In the spring of 2001, a pallet of unsealed moving boxes was unloaded from a truck at the Williamstown post office. Inside were thousands of VHS tapes and photo negatives, each meticulously labeled in Dari, Pashto, and English. They were transferred to the old basement of Stetson Hall, where they would become the Williams Afghan Media Project.

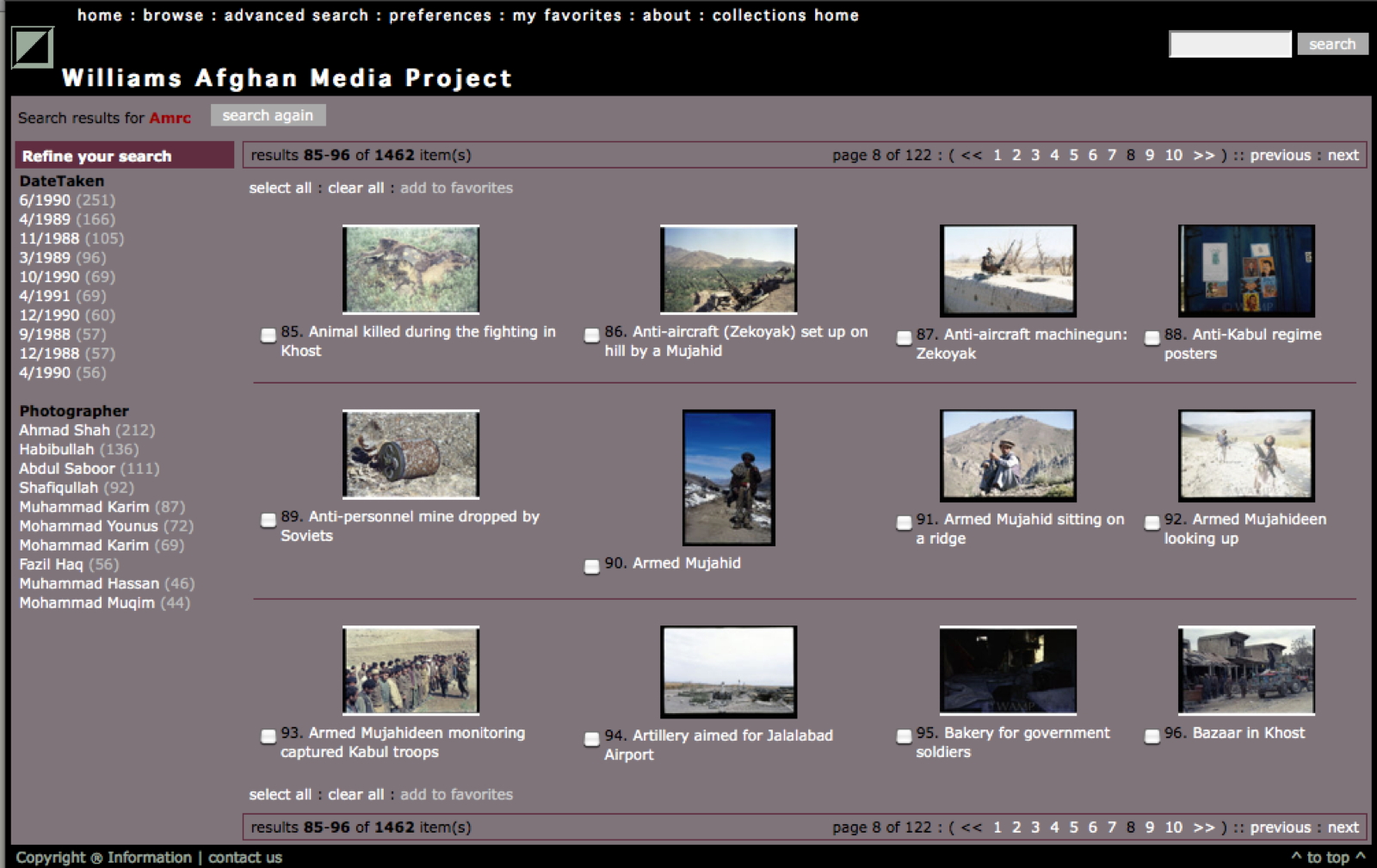

Over the next few months, Professor of Anthropology David Edwards, along with a small team of American and Afghan technicians, digitized and archived over 3,000 hours of film and 2,000 photographs of Afghanistan from the ’80s and ’90s. The material had recently been donated to the College by the Afghan Media Resource Center, creating one of the only online archives dedicated to audiovisual material from Afghanistan at the time, according to Edwards.

The center’s archive was founded in Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1987 “to assist Afghans to produce and distribute accurate and reliable accounts of the Afghan war to news agencies and television networks throughout the world,” according to its website.

