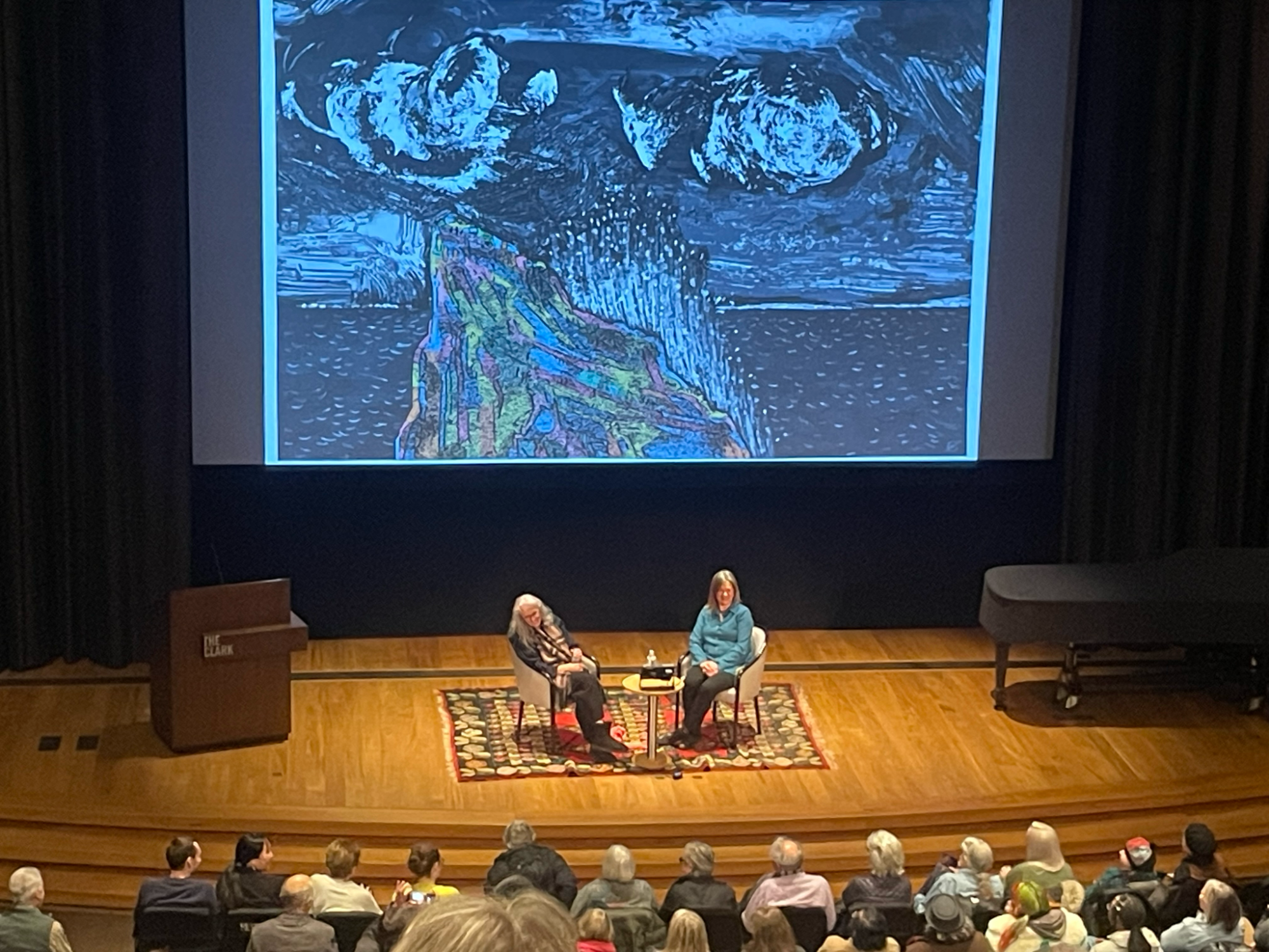

Multidisciplinary artist Kiki Smith visited the Clark Institute of Art last Saturday to discuss her evolving body of work — which spans sculpture, etching, printmaking, photography, drawing, and, most recently, textiles. Her art wrestles with themes of sex, reproduction, mortality, and nature.

