“If I can get annoyingly ‘Williams’ about it, I think my experience of the Williams Anti-Apartheid Coalition [(WAAC)] has shaped my whole life,” said Andy Levin ’83, who was a U.S. Rep. from Michigan’s 9th Congressional district from 2019 to 2023, in an interview with the Record.

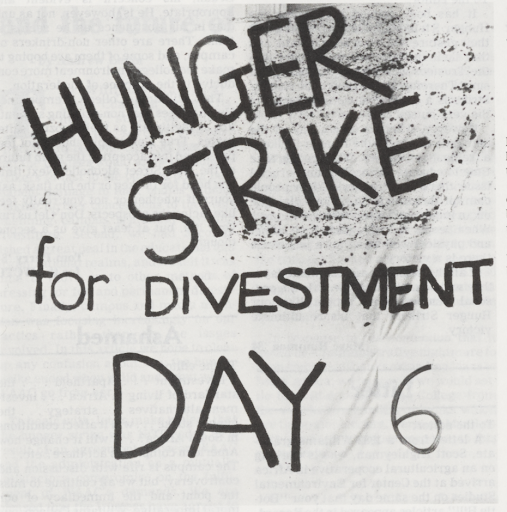

In January 1983, Levin and fellow activists — including Derede Arthur ’83, Eric Fernald ’83, Stephen Sowle ’83, and Navjeet Bal ’84 — organized a hunger strike, seeking to pressure the College to divest from its holdings in companies with ties to South Africa. At that time, South Africa was an apartheid state and not in compliance with the Sullivan principles, a code of conduct used to assess corporate social responsibility by Americans pushing for divestment. WAAC deemed 15 companies which the College’s endowment was invested to be in violation of these principles and, after demanding that the College act immediately to partially divest, began the hunger strike on Jan. 21, 1983.

While WAAC and other supporters of divestment believed that the College could put economic pressure on South Africa by changing its investments, administrators maintained that they had to consider the practicality of such investments — which could have entailed divesting from profitable companies with minimal activities in South Africa. When asked whether he was concerned for the health of the strikers — who had fasted for six days — then-President of the College John Chandler responded that he was “also concerned for the health of the institution,” and that “it would be a loss if the College acceded to tactics of this kind,” the Record reported in February 1983. Although the Advisory Committee on Shareholder Responsibility (ACSR) — a committee formed in 1978 amid the anti-apartheid movement — began a review of four of the 15 companies listed following the strikers’ proposal, the College never met WAAC’s demand of selling its $6 million in shares of these companies out of its then-$140 million endowment.

In 1986, then-President of the College Francis Oakley wrote in a statement that the College’s policy on shareholder activism was “to use its prerogatives as a shareholder to urge the companies whose stock it holds to withdraw from South Africa,” the Record reported, rather than selling its stock in companies not aligned with the Sullivan principles.

Although the College did not meet Levin and the other strikers’ demands, Levin said that his time as an activist at the College would be instructive for the rest of his life, including in his advocacy for Palestinian rights in the U.S. House of Representatives.

“I feel like there’s a throughline [from] my anti-apartheid activism in college directly to my activism on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” Levin said.

He introduced the Two-State Solution Act in the House of Representatives in September 2021, which did not make it to a vote. The act proposed limiting the United States’ ability to provide security assistance to Israel and prohibiting the United States from providing support for projects in areas that came under Israeli control after June 5, 1967. In the wake of the legislative action, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and EMILY’s List spent more than $4 million and $3 million to support Levin’s opponent, he said, and he lost in the 2022 Michigan primary race to now-Rep. Haley Stevens.

Despite the fallout, Levin said he does not regret introducing the bill. “I feel like the most valuable things in my life are times [when] I took risks … [when I decided] this is the right thing to do,” he said. “This is who I am.”

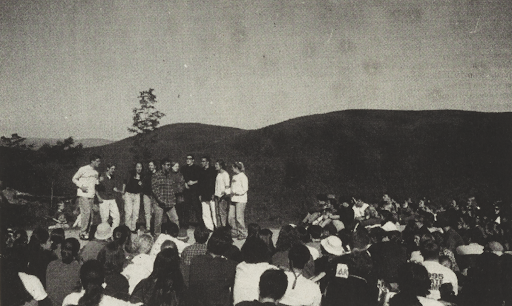

According to Levin, one such moment was when he and 150 other students packed into a meeting with the College’s Board of Trustees in January 1983. The trustees had allowed WAAC to present six spokespeople to submit its divestment proposal, but the group wanted the meeting to be public, Levin said. Instead, according to Levin, the trustees held the meeting in a small conference room in Hopkins Hall with “a conference table that seated, like, 12 people,” he said. The entire group filled the room, and according to Chandler in January 1983, “The trustees were frustrated, annoyed, and even angry in the hot, uncomfortable room jammed full of people.”

One of the trustees approached Levin afterward and told him that he was a bad person because he was dishonest about the number of people attending the meeting, Levin recalled.

“I was shaking in my boots,” Levin said. “It’s sort of a badge of honor. But also let’s admit our feelings, right? I mean, it’s hard for people to yell at you.”

Ultimately, WAAC ended the strike out of concern for the physical health of the participating students and because they felt they “had accomplished a great deal in the educational and organizational realms,” Levin said in a February 1983 op-ed. Arthur, one of the six students who participated in the hunger strike, told the Record that they also ended the strike out of a desire to protect faculty members who had supported the movement. “We were afraid that, because of us, faculty members would lose their jobs,” she said, adding that “the university and the administrators turned on the faculty.”

Advocacy for divestment has occurred over the 40 years since WAAC protested the College’s investments, most recently regarding the ongoing war in Gaza and the climate crisis. On Feb. 8, the student group Jews For Justice met with ACSR to discuss divestment from weapons manufacturing. Levin was careful to draw a distinction, however, between the latest calls for the College’s divestment from manufacturers of Israeli weapons and other movements for divestment. “I mean, this particular issue gets very hard, right?” he said. “Because it’s different from apartheid in South Africa, and it’s different from climate change.” He continued that fighting Islamophobia and fighting antisemitism are both really important, and “it’s so important for us all to be in solidarity with each other about all these hatreds. But if we want to do that, we have to say, ‘Well, I like to criticize my government … [and] I better be able to.’”

Arthur, now a senior lecturer in the writing program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, has been active in the university’s fossil fuel divestment movement — which she, too, credits to her experience as an activist at Williams. “Universities in general socialize students to think [they] have no power,” she said. “[But] at a small school like Williams, there’s leverage that students have, [as] there’s only 2,200 of you.”

Sowle, another former WAAC activist and Levin’s first-year roommate, reminisced in 2015 about his experience as an activist at the College for a research paper. “Williams is an interesting place,” he said in the paper. “You can go toe to toe with people and be sitting down having a beer with them the next day.”

“The whole place teaches you to hone your arguments, [and] hopefully, to actually listen to other people’s arguments,” Levin said. “The fundamental lessons of a liberal arts education require us to struggle for justice, require us to smash out of the bounds of our books and into the messy world around us and engage.”