For Edwards, though, there is more to the story: The center was founded in part with funding from the State Department under the Reagan administration. “What they wanted was for the crimes of the Soviet Union [in Afghanistan] … to be exposed the same way that the U.S. involvement in Vietnam had been exposed to public scrutiny,” he said. “They realized that, in the Soviet Union, nobody really knew what was going on in Afghanistan, because no journalists were willing to go there.” Despite Washington’s desire for a media exposé, only a small amount of the center’s footage ever ended up on television screens on either side of the Iron Curtain, according to Edwards.

Instead, all of the tapes and photographs sat in a home in Peshawar for a decade, collecting dust and beginning to warp in the city’s heat.

Concerned about heat damage and the growing Taliban threat in neighboring Afghanistan, Ḥājī Sayed Daud — the center’s then-director — reached out to Edwards through a mutual friend. Daud asked him to come to Peshawar and see how much of the archive’s contents could be relocated.

Edwards, who studies Afghanistan and lived in Peshawar during his doctoral studies, made the trip over spring break in 2001 with photographer and documentarian Greg Whitmore ’98. At the time, Whitmore was working on independent photography projects with Professor of English Shawn Rosenheim.

A few weeks later, Edwards and Whitmore flew to London, and then Islamabad, and after missing connections left and right, had to hitch a ride to Peshawar with a United Nations convoy. Once the two arrived in the city, they met with the center’s leadership and discussed moving some of the archive to the College.

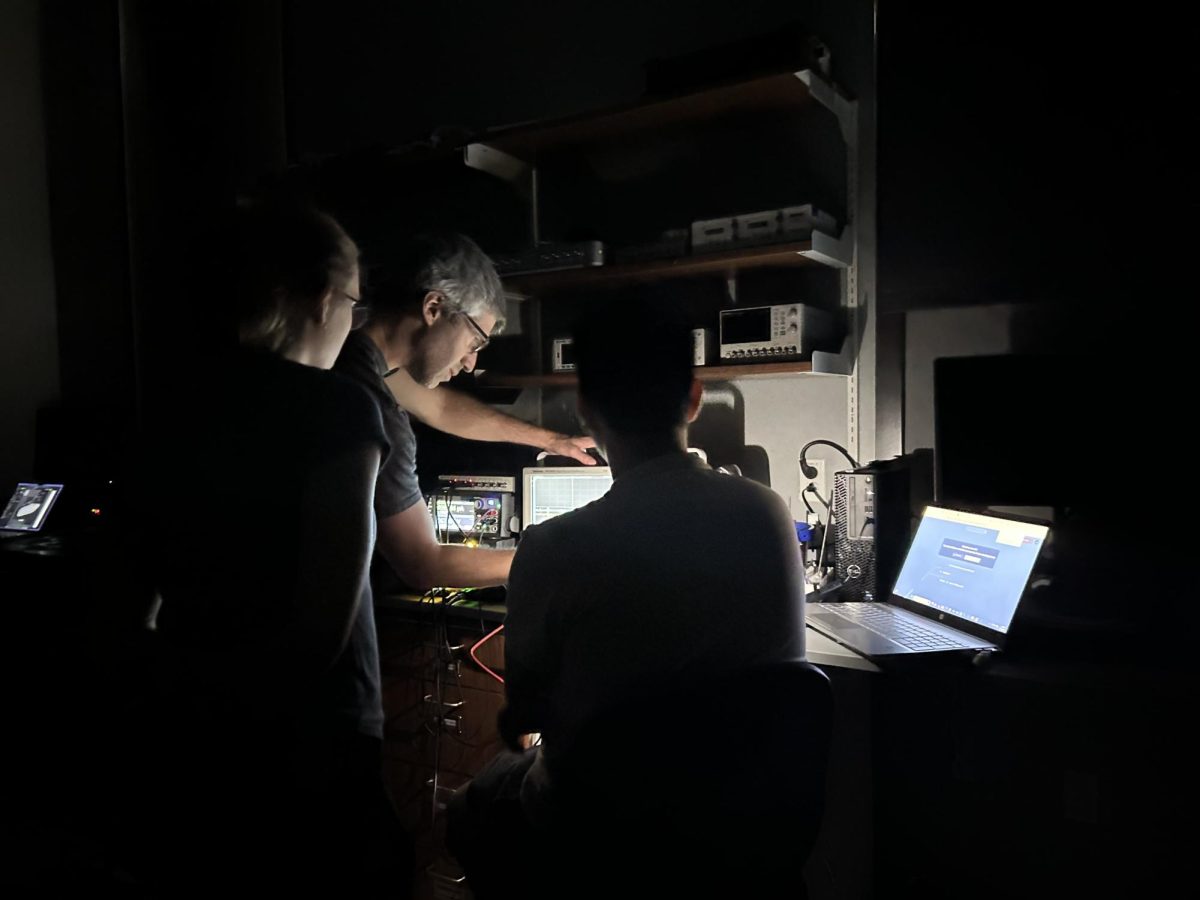

The pair then used funding from the College and the U.S. consulate in Peshawar to begin shipping boxes to Williamstown. Edwards, Whitmore, and four Afghan journalists from the center in Peshawar spent the summer in Williamstown digitizing the records. Whitmore recalled that the six of them would often go on hikes together — on one such occasion, they ran into a black bear. In their minimal free time, they even made a fictional short film about a llama entitled Who Bought? Who Got?

