In Building 8 of MASS MoCA, you may come across a room that looks more like an active photography studio than a curated gallery, filled to the brim with wooden chests with tiny drawers, recordings of voicemails, and cardboard boxes labelled “animals” and “other peoples’ houses.” The room contains photographer and filmmaker Randi Malkin Steinberger’s latest exhibition, The Archive of Lost Memories.

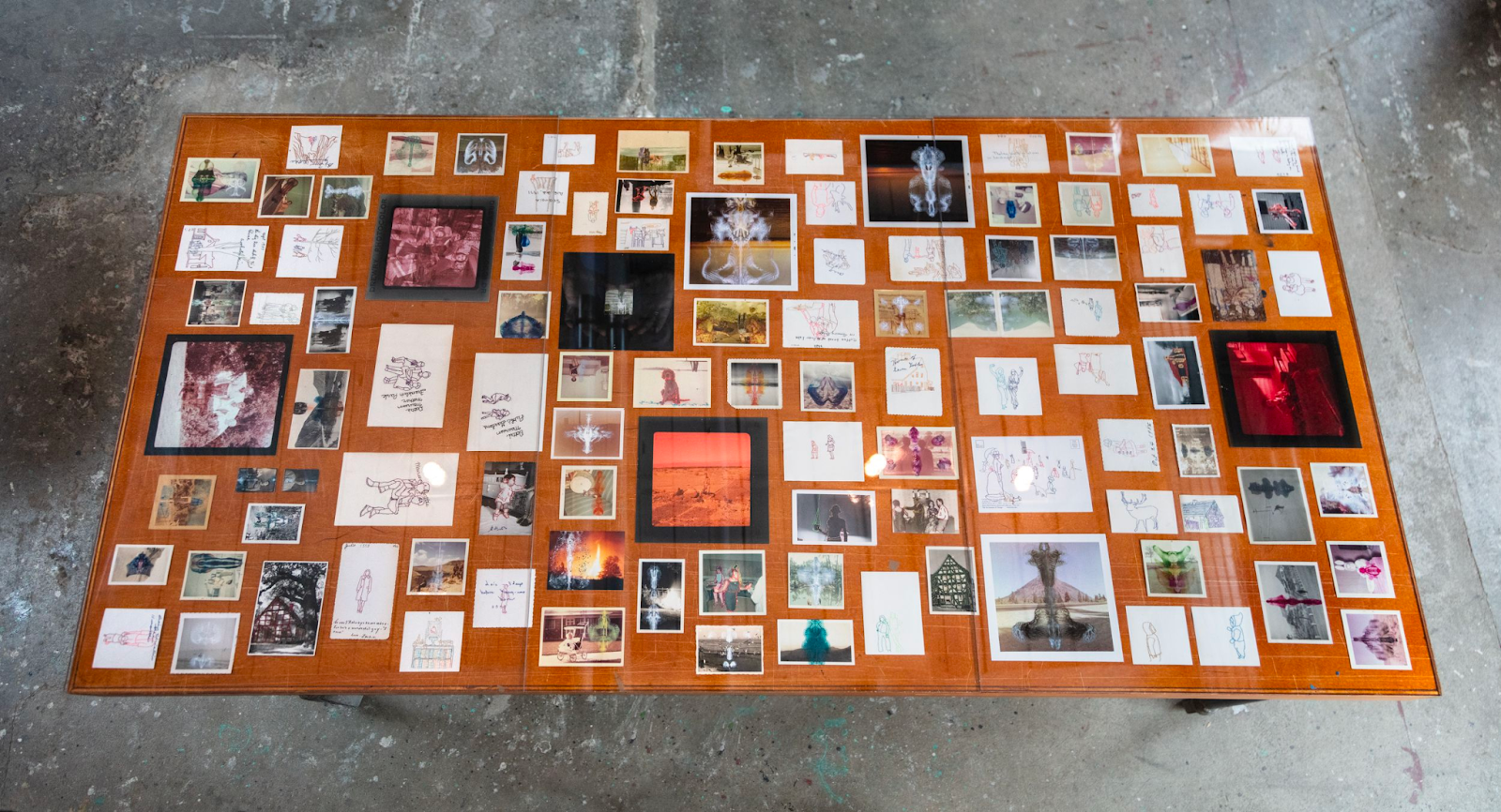

Described on Steinberger’s website as a “cabinet of curiosities,” the installation — which opened on April 5 and continues through June 29 — incorporates Steinberger’s own photography with forgotten prints, slides, and tintypes from estate sales, eBay, thrift stores, and antique markets.

Images adorning the walls focus on familiar scenes: a family portrait, a teenage girl laying on her bed, a table set for a holiday meal. The works display an adorned version of quotidian life dotted with household objects like thread and nail polish. “[The embroidering and painting process] is so slow and intentional, I really have time to feel like I’m connecting with the image or the past people,” Steinberger said in an interview with the Record. “Both of those things, sewing and nail polish are domestic items, just like the snapshots.”

For Steinberger, the process of adorning photographs allows her viewers to engage with the images in a more personal way. She often adds blots of paint to the pictures before folding them in half to create an inkblot-like effect that empowers the viewer to craft their own meaning. “There’s so much imagination that I’m putting into interpreting [the piece] by adding this old fashioned psychological Rorschach,” Steinberger said. “It’s creating another ability to enter in and imagine something … It’s another way of relating to the photograph.”

By combining the archival nature of photography with present-day tweaks and embellishments, Steinberger’s work straddles the past and the future. “I feel like I’m moving forward at the same time I’m going backwards,” she said. “[I’m] connecting to the past, to the old things, but still super interested in whatever is the consumer technology of the day to document my own life.”

Beyond embellishing forgotten pictures, much of Steinberger’s work centers around paying attention to otherwise abandoned objects. “For some reason, I feel indebted to the memory of the collective loss of these precious items that we all treasure,” she said.

