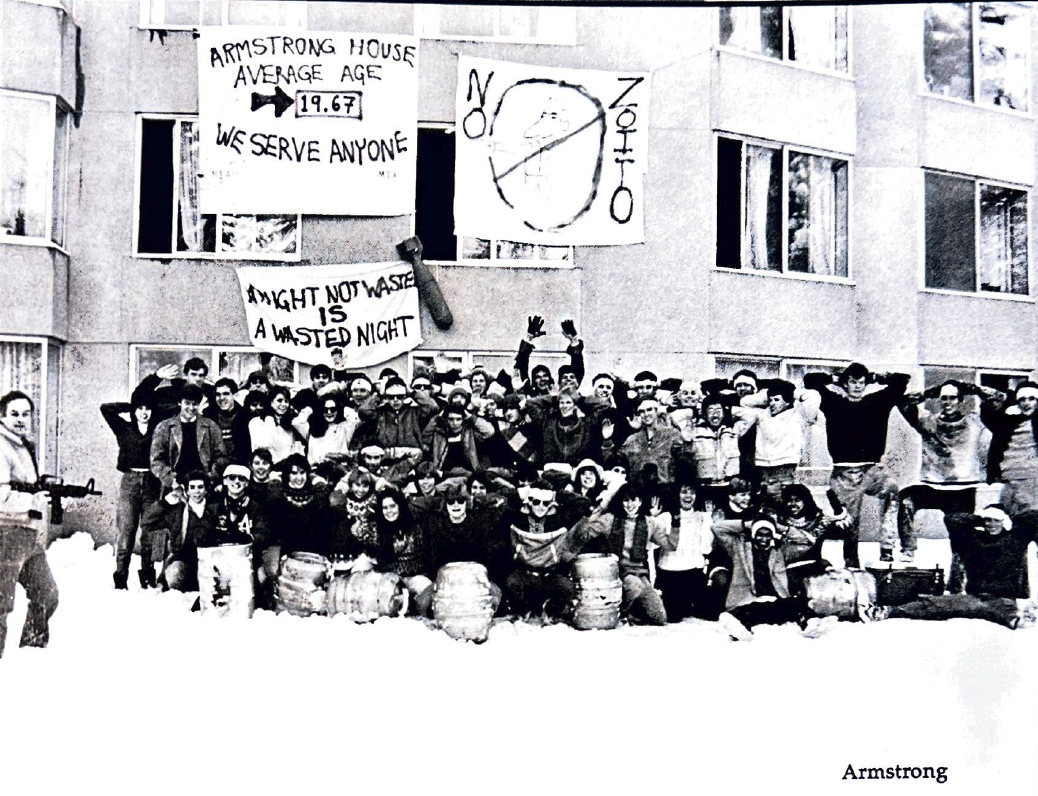

It was an overcast Sunday morning in February 1987. Snow softened the sharp concrete corners of Mission Park. Campus was quiet, but just outside the riot-proof entrance to the dorm, the mood was far from laid back. Dozens of students gathered outside Mission with a large banner that read “No Zoito.” Another read “Armstrong house average age 19.67 we serve anyone.” What appeared to be a bomb hung from the third floor of the building. Someone was brandishing a fake machine gun.

This bewildering scene was the product of a feud between then-Williamstown Police Chief Joseph Zoito Jr. and students accused of underage drinking and destruction of property. While disagreement between partygoing students and local law enforcement may sound typical, the battlefield for these skirmishes was definitely exceptional.

The previous night, Seth Rabinowitz ’89 and some of his fellow Missionites had thrown a rager of epic proportions that crawled its way through the halls of their brutalist home. “Legend still tells that the largest keg party ever at Williams College was held in the Mission dining room, and it was so outrageous that it brought [on] reforms,” Rabinowitz told the Record. “I don’t know if that’s true or not, but we claimed it was true at the time.”

The reforms to which Rabinowitz referred limited access to kegs on campus in the next two years, sparking a sprawling discourse across the pages of the Record and the now-defunct College yearbook the Gulielmensian (Gul) — the center of which was, of course, a keg.

