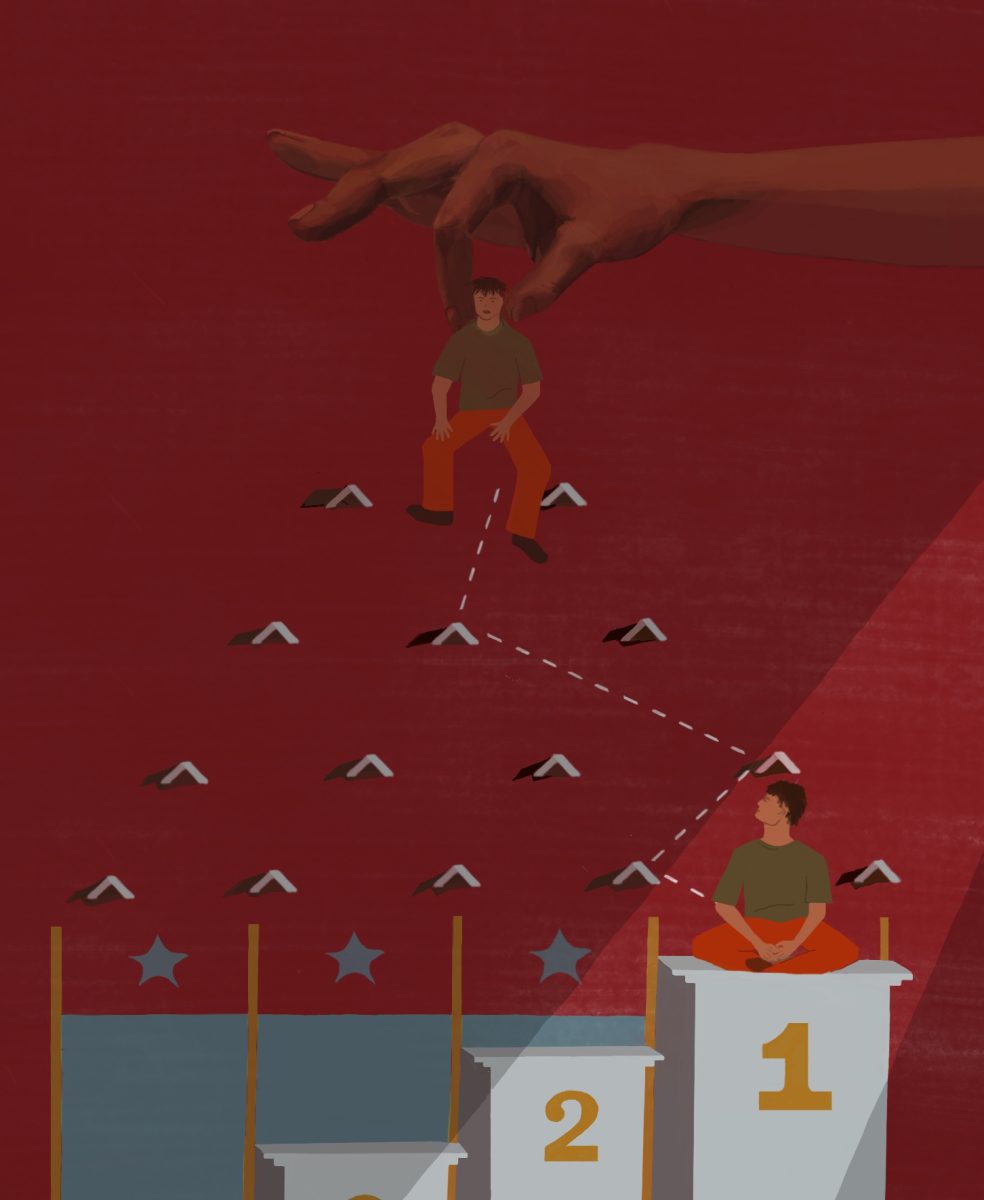

When I started college, I thought I was destined to fail. I had just returned to classes after taking a gap year, before which I attended a public high school that was very different from the College. I thought I wouldn’t belong. I did well academically in high school, but my SAT score was in the bottom quintile of my admitted class at the College. At several points during my first semester, I thought I was failing or might need to take time off to become a better writer and thinker. By the end of my junior year, I was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and selected as a fellow at the College’s Oakley Center, which supports faculty research in the humanities and social sciences. These academic achievements, however, do not tell the true story of my relationship with my education during my time at the College. Imposter syndrome — when people doubt their accomplishments and fear they don’t belong — has shaped my lived experiences as a student, and, as I only came to find out later, it is a lot more common than students think.

