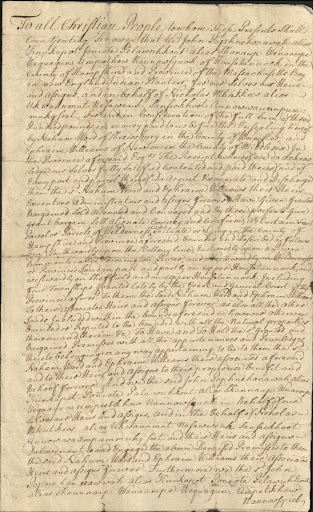

The father of Williams College’s founder, Ephraim Williams Sr., played a direct role in the displacement of the Stockbridge-Munsee Tribe from the Town. Documented in a 1737 deed, Williams Sr. claimed land that was already the home to Mohicans.

In interviews with the Record, however, multiple students said that the College has been slow to enact recommendations proposed by a variety of working groups seeking to improve the College’s relations with Indigenous people.

“There isn’t a question about what the campus should be doing — it’s already outlined,” said Daisy Rosalez ’25, a leader for the Native American Indigenous Students Alliance (NISA).

In 2021, the College’s Committee on Diversity and Community published a report entitled “Recommendations for Reckoning with Our Institutional Histories.” The recommendations were meant to “to better represent and reckon with the College’s histories, and where needed, repair relationships with community members.”

One of the recommendations, “to create a committee, or committees, which directly address particular problematic histories; for instance, having a committee that reckons specifically with Indigenous displacement,” led to the creation of the Native American and Indigenous Working Group. The College also published an official land acknowledgment, per another one of the committee’s recommendations.

Later that year, Mirabai Dyson ’24, Gwyn Chilcoat ’24, Hikaru Hayakawa ’24, and Jayden Jogwe ’25 drafted a list of recommendations in their independent study that called upon the College to provide reparations to the Mohican Nation and create free housing for members of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community. The Native American and Indigenous Working group has since added to the students’ list of recommendations.

“Nothing has happened,” Jogwe said. “[The College] created the working group as a kind of way to stall us or make us do the labor ourselves.”

The four students also worked with the Williams Office of Communications to place signage across the College that reads “Kpomthe’nã Mã’eekanik: We are walking on the lands of the Mohican.”

Dyson argued in a Record op-ed in 2022, however, that land acknowledgments on their own are not enough. Dyson suggested two specific changes that the College could make beyond land acknowledgments. She called for the College to invest “in the creation of a Native American and Indigenous studies department” and “to do more admissions outreach to Native American and Indigenous high school students,” since no members of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community have attended the College.

“The College has a responsibility to be more proactive about trying to understand and fill any of the needs [of] the Stockbridge-Munsee Community, because it has been mostly individuals and small groups at the College that have been doing this work,” Jogwe said.

Rosalez echoed this sentiment, adding that she feels as though the College places the burden of labor on its Indigenous students.

“This individual work — which often falls on Indigenous students — comes at a cost,” Rosalez said. “Students that are here are struggling with having to make a decision: How much effort should they be putting towards their academics [versus] sacrificing their academics in an effort to attempt to make institutional change?”

“Unless the institution really, really puts some effort in supporting the needs of student groups, then the change they’re expecting from [them] is coming at an alarming high cost — the mental health cost,” she added.

Students founded NISA in spring 2022, and according to Rosalez, its infancy has created roadblocks in its advocacy work — especially when the campus expects the group to carry the weight of all Indigenous organizing at the College.

“Within our student group, we’re getting to know each other’s community,” Rosalez said. “It’s hard because we’re trying to figure out who we are.”

In Rosalez’s opinion, the College could support NISA and Indigenous students by employing more Indigenous faculty and staff. “I think the biggest thing that would help [NISA] is having a Native liaison, having Native faculty, having some kind of representation, someone to go to on this campus whose job it is to help support us,” Rosalez said.

But the lack of a faculty liaison, Rosalez added, is only part of the problem. She said that NISA only has nine members, one of whom is studying abroad, and none of whom are first-years, raising real concerns about the sustainability of the group in future years.

Dyson said she hopes the needs of Indigenous students are also met at other institutions of higher education. “I think it’s easy with having these conversations to fall into a trap of letting it end with Williams,” Dyson said. “Obviously, yes, I would love to see more representation of the Stockbridge-Munsee tribe at Williams. But at the end of the day, it goes far beyond Williams.”

Rosalez said that College can and should outsource help to create the changes she and other students are calling for. “[Institutional change] does demand learning and understanding and coming face to face with our schools past — and not just our schools past, but our society’s past — with genocide,” Rosalez said. “[The College doesn’t] have to do it alone. They can bring in experts, they can bring in the people who can help push this forward.”

[Editor’s note: Dyson and Jogwe were both interns at the Stockbridge-Munsee Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Their opinions are their own and are not a reflection of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community.]