“No one knows what Bernie and I do, except for Bernie and I,” Campus Recycling Coordinator Colin Moran told the Record. Alongside Campus Recycler Bernie Baker, Moran works daily to collect, sort, and prepare the campus’ recycling for pickup by Casella Waste Systems, the company that transports and processes the College’s recycling.

The College contracts Casella for roughly $40,000 every year to process its recyclable waste, Custodial Manager Ricky Harrington wrote in an email to the Record.

To investigate the efficacy of the College’s recycling system, the Record spoke to the Zilkha Center, trailed the work of custodial staff, and surveyed students. The anonymous survey, which was conducted last week, was sent to 500 randomly selected students and garnered 144 responses. While respondents said they care about recycling and believe that they are recycling their own waste effectively, they also reported confusion about the College’s recycling program and estimated that recycled waste produced by students is generally contaminated. A lack of student compliance leaves Baker, Moran, and other staff members to pick up the slack, according to a series of interviews with custodial staff.

Comparing the numbers

“The College enjoys the reputation of being sustainable,” Moran said. His assertion proves true by several assessments of waste production.

Since 2019, the College has partnered with the Post Landfill Action Network (PLAN), whose Atlas Zero Waste assessment has been used by roughly 50 institutions across the country, to assess its progress in reaching a zero-waste campus.

After failing to reach a medal certification by PLAN during the 2019-20 academic year, the College formed the Zero Waste Action Planning Group in May 2022, which produced the Zero Waste Action Plan — a detailed document that outlines a series of actionable steps to create a zero-waste campus.

Beginning in March 2023, Zilkha Center Zero Waste Interns Brian Lavinio ’24 and Saumya Shinde ’26 produced another zero-waste assessment, which was released in November 2023. That year, the College received a “bronze” ranking by PLAN for its waste reduction efforts, with an “Atlas Zero Waste Achievement Level” above that of peer institutions like Colby and Wesleyan.

In the report, the College scored 35 out of 42 possible points on PLAN’s assessment, which measured how the College facilitates recycling with measures such as bin standardization and signage. The Atlas assessment, however, does not focus on studying the lifecycle of items purchased or brought to campus by students independently, which make up a substantial portion of campus waste, as the report acknowledges. Lavinio believes that, despite this limitation, the study accounts for student-purchase waste by looking at the quality of public recycling bins, he wrote to the Record.

The Zilkha Center and custodial staff independently collect data on the amount and type of waste produced at the College, which paints a clearer picture of the proportion of material waste from the College that is recycled.

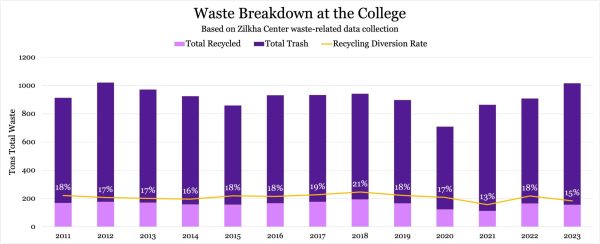

The College’s diversion rate — calculated by dividing tons of recycled waste by the total waste, which comprises both recycling and trash — has remained fairly consistent since the Zilkha Center and facilities workers started collecting the data in 2011. (This diversion rate, calculated by the Record, excludes compost, while the Zilkha center’s diversion rates often include both compost and recycling.) The diversion rate dipped in 2021, which Deputy Director of the Zilkha Center Mike Evans believes was because the pandemic prompted the use of more single-use plastic, he wrote to the Record.

Since 2011, the College has produced on average 754.0 tons of trash and 160.7 tons of recycling per year, meaning it has diverted on average 17.4 percent of potential trash to recycling. The College’s recycling diversion rate and amount of waste production fairs akin to or worse than peer institutions. In 2018, Amherst College diverted 18.6 percent of its total waste (excluding compost) through recycling, according to the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System. The same year, Connecticut College diverted 40.2 percent of its waste to recycling, while producing only 629.91 tons of total waste, and Middlebury diverted 60.4 percent of waste to recycling in 2022.

As Evans noted in his interview with the Record, recycling is just one aspect of the College’s broader zero-waste goal, and increasing diversion rates of waste does not necessarily reduce total waste production. Still, recycling remains an important part of the College’s waste-reduction plan, and data from other NESCAC schools show that it’s possible to both decrease waste production and increase recycling diversion rates.

Tracking recyclables

Casella picks up the College’s recycling from the Facilities Center on Stetson Road roughly once a week and hauls it to Rutland, Vt. Before pickup, it’s up to students, custodians, and finally Baker and Moran to sort and prepare recyclables, Moran said.

Although Moran said that the quality of recycling differs between dormitories, the College’s custodial staff is used to dealing with students’ poorly sorted recycling, which results in contamination of recycling bins, Custodial Manager Rickey Harrington told the Record.

“Contamination is always an ongoing battle,” he said. “Custodians help with this process. If the custodial staff sees contamination, and if there’s a lot of it, it ends up going in the trash.”

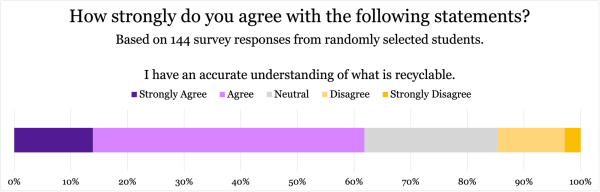

A Record survey found that students believe they have a personal understanding of and a commitment to recycling but also that their peers do a poor job recycling. 62.1 percent of respondents reported that they “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement “I have an accurate understanding of what is recyclable.” When students were asked how often they determine if an item is recyclable before disposing of it, 79.3 percent of students reported “always” or “often.”