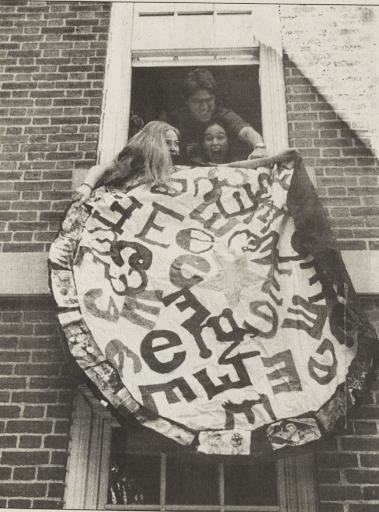

Now mostly extinct on our campus, kegs were the lifeblood of the College’s party scene in the ’80s. According to Rabinowitz, some Mission parties would have a keg on every landing of every stairwell in the Armstrong-Pratt side of the building. In the 1987 edition of the Gul, a number of students are pictured holding or transporting kegs. The keystones of the post-bacchanalia picture in front of Mission were the kegs.

In the mid-80s, state legislatures across the country began to pass laws that raised the drinking age to 21. In light of that national development — and a new set of party policies — the 1984–85 academic year began with a concerted effort from the College’s administration to cut down on drinking. Plans included “dry” social opportunities for the new crop of first-years and an attempt to get the kegs off the scene.

A Sept. 11, 1984, issue of the Record tells of a sober “Casino Night,” which, although enthusiastically supported by some Junior Advisors, was not entirely successful in curbing the keg-drive. “Several freshmen said they left Casino Night early to find other parties where beer was available,” the Record reported.

Later that year, the Record ran a special edition about the problem of alcohol at the College, pointing out that, even with new first-year policies, alcohol-related health cases at the College infirmary were still on the rise.

When Massachusetts Governor Michael S. Dukakis signed a bill to bump the state’s drinking age to 21 in 1985, the percentage of legal drinkers on campus plummeted. To put it in Chief Zoito’s words: “The drinking age is 21. That cuts three classes right out of the ballgame,” he said in the ’87 Gul.

But for Zoito, this wasn’t just a numbers game — morality was at stake. “You have a problem at that school,” he continued. “Learning how to drink isn’t part of your curriculum.”

As the 1986–87 school year began, tensions over beer access frothed over. In early November, a student was arrested for providing alcohol to first-years, the Record reported. The next week, the College’s deans introduced a ban on students charging fees for party entry.

On Nov. 25, the Record announced that it had fired most of its senior editors on the basis that they had colluded with Chief Zoito to put the cosh on parties. “In the wake of accusations of complicity with the police in a plot to eliminate parties on campus, editors-in-chief R.P. DeMott ’87 and John Schafer ’87 have been forced to resign,” the Record reported.