Her large-scale tapestry, Seven Seas, was the most recent addition to Wall Power!, a special exhibition on show at the Clark until March 9. The exhibition showcases a collection of contemporary French tapestries on loan from the Mobilier national of France.

Seven Seas features an intricate, multicolored stone cast on a tenebrous ocean with a cloudy sky looming in the background. Smith drew inspiration for the piece from the Apocalypse Tapestry, a set of vibrant medieval tapestries featuring battle scenes between angels and beasts. The imagery in Smith’s own work reflects the detailed folk imagery in the Apocalypse Tapestry, as she often explores the relationship between humans and nature.

In a public interview with Kathleen Morris, the Clark’s director of collections and exhibitions, Smith recalled helping her father, sculptor Tony Smith, assemble geometric shapes for his sculpture projects, an activity that informed her practice of meditating on the same figures for extended periods. “My sister and I would sit after school putting together octahedrons and tetrahedrons, [and] I realized that I work in the same way, but with images,” she said during the lecture.

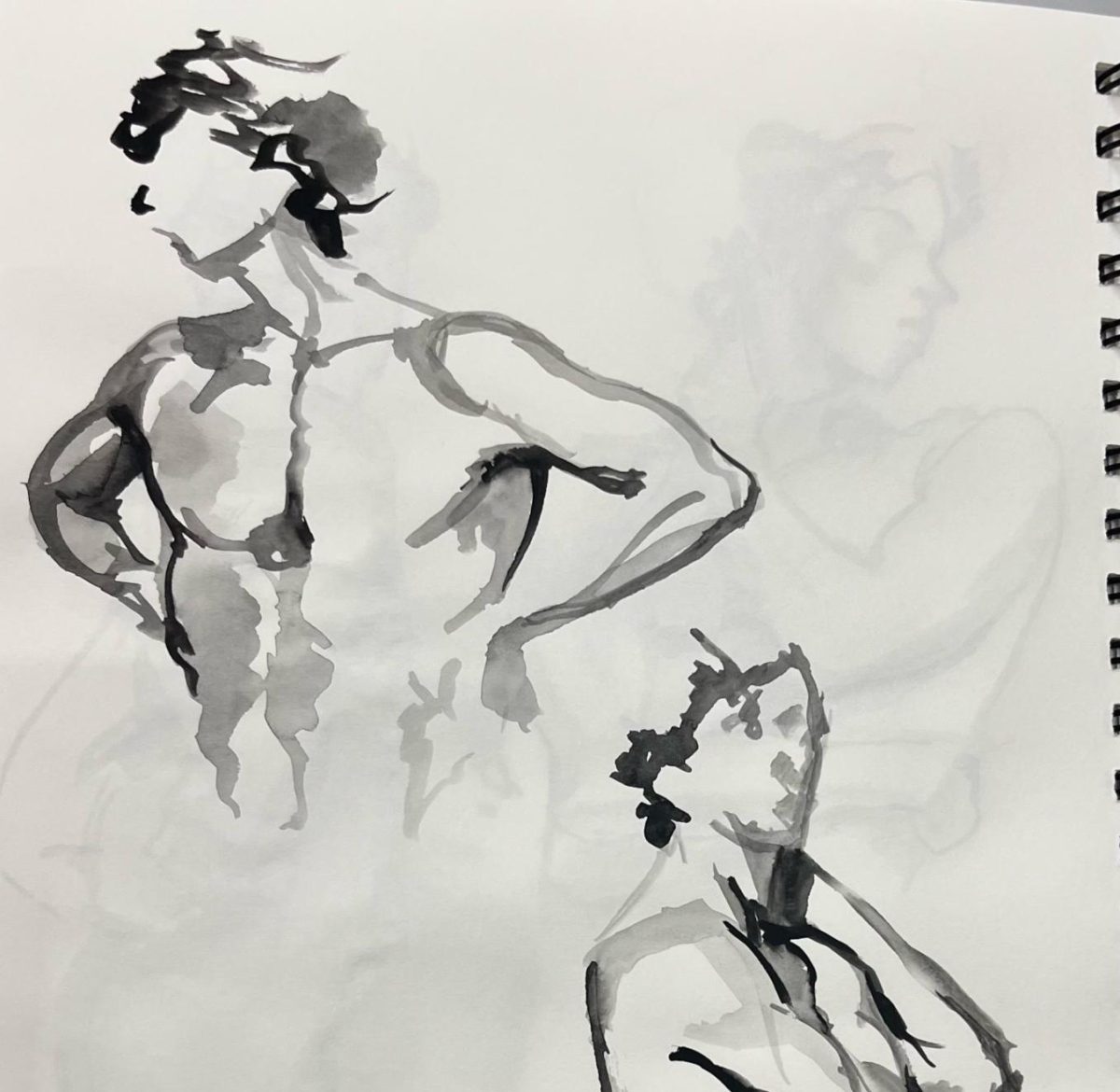

Smith captures her subjects through repetition, using the same mammalian imagery over the decades. “I made these images, and since then, I’ve just used those images over and over again,” she said. She described her recursive technique, first drawing a wolf, then making a sculpture of the same wolf, then re-creating the drawing with a human counterpart, then cutting the drawing up and crafting a collage, and so on.

This process of reconfiguring the same subject across different mediums serves as an opportunity for creative thinking, Smith said. “To me, it’s something very interesting to [move] from two dimensions to three dimensions and back and forth,” she said during the talk. “You can then animate them just by cutting paper or cutting sculpture or something, you can keep animating and having them have different lives.”

Like many of Smith’s pieces, Seven Seas required immense collaboration to create. She sketched the tapestry, but it was woven by a convent of artisans over a period of seven years, during which the finished sections were hidden away from even the weavers themselves. When Smith saw the completed tapestry for the first time, she recalled being surprised by the final product. “The original [design] is a little softer, so I was shocked that I was going to be seen making something so colorful,” she said. “But because it’s a collaboration, you can have a slight distance from it. I was very happy when I went to see it today and it is bold; it’s more like what I would make when I was young.”