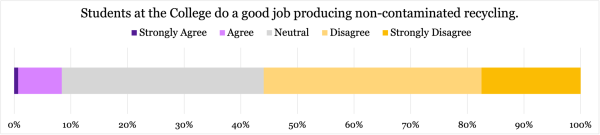

However, only nine percent reported that they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that “students at the College do a good job producing non-contaminated recycling.”

Even among those particularly attuned to waste management landscape at the College, opinions on the quality of student recycling were mixed.

Graham Napack ’26, president of the Williams Environmental Council, said he has not observed students recycling effectively. “I don’t think I’ve been in a single dorm room with a sorted recycling bin,” he said. “Generally, I think most students are exceptionally capable at finding out what is recyclable. I just don’t think anyone puts the time into figuring it out or caring very much.”

Lavinio, one of the Zilkha Center interns, expressed more faith in his peers. “I think students do a good job with recycling on campus,” he said. “The College makes it super easy to recycle since they implemented zero-sort recycling a few years ago and recycling bins are clearly marked throughout campus.”

Though the College’s switch to single-stream in 2021 may make recycling more convenient, the change has not been without its critics.

Moran, though supportive of the single-stream system, described students as often “aspirational” in what they put in recycling bins. By the time Baker and Moran do their weekly pickup, some trash rooms are left in a state of disarray, with contaminants ranging from flexible plastics to hairdryers to urine, Moran said.

Moran and Baker make five to eight trips a day to retrieve bags of recycling from campus buildings and transport them to the Facilities Center on Stetson Road, Moran said. They then dump out the plastic bags that line recycling bins on campus — which are not themselves recyclable — into the compactor.

The Record survey found that 44.6 percent of respondents reported typically enclosing their recycling from their rooms within another layer of plastic bags, which Moran and Baker remove to avoid clogging Casella’s machinery. In a day, they fill at least one 60-gallon trash bag with smaller plastic bags, they said, work students could easily eliminate by dumping out their recycling into the blue bins without a plastic bag, Moran said.

After a quality control check, the recycling is compressed with a giant piston and is ready for pickup, Moran explained. Evans periodically checks in with Casella to learn about changes in the final destinations of the recycling after it is processed in Rutland. When he last spoke to them, he gathered that commingled plastics, tin, aluminum, and glass go to another Casella facility in Auburn, Mass., to be separated, scrap metal goes to an electrical company in Walloomsac, N.Y., and paper recycling goes to a packaging company in Syracuse, N.Y.

Trusting the system

Napack said he believes there’s one key reason for students’ failure to recycle: a lack of trust and belief in the College’s recycling system. Most survey respondents expressed neutrality regarding their confidence that the College ensures that recycling ultimately does get recycled, a sentiment Moran said he understands. After witnessing his own waste collector at his home in Adams, Mass., toss his recyclables in with his trash, Moran began bringing his recyclables to the College. “You get so many answers that you don’t really know who’s telling the truth or what to believe,” he said.

Over the the past few years, the failures of recycling — namely plastic recycling — have entered the national public conversation about recycling, as China stopped taking recyclables from the United States. In addition, reports have emerged that oil companies have run ads in favor of recycling while knowing that the majority of plastics wound up at the bottom of the ocean or in the incinerator.

Many students also reported that they knew very little about what happens to recycling after it is placed in a recycling bin — 37.2 percent said they were “fully unaware.”

Moran, however, has faith in Casella’s work, because he has witnessed it himself. “I’ve gone to the facility, and I’ve seen it firsthand,” he said. “You’ve got folks picking what they can out of it, and then it all just gets recycled. They have bales of plastic and cardboard and paper. It’s pretty impressive, actually.”

In large part due to the efforts of the custodial staff and the recycling team, the College produces recycling for Casella that is less contaminated than the company’s average. “The last time I asked them, our contamination rate was at 3 percent, which is good compared to what [Casella] said on average is 5 percent [among their clients].”

“Williams College does a great job of keeping the recycling clean,” said Joseph Maguire, Casella’s Supervisor of Operations. “We have other colleges that do not do as great of a job.”

Since Evans began working at the Zilkha Center in 2014, he has made it a priority to create consistency and simplicity in the recycling system. “How are we doing what we have in our control to put the right size bins across campus, standardize them to decrease confusion, and put together signage that makes sense?” he asked.

Still, Moran said he sees the potential for better education about the recycling system when students first arrive on campus. “Every four years, you’ve got an entirely different population on campus, so the education has to be consistent,” he said. In the past, however, in-person education about recycling has not been ranked as a priority during First Days, Moran said, though the College does have an online module on Glow on sustainability practices.

Lavino agreed that the College could provide students with a better understanding of what happens to their waste. “I would love to see an improvement from the College on education surrounding waste management of materials once they leave Williams,” he said. “I would say most students understand what it means to recycle, compost, or landfill waste, but most do not know what that means specifically for Williams.”

Evans also said he hopes that further awareness about recycling at the College can help students buy into the system. To that end, Lavinio and other Zilkha interns recently created a video, which was published by the College on YouTube and social media, to further inform students on how to properly compost and recycle.

“We all want to say, ‘I trust the system’ and, ‘It’s worth my time,’” Evans said.

“The people who graduate from here are going to go out and make the world a better place through their education,” Moran said. “But they can also go out and make the world a better place through how they live.”