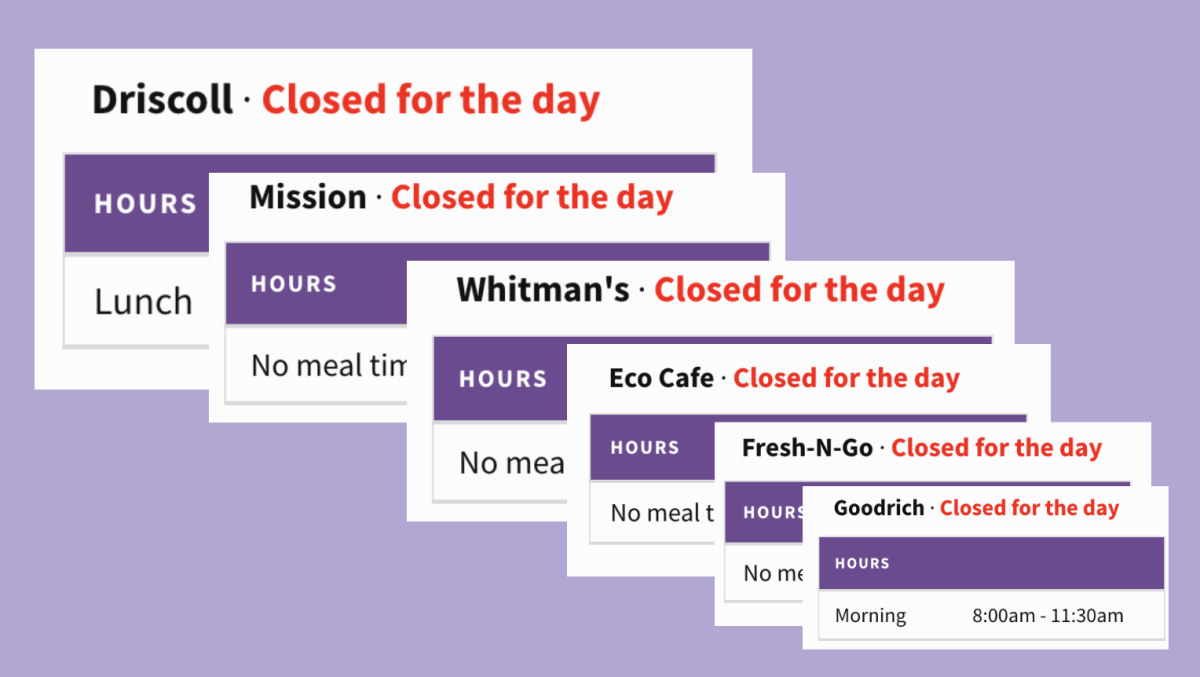

This crackdown didn’t deter the Ephs’ undying love of alcohol-fueled hobnobbery. So began the hunt to find workarounds. “After [underage drinking] was enforced more strictly, there were more parties at the different houses,” Wendell Chestnut ’88 said in an interview with the Record. Mission, he said, became the ultimate destination.

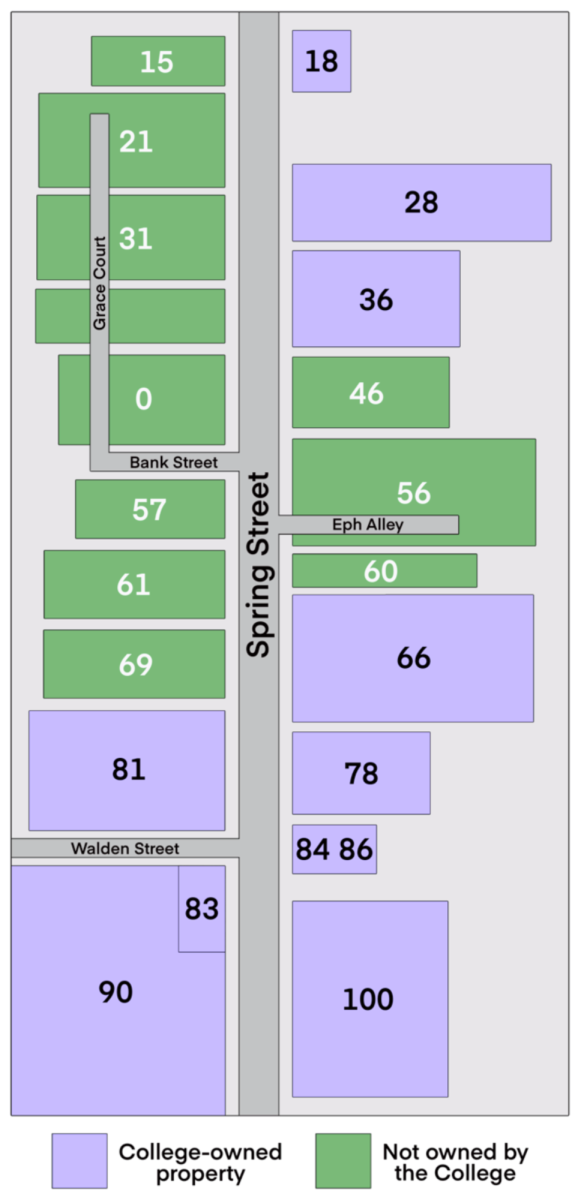

According to students at the time, Mission was a desirable party spot, located deep within campus and further away from the watchful eyes of the police. “Mission Park in a basement is pretty benign compared with a house on Hoxsey Street, right?,” Rabinowitz said. “You’re asking for trouble in a house on Hoxsey Street.”

