For most, the world’s remaining glaciers take on a mythical character: They are symbols of extreme, unknowable natural power. But, for Assistant Professor of Art Ohan Breiding, the Rhône glacier, situated high in the Alps of their native Switzerland, represents something more personal: a site of mourning. “Belly of a Glacier“, Breiding’s exhibition, jointly curated by MASS MoCA Senior Curator Susan Cross and WCMA Deputy Director Lisa Dorian, is a multimedia depiction of pain and sorrow about the predicted loss of the Rhône glacier. The show opened Feb. 1 at MASS MoCA.

The exhibition’s main feature is a 33-minute short film, which begins with a look into Breiding’s early years in Switzerland. “It starts with one of my childhood memories of catching a snowflake, thinking it’s so beautiful, perfectly symmetrical, and then thinking about the mathematics of a snowflake — a product of nature,” they said. “And because it’s so beautiful, I want to gift it to my mother. So it almost starts with spirituality, or this sense [that] there’s a spirit in the work.” During the film, as a young Breiding carries the snowflake, it melts in their hands, foreshadowing the glacier’s destruction.

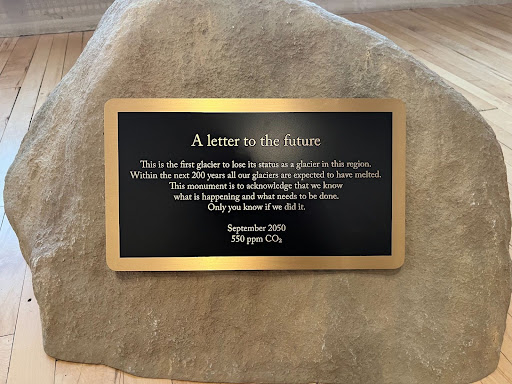

The exhibition centers feelings of loss, with close-up shots of the glacier adding a personal element to the grief, as if a living creature were dying, Breiding said. In 2019, a group of approximately 100 people, including former Prime Minister of Iceland Katrín Jakobsdóttir, held the first recorded funeral for a glacier. The ceremony culminated in the mounting of a plaque inscribed with a matter-of-fact “letter to the future,” which served as the inspiration for a similar plaque in “Belly of a Glacier”.

After the childhood memory, the film explores creation. “And then we come to a birthing scene,” Breiding explained. “I was really interested in thinking about the word ‘calving.’ ‘Calving’ is for the mother calf to give birth to a calf, but in glaciologists terms, it’s about the death of a glacier, about the breaking off of a big iceberg into a glacial lake, or an ocean.”

For Breiding, there is power in how language represents glaciers. “The way we describe a glacier is deeply linked to how we would describe an animal,” they said. “For me, that felt like an invitation to listen more closely to what the ice has to say.” The linguistic and aural association between the birth of a cow and the splitting of a glacier also evokes natural patterns. “Birth and death are cyclical and become the same thing,” Breiding said.

Sound designer Richie Carey highlights the connection between living and non-living natural phenomena by pairing geological scenes of glacial expeditions with sounds from the womb, and overlaying the visceral scenes of the calf birth with the rumbling of a calving glacier.

Breiding’s undertaking is notably interdisciplinary, involving collaboration between artists and climate scientists at the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility. Breiding cites care as a common characteristic of those involved in the project. “The people who work [at the Ice Core Facility] call themselves curators, and, from Latin, curator means to take care,” Breiding said. “I was really interested in thinking about these people who were obviously working in the sciences, but then also had a responsibility to take care of this ice.”

Breiding’s aesthetic choices engender strong emotions, with red-tinted archival film of Rhône glacier expeditions interspersing the film. “The red, in a way, comes in as a warning sign, as a fever, as blood,” they explained. “But it also could be seen as love or dependency or urgency or passion.” Breiding’s work hinges on this balance of love and anxiety. “It’s always about this friction between what we’re losing and what we’re loving at all times,” Breiding said.

Breiding leverages the physical space of MASS MoCA to convey the dissonant emotions associated with climate change. The bronze plaque and photographic installation stand in an otherwise open gallery, encouraging the viewer to walk around the room as they take in the exhibit. The film itself is screened in a dark room where the audience is invited to sit on boxes that were used to transport ice cores from glaciers. A narrow corridor lined with postcards from the glacier’s visitors connects the two spaces.

“I think most of us are very aware that we’re living in a place of complete political upheaval and urgency, and the corridor becomes that space where we’re not in one room seeing the photographs, or in the other room seeing the film, or walking between the two,” Breiding said. “And while we’re walking between the two, we’re invited to look at these very intimate — but almost banal drawings — that I made of postcards I collected that were sent from the Rhône region.”

The transitory nature of the hallway segment of Breiding’s exhibition reflects the instability of ice. The transition from solid to liquid jeopardizes the collection of information preserved in the Rhône glacier’s ice, and yet is an innate quality of any glacier. “The word Rhône means to flow or to flee,” they explained. “So even thinking about water as something that’s migratory or how this water, on a molecular level, is already existing in other places.” Delaying entropy is no simple feat but, given the stakes of climate change, Breiding is not deterred.

“For me, this work very much feels like I’m creating an archive for the future,” Breiding said. “We’ve never experienced [these changes] as humans. We’ve never experienced a loss of something that’s so ancient within our short lifetimes, and so it’s about what our feelings are doing and the loss that’s deeply inside of us, and what we’re going to do with that loss.”

While centering grief, Breiding’s film also emphasizes beauty: Sweeping views of the Swiss Alps come after careful shots of studied glacial cores. “I think we’re mourning what we’re used to being a part of,” Breiding said. “But nature knows how to regenerate.”

“Belly of a Glacier” will be on display at MASS MoCA until Dec. 14.