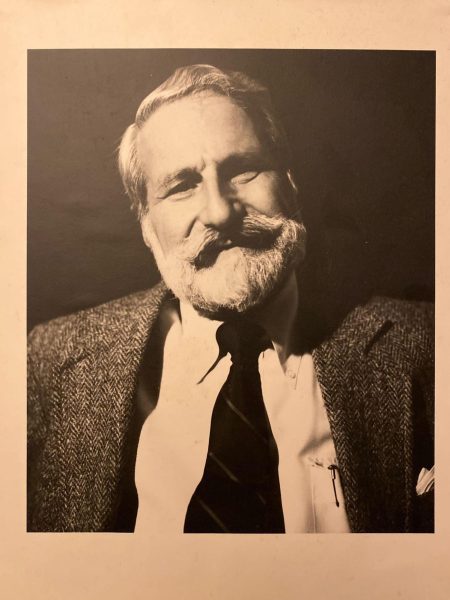

Kurt Tauber, Professor of Political Science Emeritus, died on Jan. 25 at the age of 101. He taught at the College from 1960–93 and is fondly remembered by students, family members, and former colleagues.

In 1984, Ed Stein ’87 — then a first-year — met Tauber through a student organization Stein founded to promote dialogue at the College, an effort Tauber sought to further as the Gaudino scholar at the time. In an interview with the Record, Stein remembered him as a remarkable professor. “He really took his students incredibly seriously as fellow scholars engaged in a question in a way that was quite remarkable,” Stein said. “He had this kind of seriousness, and at the same time, humility to his teaching, that was distinctly engaging.”

“The amazing thing about him as a teacher was that he was so devoted to his students,” Stein continued. “His office door was literally always open, and if you let him, he talked for hours. The amount of feedback he would give on papers or drafts was just unbelievable. He would literally write as many words in comments on your paper as your paper was long.”

Professor of Political Science Mark Reinhardt noted that Tauber worked to democratize the department during his tenure as its chair, opening faculty meetings to students, increasing student input on hiring decisions, and welcoming a variety of perspectives from students and colleagues.

Tauber was born on Oct. 6, 1922, in Vienna, Austria, to Richard and Anny (Kohn) Tauber. He grew up in Vienna with his older sister, Kitty, until Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938 prompted him to emigrate to the United States the next year. He moved in with his uncle Fritz’s family in Melrose, Mass.

Fritz Tauber hoped that Kurt would enroll immediately at Harvard University, but instead, Kurt completed his final year of high school to learn English. At Melrose High School, he met Esther May Moss, who would become his wife of 54 years.

In a self-authored obituary, Tauber quipped about graduating from Harvard in three years with a degree in chemistry. “I persisted in majoring in a subject (chemistry) in which I had soon lost interest, and in any case, was not particularly good,” he wrote. After graduating, he was drafted into the Army Air Corps in 1943 and was honorably discharged in 1946.

After he returned from the army, Tauber pursued a doctorate in government, also at Harvard, which he completed in 1950 with a 570-page dissertation. “The examining committee apparently was so daunted that they awarded me the [Edward M.] Chase Prize [for the best dissertation relating to world peace],” he wrote in his self-authored obituary.

Tauber taught and researched at the University of Buffalo until he was hired at Williams in 1960, where he wrote a two-volume, 1,600-page study of post-World War II German nationalism. “My father, rightly, thought that it would make a good door stop,” Tauber wrote of the book in his self-authored obituary.

“The life of my father was a miraculous bundle of stark contrasts,” Kurt’s daughter Gwen Tauber wrote in an email to the Record. “Often stern, critical, and disciplined, he was also loving, accepting, and flexible.”

An important part of Kurt Tauber’s personal and political identity was his belief in Marxism, which he adopted during the 1970s. “The Vietnam War years were for me as exciting intellectually as they were politically,” his auto-obituary reads. “Radicalized by the events abroad and at home, I began to study and appropriate the complex, sophisticated, and compelling social theory of Karl Marx.”

“He hailed from and cherished his bourgeois Viennese upbringing, while he fully empathized with the masses,” Gwen Tauber wrote. “At Harvard he discovered his love of Aristotle and his concept of ethics as the basis for political science. In his late 40’s, he recognized that the addition of Karl Marx’s insights coincided with his thus far accrued knowledge, experience, and intuition … The discovery was truly enlightening for him.”

“He was very interested in the rights of the working class and racial and ethnic minorities,” Stein remembered of his professor. “The foundation of his Marxist political theory was his contrarian nature. It was something that he held quite deeply and clearly influenced his scholarship.”

“He lived and practiced the contention that human nature requires social engagement to its fullest,” Gwen wrote. “He died as a bundle of love, so deeply thankful for the breadth and depth of his attachment to those he had encountered in life and to their attachment to him.”