During my first year at the College, my imposter syndrome prevented me from enjoying my classes. For my first three semesters, when I did much better than I expected, I constantly thought the next semester would prove that the previous one was a fluke. I spent unreasonable amounts of time on assignments and would often visit the Writing Workshop two or three times for a single essay. I thought that I had to be “perfect” to show that I belonged, and I consumed a significant amount of energy on my self-doubt.

This self-doubt about, my writing in particular, was a significant departure from my childhood. My parents are immigrants from the Caribbean and Japan, and they have spent a lot of time navigating different communities. From their own lived experiences, they knew how to prepare for mine. In particular, my mom and I would pore over books and write short stories about our family histories and “Safire the Penguin,” counting the steps my imaginary penguin friend needed to get to the local elementary school. Writing was a way for me to connect with my lived experiences and heritage, or to dream of other worlds that were accepting of my complex identities as an American from a multiracial, multilingual, and multifaith household.

However, during my first year at the College, I would often need at least 20 hours to write a five-page essay. Now, it takes me five or six hours to write an essay. While I have learned many skills as a Williams student, the most major change in my ability to turn out essays has been understanding that I had been experiencing imposter syndrome and that this was normal.

The first time I heard about imposter syndrome at the College was during my training to become a writing tutor, more than a year into my time here. Some students, staff, and faculty members had discussed issues related to self-doubt, but they rarely named imposter syndrome. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, many students, faculty, and staff led workshops and panels to dismantle the idea of the “perfect” Williams student. However, for the most part, during my first year at the College, I rarely had conversations with other students in which we shared that we were having difficulties balancing many different activities and felt overwhelmed or said the words “imposter syndrome.”

I did not realize that other people felt the same way until later on during my Williams experience, when I had developed community. Through conversations with students, faculty, and staff, I understood that I was not alone. Once I realized that I did not have to prove that I belonged, I began to love learning again.

Reframing imposter syndrome as the common experience it is can help students realize that they don’t need to be perfect to belong to our community. However, addressing imposter syndrome requires a systemic response. Some individuals have made an effort to share their stories, but as a senior and a three-time orientation leader and director, I have witnessed first-years time and again who have actively come to dislike learning because of imposter syndrome.

A systemic response requires difficult conversations about pedagogical goals. For example, students have advocated for the College to implement a mandatory Pass/Fail for first-semester students for years. Peer institutions like Brown, CalTech, MIT, and Swarthmore all have variations of this system, and the College could be well-served by a similar one.

However, I realize that change is difficult, especially at a faculty-governed institution where many faculty members have different grading philosophies. When I served on the Committee on Educational Affairs, we briefly discussed addressing grade inflation at the College, only to table our discussion because almost none of us agreed on the right approach, and several of us challenged whether grade inflation was a problem at all.

Regardless of changes in grading policies, destigmatizing imposter syndrome requires more than brief mentions that it exists. Students, staff, and faculty can create institutionalized spaces to share stories and experiences with imposter syndrome and best practices to address it, including First Days workshops, conversations at the beginning of majority-first-year classes, and training for orientation leaders, Junior Advisors, faculty advisors, and staff on destigmatizing imposter syndrome.

Most students at the College enjoy learning, but our relationships with learning can sour when we think that we don’t belong. Starting college is hard, and imposter syndrome is a shared experience. It’s time that we normalize it.

Hikaru Wakeel Hayakawa ’24 is a history major with an environmental and global studies concentration from Maplewood, N.J.