This concern is evident in Steinberger’s reconstruction of torn-up photographs. “I found [photos] around photo booths in the ’80s in Italy,” she said. “A lot of them were just ripped up because [the subject] didn’t like them, or the chemicals were bad in the machine … I would just piece them back together and put them in notebooks.” The photographs, now pieced together, are displayed on a large window, allowing the sunlight to flow between the tear marks.

Despite preserving memories, film photography is an inherently ephemeral medium, Steinberger explained. The film slides pasted against the windows are both at their most visible and at their most vulnerable, with the sunlight clarifying the images while also causing chemical damage. Some of the decay is already evident, but Steinberger chooses to frame it as a lesson in letting go. “Putting them up in the light is going to ruin them,” she said. “Time is gonna play its part in that, and that’s okay.”

Although much of the installation centers on forms of photography that are now considered antiquated — silver gelatin prints, daguerreotypes, and film — it also draws on contemporary digital photography. One of Steinberger’s projects, a short film titled It’s No Accident, showcases every accidental video that Steinberger has ever taken, both on her phone and using her professional videography equipment.

“[The film] becomes a document of my life,” she said. “I don’t choose what moments are in there, but at the same time, it covers my work and my personal life and everything. In a way, it’s similar to working with other people’s memories, because there’s just a lot of blanks, and I have to kind of fill in the blanks somehow.”

In her work, Steinberger also explores how the transition to digital phone photography will impact the storytelling aspect of visual recordkeeping. “I don’t even know if people are thinking about their family records,” she said. “I think people feel like Facebook is the archive of their families. It’s so different, and I don’t know how parents are going to pass these [images on] … I still don’t understand what’s going to happen.”

Regardless of the medium, Steinberger dedicates herself to the preservation of forgotten images. “I feel like I’m responsible for all these lost memories,” she said. “I just can’t throw them away.”