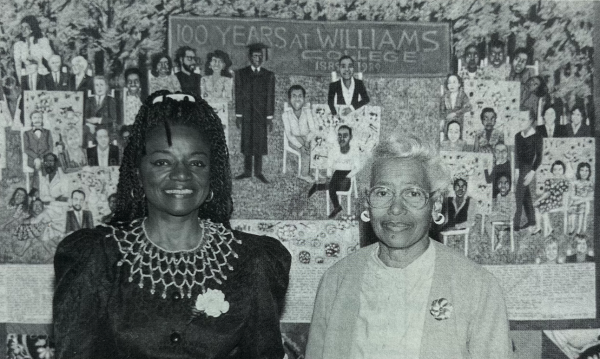

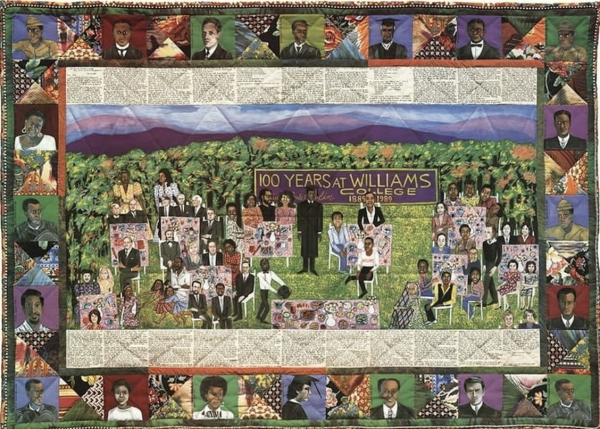

Faith Ringgold, a renowned multimedia artist and author, died on April 12 at the age of 93. Ringgold was most famously known for her signature pictorial “story quilts” that often addressed issues of race, gender, class, and family. Ringgold’s quilt, “100 Years at Williams College 1889-1989” — which was commissioned for the 100th anniversary of the graduation of the College’s first known Black graduate, Gaius C. Bolin, Class of 1889 — will soon be installed at the newly-renovated Davis Center. Faculty and staff at the College remember Ringgold as a trailblazing artist whose quilt serves as a powerful symbol of the College’s history.

Ringgold was born in Harlem, N.Y., in 1930 and began making art in her early childhood. She started her professional career as a landscape painter and eventually transitioned to making textiles, including the award-winning “Tar Beach,” which later gave rise to her first children’s book of the same name.

Ringgold’s works often contain references to political issues as well as traditional African and African American styles and techniques. Her profile as an artist and influential figure grew during the Civil Rights Movement with her series of murals “American People,” which includes the well-known works “The Flag is Bleeding,” “US Postage Commemorating the Advent of Black Power,” and “Die,” all of which explore the legacy of racism in the United States.

“I think that working with cloth had two meanings for her,” said Professor of Art, Emerita, Eva Grudin, who spearheaded the process of commissioning the quilt. “One was certainly to keep allegiance with her African American past — her mother was a seamstress, there were quilters in the family. But [it was] also a feminist statement because the Black arts movement happened just as women’s [liberation] was coming to the fore. Elevating cloth to storytelling, elevating women’s art that is dismissed to high art, was part of her goal.”

“Her quilts incorporate history, textiles, and visuals into telling institutional stories,” said Jessika Drmacich, Special Collections records manager and digital resources archivist.

Grudin and the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) reached out to Ringgold in 1989 to commission the quilt as part of a larger exhibition of African American art that Grudin was curating for the museum. Grudin, who taught courses on African American art and the Harlem Renaissance at the College, immediately thought of Ringgold when curating artists for her exhibition. “I thought of not just Faith but her whole conception of storytelling,” she said.

Dean of the Faculty John Reichert, as well as WCMA Director Tom Krens and Senior Curator Deborah Rothschild, were supportive in the process of making space for the exhibition and commissioning Ringgold, Grudin said.

Initially, however, Ringgold was hesitant to take on the project, according to an article Grudin wrote in the Winter 1990 edition of the Williams Alumni Review. “Williams is a long way from home for me,” the Harlem-based artist said in the article. “It’s a far reach … but how else, other than by stretching, can an artist grow? I’ll try it.”

