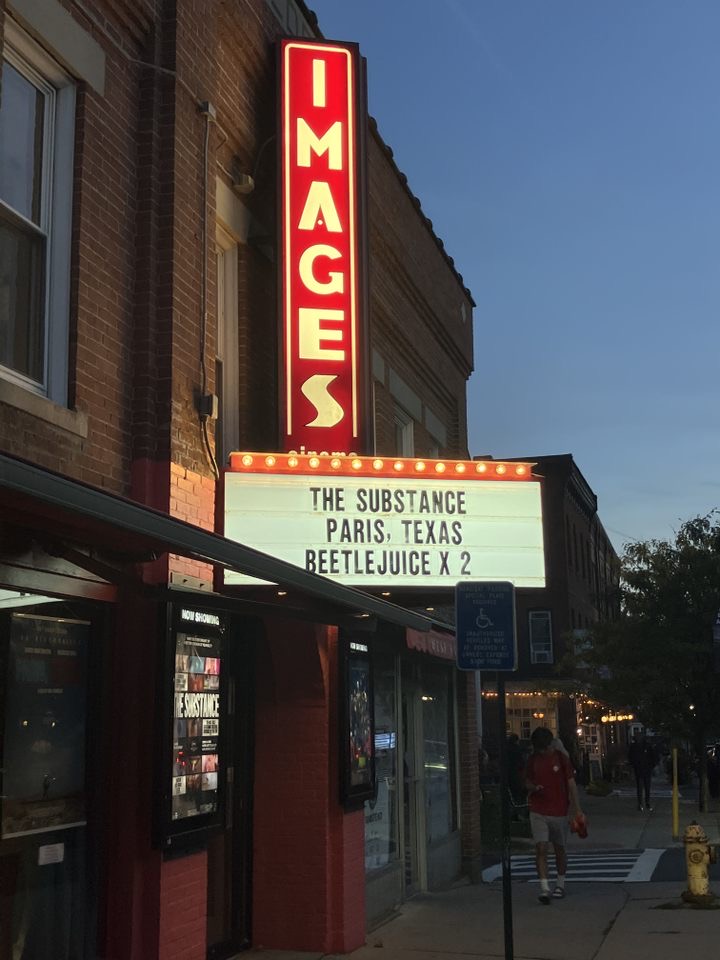

“Remember you are one,” says the dominating, faceless figure that penetrates the mind — or minds — of Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), the protagonist of The Substance, which will have its final showing at Images Cinema tonight at 7 p.m. Written and directed by French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat, the film follows Elisabeth and the physical manifestation of her alter ego. This visceral, gruesome, and elegantly repulsive alter ego exposes the psychologically convoluted perception of the female body portrayed in The Substance.

The story follows Elisabeth, a once-acclaimed actress who is fired from her job as the host of an aerobics TV show on her 50th birthday. After a car accident, Elisabeth is hospitalized, and a nurse recommends an injectable substance intended to create a “younger, more beautiful, more perfect” version of herself, as the enigmatic voice which haunts the film tells her over the phone. The catch, however, is that her middle-aged self does not just disappear: Both halves of her fractured identity coexist. While one is activated, the other must lie unconscious for seven days.

Elisabeth’s “more perfect” self laments her wrinkles and cellulite in the mirror, hosts a show whose target audience is women who hate their bodies, and is bossed around by a man in a suit who eats with his mouth open. It seems like a straightforward story with a lesson told many times before. I thought so too — for the first half of the film, at least.

As Elisabeth continues to live two split lives — one as a newly successful young actress who goes by Sue (Margaret Qualley), the other as an aging Hollywood has-been — her two selves develop resentment for each other, prompting Elisabeth to attempt to extend her stay in her younger form for more than a week. But the consequences, she quickly learns, are increasingly severe, and the plot becomes more and more bizarre: Sue and Elisabeth start sabotaging each other’s sex lives and careers as the sequences blend fantasy and reality.

These plot shifts are mirrored in the editing throughout the movie. As Elisabeth’s parallel lives grow increasingly distinct, the colors, music, and pacing do as well. By the film’s end, the tension created by the over-the-top editing and gory visuals render the first half unrecognizable.

Body horror pervades the film. After all, Elisabeth is horrified by her own image. There is no shortage of needles and blood, and while some critics have taken this as a sign of oversimplification or exaggeration of feminine self-image, I’d argue they were necessary artistic choices to represent the literal and figurative creation of a new self.

The kind of body modification that Fargeat gestures at throughout the film is commonplace in our society, even at the most basic level: Many of us, for instance, wear sunscreen religiously. There are plenty of good reasons to do so, but I would argue that most of us do it because we are — at some level — horrified by spots and wrinkles, a fear Fargeat evidently wants us to reconsider.

The Substance won Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival in May. With this film, Fargeat was able to join the canon of French filmmakers who have recently achieved critical and commercial success. Many of these filmmakers — such as Justine Triet (Anatomy of Fall) and Céline Sciamma (Portrait of a Lady on Fire) — explore different facets of womanhood in their work, from the most tender and sacred to the most complex and afflicting ones, the latter of which The Substance explores.

Halfway through the film, Elisabeth washes her hands violently, à la Lady Macbeth, when she realizes that all of the pain she has endured is impossible to scrub away. In this way, The Substance wants audiences to avoid having to wash their bloodied hands only to realize that the blood is their own, just as Elisabeth stares begrudgingly at the billboard with Sue outside her window, unable to recognize herself.