Usually, whenever former Dean of Admission Philip Smith ’55 got word of a high-profile student applying to the College, he consulted with the College’s president. No prospective student, however, had required Smith to call the director of the CIA until Reza Pahlavi — the Shah of Iran’s son — who attended the College for the 1979-80 academic year.

As Iranians began to protest the U.S.-backed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1977, his son Reza was deciding where to attend college.

While tensions were growing in Iran, President Jimmy Carter invited Prince Reza Pahlavi to come to the United States in 1978. The prince initially attended flight training school at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, according to Smith. However, his family and their security detail thought it best that he attend a rural college so that they could more closely monitor any potential threats. Then-CIA Director Richard Helms ’35 happened to know the Shah personally, given the CIA’s extensive involvement in Iran. They had even gone to the same prep school in Switzerland: Le Rosey.

Helms’ personal connection to the College might have played a role in the Pahlavi family’s decision, according to Magnús Bernhardsson, professor of history and chair of global studies, who specializes in the modern Middle East and advised a thesis written about the Pahlavi family in 2018.

The thesis’ author, Ian Concannon ’18, was fascinated by how a family of international importance interacted with the Williamstown community.

“One of the interesting things about this story is how it continues to remain common knowledge around campus, sort of an urban legend, despite Reza only being enrolled as a student for a year,” Concannon wrote in an email to the Record.

Smith conducted Pahlavi’s admissions interview in August 1979, and recalled how Pahlavi arrived with a motorcade of three limousines and multiple Iranian generals. “Reza was nervous as can be,” Smith said in an interview with the Record.

“What do you really want to do?” Smith asked Pahlavi.

“I want to meet some people my age,” Pahlavi said.

Smith made arrangements to fast-track Pahlavi’s application so he could begin attending classes that fall as a first-year. He took a variety of classes, including international relations, geology, and a new course on Islamic law.

“My understanding was that the College brought in somebody to teach a course on Islam for him,” Smith said.

In September 1979, Pahlavi’s mother and three siblings joined him in Williamstown, where the entire family lived in a home on South Street, across from the Clark Art Institute, until 1984. Due to security concerns, Pahlavi stayed in the family’s home instead of College dorms, though he was still a member of Williams Hall’s F entry, Smith said.

Pahlavi’s older sister attended Bennington College, while his younger brother attended Mount Greylock Regional School, and his younger sister attended Pine Cobble School.

Bernhardsson said the family kept a low profile in the Town. “They did not want to attract attention to themselves, and I am not aware of them organizing or hosting high profile events,” he said. “They kept to themselves, though they were active at the local Pine Cobble School.”

The Shah himself did not live in the Town because he was continuously denied entry to the United States until he was hospitalized for cancer treatment in October 1979. He died of the disease the following July in Cairo, Egypt.

After his father’s death, Pahlavi chose not to return to the College for a second year. Instead, he went to Egypt to assume the title of the Shah of Iran in exile, the Record reported on Sept. 16, 1980.

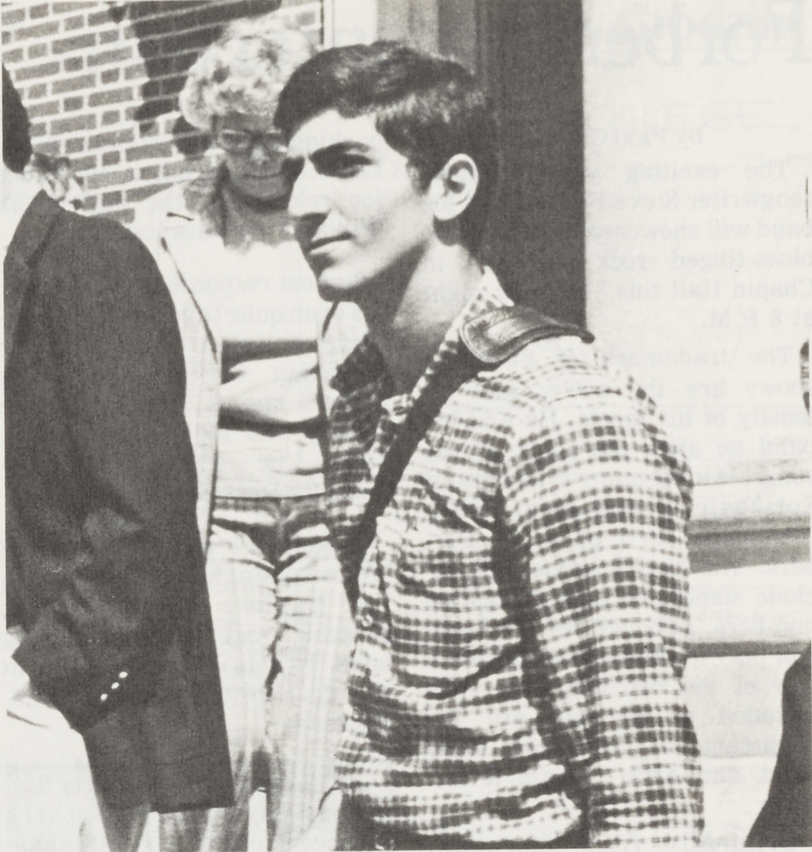

During his time at the College, Pahlavi was a dedicated student who tried to blend in with the rest of the student body. “Most people think he’s just another student here,” Irve Dell ’83 told the Record at the time. “The only unusual thing is that you always see his bodyguards, but you get used to that.”

Students only complained about the security detail when Pahlavi showed up to a water fight between Williams Hall and Sage Hall with the security detail, Smith said.

Two of Pahlavi’s bodyguards — named Pat and Mike, as Smith remembers — were former New York City police officers. When Pahlavi visited Smith at the admissions building, he would occasionally sneak out the back door in order to briefly escape their close supervision.

Pahlavi’s relationship to his guards, however, ran deeper than his desire for momentary independence. In 2004, when he visited the College for a two-day trip organized by Bernhardsson, Pahlavi remembered the connections he had made. “When Reza came, he asked to see his former security detail,” Bernhardsson said.

During his visit, Pahlavi gave a talk to a packed Brooks-Rogers Auditorium titled “Iran: Past, Present, Future,” according to an itinerary Bernhardsson provided to the Record. He also met with students, gave an interview to local press, and visited a class.

“It’s an interesting story that captures a strange ending of a regime that started after World War I as a modernizing regime, that would then end in Williamstown — a bizarre epilogue to that story,” Bernhardsson said.