Aside from the occasional bear encounter, the group spent most of their time that summer working. Because all of the material was analog, digitization took place in real time: Each hour of film needed to be played back for an hour to be scanned. The work was grueling. “We were working probably 20 hours a day, just digitizing,” Edwards said.

By the start of the fall semester, the team had added all the materials to the archive’s new website, which is now offline. The College celebrated the project’s success by releasing a press statement on Sept. 10, 2001.

As we now know, the following morning would forever change the relationship between the United States and Afghanistan. Edwards recounted how one of the four Afghan journalists who had been working on the project was flying back to Peshawar on the morning of Sept. 11, and was pulled out of the security line at Newark International Airport under suspicion of involvement in the attacks.

After 9/11, news outlets began to scramble for a glimpse into the nation dubbed the “graveyard of empires.” Despite the repository of archival footage at the College, not many b-roll researchers knocked on Edwards’ door.

That is, not until an article titled “ARTS IN AMERICA; When Afghanistan Collapsed,” appeared in the New York Times on Oct. 2. The article detailed some of the content in the College’s archive, especially the content about mujahideen fighters. According to Edwards, the article brought the College’s archive into a media spotlight.

Then, the floodgates were open, and Edwards’ phone became a veritable hotline for cable networks reporting on Afghanistan. They had almost no footage of the country, and after 9/11, raced to find something for news broadcasts. Initially Edwards was hesitant to provide access, but after a few weeks he allowed some of the networks to use the footage.

“I was inundated with telephone calls from 60 Minutes and basically all of the networks, because they all wanted images of Afghanistan,” he said. “They didn’t have any. And suddenly they hear that this professor in Williamstown has 3,000 hours of footage.”

Sometime in the late fall, a CNN producer reached out to Edwards, but this time with a strange ask. Instead of soliciting material, he asked Edwards if he would accept new material and add it to the College’s archive. The offer was for 1,500 of Osama bin Laden’s personal cassette tapes, obtained by CNN from a cassette shop in Kandahar. After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in October, bin Laden had fled the city, leaving behind the enormous collection. Edwards agreed and drove the tapes up to Williamstown himself.

Most of bin Laden’s tapes were of sermons. One that particularly stood out to Edwards was an audio recording that served as the basis of bin Laden’s 1998 declaration of jihad.

“It was this kind of audacious declaration,” Edwards said. “It really was the kind of point where the global jihad began, in a sense, and in the archive was the audio tape from which that document was taken.”

Other recordings captured bin Laden meeting with young Arabic-speaking recruits, persuading them to join his movement in Afghanistan.

Edwards, who does not speak Arabic himself, brought in a friend, linguistic anthropologist Flagg Miller, to listen to the tapes. Miller listened to the entire collection, an experience he described as “overwhelming” in a 2015 interview with the BBC. Miller later published a book on the collection called The Audacious Ascetic: What the Bin Laden Tapes Reveal About Al-Qa’ida.

Ultimately, Edwards decided that the College should give the bin Laden tapes away. “There was no Arabic department [at the time] and nobody who was going to work on it,” he said. “I thought it really should go to a school with a graduate program in Arabic. So I arranged for it to be given to Yale.”

The original tapes remain at Yale, but Edwards made copies, which are still at the College.

Despite their high-profile provenance, Edwards noted that the tapes — and the rest of the archive — didn’t attract much attention from the Department of Defense, even when bin Laden became a top target for the Bush administration. “Frankly, I don’t think they had the linguistic capacity to deal with it,” he said. “They didn’t have very many Arabists, and they had, I think, one person who spoke any Pashto.”

Still, the thousands of hours of footage provided a window into a particularly tumultuous time in Afghan history. Whitmore emphasized that, despite the political role of the center’s footage, not much has been done to document it. “The Afghan Media Resource Center is a forgotten chapter in media and psychological warfare,” he told the Record.

For Edwards, the most fascinating tape from the original collection featured an interview with a young Mujahideen fighter who had lost his leg. “He was using his prosthetic as a kind of comedy routine,” he said. “His leg was cut off, and he started using his leg as a machine gun — an anti-aircraft gun — and was making this machine gun noise.”

The collection now sits quietly in Dodd Annex, largely untouched. Originals of the archive from Peshawar, and copies of the bin Laden tapes are no longer available online. Meanwhile, the Afghan Media Resource Center’s materials were also duplicated and are housed at the Library of Congress.

“I don’t think many people know about it,” Edwards said. The archive remains a largely untapped resource, waiting for the right students — with the right language skills — to bring his tapes back to life.