Along with extensive research that Grudin conducted, Ringgold read histories of the College, newspaper articles, and pamphlets, and interviewed both students and Town residents for the project, which took just under a year to complete. The project involved constant correspondence and collaboration between the two as Ringgold worked on the quilt from 1988 until the opening of the exhibit at WCMA in April 1989.

During this time, Grudin got to know Ringgold, and reflected on the artist’s personality in an interview with the Record. She told the story of Ringgold taking her to a movie theater in Atlanta to see a festival of films by director Spike Lee. The crowd, Grudin said, was talkative and more immersed in the experience than she was used to. “It was so much fun,” she said. “Faith was so delighted by my delight in being exposed to something new that nobody had ever told me about.”

Grudin described Ringgold as self-motivated and passionate when it came to making the quilt. “I don’t think I directed her in any one specific direction… She got so into it,” Grudin said. “She was so curious, so joyous, enjoying the involvement, enjoying the stories, but not shirking the history. She made it as three dimensional as possible.”

The resulting quit has become a “hallmark in the museum’s collection,” said WCMA’s Deputy Director for Curatorial Engagement Lisa Dorin.

Two long panels on the quilt depict the story of Francie, a fictional alum of the College, who is discussing the challenges faced by Black students at the College. Her story references multiple student activist movements at the College, including the successful 1969 student occupation of Hopkins Hall to demand the creation of the Africana Studies program and a similar occupation in 1988 of Jenness House, which led to the establishment of the Davis Center, known as the Multicultural Center at the time.

The central image is of a picnic featuring many prominent people in the College’s past, including several College presidents as well as renowned poet Sterling A. Brown, Class of 1922; Gargoyle Society president and star football player George Montgomery Chadwell, Class of 1900; and Davis Center namesakes W. Allison Davis, Class of 1924 and John A. Davis ’33. Bolin is dressed in a cap and gown in the center of the tapestry, presiding over the scene.

In the quilt, according to a diagram that accompanies it in the Alumni Review article, Ringgold also included people like Abraham Parsons, a staff member at the College in the late 1800s who was reportedly the victim of widespread abuse by white students; Donna Lindsay ’75, an early Black, female graduate of the College; Margaret Hart, a descendant of a Black family that had lived in Williamstown for generations; and both Ringgold and Grudin themselves.

Both Drmacich and Grudin noted that Ringgold took care to highlight people who had been overlooked in traditional histories of the College. “One of the special contributions of ‘her’ quilt is that, long overdue, it makes public the private role local Black families, like the Harts, played in sustaining our black student body,” Grudin wrote in the Alumni Review.

“I think that Ringgold wanted questions to be asked,” Drmacich said. “Seeing them all having a picnic and be seated side by side … my interpretation is Ringgold wanted us to think about relationships between the administration and people’s experiences, and how they all interact with each other to have these complex stories that we need to investigate and how this tapestry is something we can grow from.”

The quilt originally hung in the old Sawyer library building and was moved to Schow library when the current Sawyer building was constructed in 2016, where it currently remains. “Because of its large size and its importance to college history, it has most often been on permanent view outside the museum,” Dorin said. The College plans to move the quilt to the Davis Center, which Dorin said was the result of collaboration between WCMA, the Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and Davis Center leadership. Doren said that a timeline for the move has not yet been finalized.

“It’s a fantastic and rightful location for it,” Drmacich said. “I think it could be much more integrated into the wonderful narrative of the College campus and history.”

Grudin agreed, noting that she was disappointed with the lack of attention the quilt has received since it was first put on display. “A lot of people have never seen it who should have seen it,” she said.

“I think there’s a whole history here of support and abandonment,” she said of the College’s initial attitude to the exhibit compared to the quilt’s later placement in Sawyer and Schow, which she said she thought contributed to its lack of popularity. “The time has come for it to really have the prominence it deserves.”

Ringgold passed during this year’s Bolin Legacy Mentorship Weekend, intended to honor Bolin and other alums whose contributions have been historically overlooked. The coincidence of these two events evoked Grudin’s prediction from her 1990 article: “Years from now when the Bolin celebration is long forgotten and the issues of the last 100 years a thing of the distant past, we will have this work of art to jog our memories.” Bolin Weekend continues to this day, and the quilt serves not only to represent the College’s past but also Ringgold’s memory and her contribution to the College.