Smith said she cherishes collaborations like this one. “Those relationships are extremely important,” she said. “That’s been the greatest joy of my life is working with people, and certainly working with people that know more than I do.”

In Seven Seas, Smith draws inspiration from historical motifs and practices. “There’s so much to learn from history,” she said during the talk. “Being an artist, you have the opportunity to be part of an international world of creativity and appreciate people from other places that are making things, for reasons that you understand or don’t understand,” she said. “Art is a great language because it can go in any direction, and it’s not fixed. It’s constantly being changed and revived and [we’re] rediscovering things like tapestry — crafts that we’ve been pursuing for hundreds and thousands of years.”

Smith encouraged artists in the audience to shed their insecurities and lean into their intuition when creating their own work. “Follow your inner voice,” she said. “Trust what you’re given — trust it really by all your heart — even when it’s a disaster. I mean, I’ve done lots of things in my life that I’m completely embarrassed by.”

Smith said she has found that her work has become increasingly spontaneous as she has matured as an artist. “In my earlier work, I could see how it related personally to my life,” she said. “Now, I just do what occurs to me, and that interest takes me to some other unexpected place. It’s like turning rocks over or showing facets of a whole, just looking at one facet at a time. And I don’t know why I did anything.”

Genevieve Randazzo ’25 took Smith’s encouragement to heart. “I think that what she had to say about no longer feeling so self-conscious due to this genuine interest in the world, is so inspiring to hear as a young person who loves to make art,” she told the Record. “Your perspective is always going to be imbued in the things that you make, but for her it’s this distraction out of yourself and this lavishing of attention onto beautiful things.”

“I like that she wasn’t trying to write [her work] into a pre existing narrative of ‘this is exactly how I thought it was going to go,’” Sylvana Widman ’25 added.

Smith concluded her talk by encouraging the audience to take risks in their creative work. “Who cares if you’re terrible?” she asked. “I draw terribly. I do a million things terribly. But that doesn’t have to stop you. You know, as artists, the stakes of what we’re doing are sometimes really great, and sometimes the stakes are very low. Take any risk that presents itself to you. But, I would be careful with power tools.”