Audre Lorde tells us that poetry gives names to the nameless. W.B. Yeats tells us that poetry is a quarrel with ourselves. And Gwendolyn Brooks tells us that poetry is life distilled. Different interpretations, but perhaps similar implications: What all these poets teach us is that literature has something rather important to say — and we really ought to listen.

As the Trump administration constricts federal arts funding, a local organization has refused to comply with demands, doubling down on its mission to support authors and poets from diverse backgrounds. Founded in 1999 and located only 10 minutes away from the College, the North Adams-based nonprofit Tupelo Press sources and publishes a wide range of literature, including contemporary poetry, poetry in translation, literary nonfiction, and creative nonfiction.

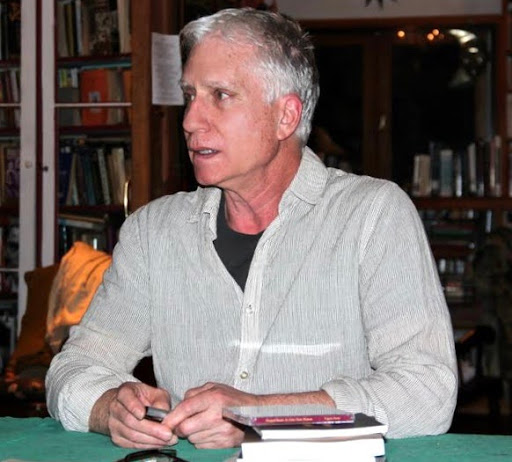

Jeffrey Levine, a poet and Tupelo’s founder, explained that neither genre nor content are strictly prescribed at Tupelo, and inclusivity is the foundation of the press’ mission. “We have always looked to provide a platform for marginalized communities,” he said in an interview with the Record. “We also pride ourselves on giving platforms to emerging writers.”

On Feb. 6, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) — a federal agency that funds arts projects across the country — announced new guidelines barring grant applicants from using federal funds to “operate any programs promoting ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ that violate any discrimination laws” or “promote gender ideology,” referencing a Jan. 25 executive order that states “it is the policy of the United States to recognize two sexes, male and female.”

On Feb. 9, Tupelo released a statement on social media asserting that it would not comply with the new NEA guidelines. “Tupelo Press will not be altering our 25-year mission to promote contemporary poetry and literary prose by emerging and established writers of diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds, including, especially, women and writers of color, as well as the LGBTQ+, immigrant, and Native American communities,” it reads.

“Particularly, as we see the administration dismantling the Bill of Rights, dismantling the First Amendment — telling us what we can publish, and what we can say about what we publish… I don’t see why we would be willing — or any other press would be willing — to kowtow to the administration,” Levine said of Tupelo’s resistance to the NEA guidelines.

For Levine, poetic and political responsibility are inextricably linked. “You see our rights and liberties crumbling, so what is the importance of poetry in this situation?” he asked. “It’s to do what this country is founded upon. We have certain inalienable — or, as the Declaration of Independence puts it, unalienable — rights, and we’re going to exercise them. And if they want to shut us down by cutting off our money, we’ll look elsewhere.”

Throughout its history, Tupelo has been supported by federal grants, but now the press has begun to turn toward private benefactors.

While Levine is confident Tupelo will endure, he worries for the broader literary community and the future of independent publishing. “I don’t think anything having to do with the NEA is a death knell, but it’s very, very sad,” he said. “Many will not survive losing grants. I think we will.”

Levine said political instability might revitalize interest in poetry as a vehicle for resistance. “Every motion produces an equal and opposite motion, right?” he said. “So there’s pushback — I think there will be a growing interest in reading, in poetry.”

He also emphasized that poetry does not exist in isolation — it’s contagious. “I’m not sure that the role of poetry is merely to get a book into somebody’s hands and get it read, but to get a book into your hands and you become changed by it,” he said. “And then the ideas and the sensibility spread throughout the firmament.”

But even 25 years ago, long before the Trump Administration took literary arts to the stockade, the publishing landscape posed challenges for emerging writers.

As Levine was pursuing a master of fine arts at Warren Wilson College in the ’90s, he experienced the difficulties of publication firsthand. “There were dozens and dozens of good writers with no way to get their work into print,” he said.

That need sparked the idea for Tupelo. “I got this bone in my head that there weren’t enough literary presses in the world, and I thought it would be fun to see how it’s done,” he said.

In Nov. 1999, Levine rented a room above the post office in Walpole, N.H., Tupelo’s first office. He set up a landline phone, brought in his typewriter, and began the work of running a nascent literary press. Unlike larger commercial operations, Tupelo has always maintained an “open list” policy, allowing any writer to submit manuscripts for consideration.

From the beginning, this meant quite a bit of work for Levine. He read through thousands of manuscripts — all of which arrived as hard copies through the mail. The decision to find office space above the post office proved to be a good one.

“We had no computer,” he said. “We had no Google. We would announce a contest or an open reading period, and we would be the largest postal client of whatever post office we were at.”

For years, Levine read every submission — almost 5,000 manuscripts each year, by his count. Of those, he would send the best to competition judges and panels.

In 2003, when poet and Robert Frost Medal-winner Eleanor Wilner was serving as a judge for a Tupelo contest, one of the shortlisted manuscripts was Ilya Kaminsky’s Dancing in Odessa. Levine and Wilner realized that Tupelo had struck gold. “Usually, judges take a month,” Levine recalled. “[Wilner] called me after three days. She said, ‘There’s no contest. This has its head and shoulders over anything I’ve read.’”

Dancing in Odessa went on to win the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Metcalf prize, and earn Kaminsky a Whiting Award in 2005. Fourteen years later, Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Kaminsky is only one poet in a lengthy list of critically-acclaimed Tupelo writers. Poet and professor Ruth Ellen Kocher’s domina Un/blued won the press’ Dorset Prize in 2010 and was published there three years later. The publication would go on to win the PEN Open Book Award in 2014. Two years later, Tupelo published New York Times bestselling author Maggie Smith’s 2016 poem Good Bones — a poem that garnered considerable internet fame following Trump’s first election.

Good Bones, which explores parental responsibility and the world’s cruelty, stands as the very kind of resistance Levine said he hopes poetry can — and will — achieve.

“I think that people have extraordinary capabilities, extraordinary capacities, and I’m a meliorist — I believe that things tend to get better over the long run,” Levine said. “Maybe I’m foolish, maybe this is the existential dread we’ve dreaded. I don’t know, but I don’t think so.”

“I think there are enough Americans with a conscience that this won’t hold,” he added. “I have to believe that.”

By Levine’s estimate, poetry may only comprise 1 percent of what is read in America. But it is a crucial 1 percent, he said, one defining our self and national identities.“We poets are cartographers of the soul, cartographers of our national ethos, cartographers of history,” he said.