Since its founding in 1887, the Record has reported on events of local and international significance. The Record column “Historical Ephvents” explores the paper’s coverage of historical events and their effects on campus. This week, it details how the the Record reported on the Civil Rights Movement of the early 1960s in the lead-up to the 1969 occupation of Hopkins Hall, where 34 students took over the building with 15 demands aimed at diversifying the curriculum and faculty.

Until the 1950s, the Record didn’t often report on world news — with the exception of the two World Wars — and instead focused on sports and fraternity news. For example, the Record did not immediately cover the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled segregation in schools unconstitutional. Nonetheless, the rise of a more activist student body in the early 1960s saw the Record report and comment on national news with increasing frequency.

In 1963, the Record began a nearly three-year period of intensive reporting and involvement in the Civil Rights Movement. For example, the Oct. 2, 1963, issue of the Record covered a talk from William Wyatt, then-lieutenant governor of Kentucky, who praised the court’s decisions to reaffirm anti-segregation and strike down mandatory public school prayer and divinity classes, which he said “have no parallel” in terms of importance.

The article’s writer, R. Lisle Baker ’64, also wrote that the “decisions alone would be enough to mark [Chief Justice Earl Warren] as one of the greatest if not ‘the greatest’ Chief Justice in the history of the Court,” demonstrating a shift to a more politically involved Record.

In that same issue, the Record covered a screening of the film The Cry of Jazz hosted by the College’s Civil Rights Committee. The panel, which included Wesleyan Professor of Religion John Maguire and Professor of Music Irwin Shainman, discussed how jazz was a form of activism.

According to Record reporting, Maguire, a leader of the Civil Rights Movement, argued that for the movement to “retain its role as a conscience for Americans, it cannot be content with achieving the goal of merely a ‘bigger slice of the pie’” for Black Americans. Instead, he continued, it must work for a “total reordering of American society.”

Moreover, the 1960s also saw more students and community members participate in off-campus activism. In November 1963, Steve Block ’65, then-co–chairperson of the Civil Rights Committee, helped the NAACP arrange a donation drive for activism in Williamstown and participated in a rally for civil rights in Pittsfield.

Block told the Record that he hoped to inform people in Berkshire County of the “tragedy of the Southern experience” for Black Americans, as well as the discrimination Black people faced locally. “We expect to aid the concerned people of Berkshire County in their future efforts to lessen the burden of discrimination, most glaring in the field of housing,” he said.

In the March 13, 1964, issue, the Record reported on an exchange program between the College and several historically Black colleges and universities. According to reporting, student applications “far exceeded” available spots.

A year later, in the March 2, 1965, issue, the Record reported that Dave Tobis, the then-chairman of the Williams Civil Rights Committee, detailed plans for the group’s church construction project in Mississippi over spring vacation, which aimed to replace one of the 42 Black churches bombed over the past year. The Record noted, however, that the group would “engage in no direct civil rights activity” while on the trip. There were 12 spots available to students at the College, who were chosen from 36 applicants, the Record reported two weeks later.

That month, students picketed in opposition to Apartheid in South Africa and formed the Student Committee for Restricted Escalated Warfare (SCREW). This new committee was controversial, and the Record described heated confrontations between SCREW and the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) over the most effective methods of protest.

Following the death of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., the April 12, 1968, issue of the Record published a series of reflections from Black students. “The assassination is just a reflection of race relations in America today and of how they have always been,” Cliff Robinson ’70 said.

Marvin Boyd ’70, who praised King’s “sincerity and dedication,” said that he “didn’t go along with the Civil Rights Movement in its concept that demonstrations are going to accomplish something by appealing to the white conscience.”

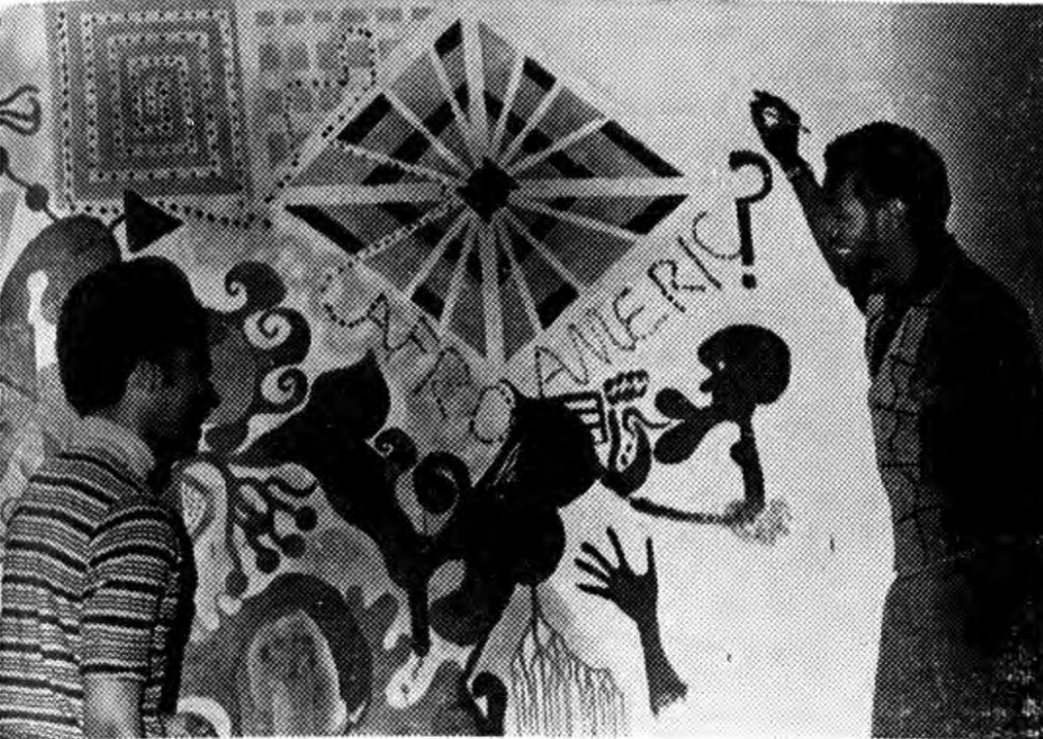

The April 20, 1968, issue of the Record reported on a meeting between several Black students and faculty, where the students called for the adoption of curriculum to bring the “Black man’s culture and heritage into focus and aid in the recruitment of Black students.” Among their proposed changes was a “Martin Luther King Scholarship” and a new faculty position dedicated to the history of Black people’s contributions to the Americas.

In the May 6, 1969, issue, the Record reported on the College admitting 27 Black students — out of a class of 334 — to the Class of 1973, an increase from previous years. This was in part supported by the “A Better Chance” program, which helped recruit students from underprivileged backgrounds, as well as increases to financial aid. Still, however, the number of legacy students admitted was higher than Black students at 33.

By 1968, the College had undergone substantial changes, and if one reads Record issues from 1958 and 1968, one would be reading two fundamentally different publications. Even the very structure of the Record had changed: The sports section was moved off the front pages, and editors placed a greater emphasis on student views and activities.

And on April 4, 1969, 34 students occupied Hopkins Hall, demanding a more diverse faculty and curriculum. Classes were canceled for two days, as protesters and members of the College’s administration communicated by telephone and passing notes through windows.

In the wake of nationwide calls for civil rights, it was clear that the student body was becoming more active in its demand for racial justice — not just in the nation, but also on campus.