While Mission may sound like the last place current students would want to throw a party, it had its shining moment as the center of the social scene on campus, according to Rabinowitz. Back then, “Mission party” was far from an oxymoron.

One of those parties was, as Rabinowitz dubbed it, “The Great Keg Party of ’87.” “That was the one where, I believe, it was the beginning of the end,” Rabinowitz said in the Record.

“Armstrong sponsored, I think there were 12 kegs, which was a lot,” he continued.

Twelve kegs is indeed a lot, but it might have been even more. “I think we had over 20 kegs,” Mark Raisbeck ’89 said. “I think it was like 25 kegs,” his friend and the president of Armstrong house, Ajata (AJ) Mediratta ’89 added.

While this night was undoubtedly special, it likely followed the common Mission rager formula of three distinct phases:

“So the stairwells were number one,” Rabinowitz said. “The stairwells offered an exciting sense of verticality to the Mission party experience,” Rabinowitz added. “There’d be a keg on one landing, and then, you know, you’d go up and down.”

“Then the basement was number two … but the basements were for bigger parties,” Rabinowitz said. “Those were, you know, as charming as you might imagine in a basement with no ventilation, reeking of stale beer, et cetera. They were great.”

After the kegs in the stairwells ran dry, partygoers would move along — but instead of walking as far afield as Agard or Meadow, many would just stay in Mission.

The third phase of the Mission party trajectory led to the dining room. “[The dining room] was more of a special thing, and those were big parties with hundreds of people,” Rabinowitz said.

After all three phases had come to a close, there was of course the aftermath. The night of The Great Keg Party, these consequences were enormous. “It was a perfectly fine party, but what happened was some underage girl from town snuck in and we had no idea, but she got picked up on her way home, and [the police] tracked [her story] back to our party because there was a stamp on her hand,” Mediratta said.

Mediratta ended up taking the fall. “Since I was the senior president of the floor, I think I signed for the kegs,” he said. This put Mediratta in legal trouble. “She filed some action against me and I ended up having to go to court a couple times to defend it,” he said.

Still, he largely avoided repercussions. “The school sort of admitted some culpability, since, you know, I had played by school rules and even hired campus security,” he said. Since Mediratta hadn’t done anything wrong by school policy, the College paid for his legal defense, according to Mediratta.

This all led to the scene in front of Armstrong where students protested Zoito’s involvement with Mission’s affairs. “It was [the police] giving us a hard time for throwing a big party.” Even people not involved with the party joined in on the protest. “The guy with the machine gun [was], I think the custodian,” Raisbeck said. “We were friends with those guys back then,” Mediratta added.

While many gathered to oppose Zoito, not everyone was on board with the frequent debauchery at Mission Park. “There were people who didn’t like it and said that it was a bunch of degenerates, and it was, I’m sure, all of the same complaints: misogyny and any number of things,” Rabinowitz said. “And it was probably a pretty, you know, a full-throated environment. It was not as politically correct.”

In a Feb. ’87 edition of the Record, Dean of Students Mary Kenyatta explained that the dominant ethos of Mission was “party party beer and don’t try to do anything different.”

Even some participants in the Mission parties desired a different vision. “I can’t believe I’m confessing this, but I always had apple juice in my cup,” Chestnut said. “I was like, ‘I can’t risk getting drunk.’”

“Apple juice looks like beer, and no one’s really gonna question you as long as your cup looks full,” he added. “So apple juice was the way to go for me.”

There was, of course, also physical property damage that occurred due to the Mission ragers. This was the case on nights like the Great Keg Party of ’87. “We took it as a point of pride, that it was so big and debaucherous, that it led to problems,” Rabinowitz said.

The Feb. 23 edition of the Record following the incident reported that there was significant damage done to multiple student vehicles in the Mission parking lot and multiple TVs were smashed in Mission Lobby. Zoito was characteristically unimpressed, announcing that the investigation started the same night the vandalism occurred. “I know the boys were working on them last night,” he said.

In spite of his responsibilities, maybe a part of Zoito respected the game. In a comment to the Gul, Zoito remarked on the sheer volume of alcohol consumed. “Twenty kegs of beer, divided by 400 students, that’s 15 cups of beer [per person] — everyone’s drunk, right?”