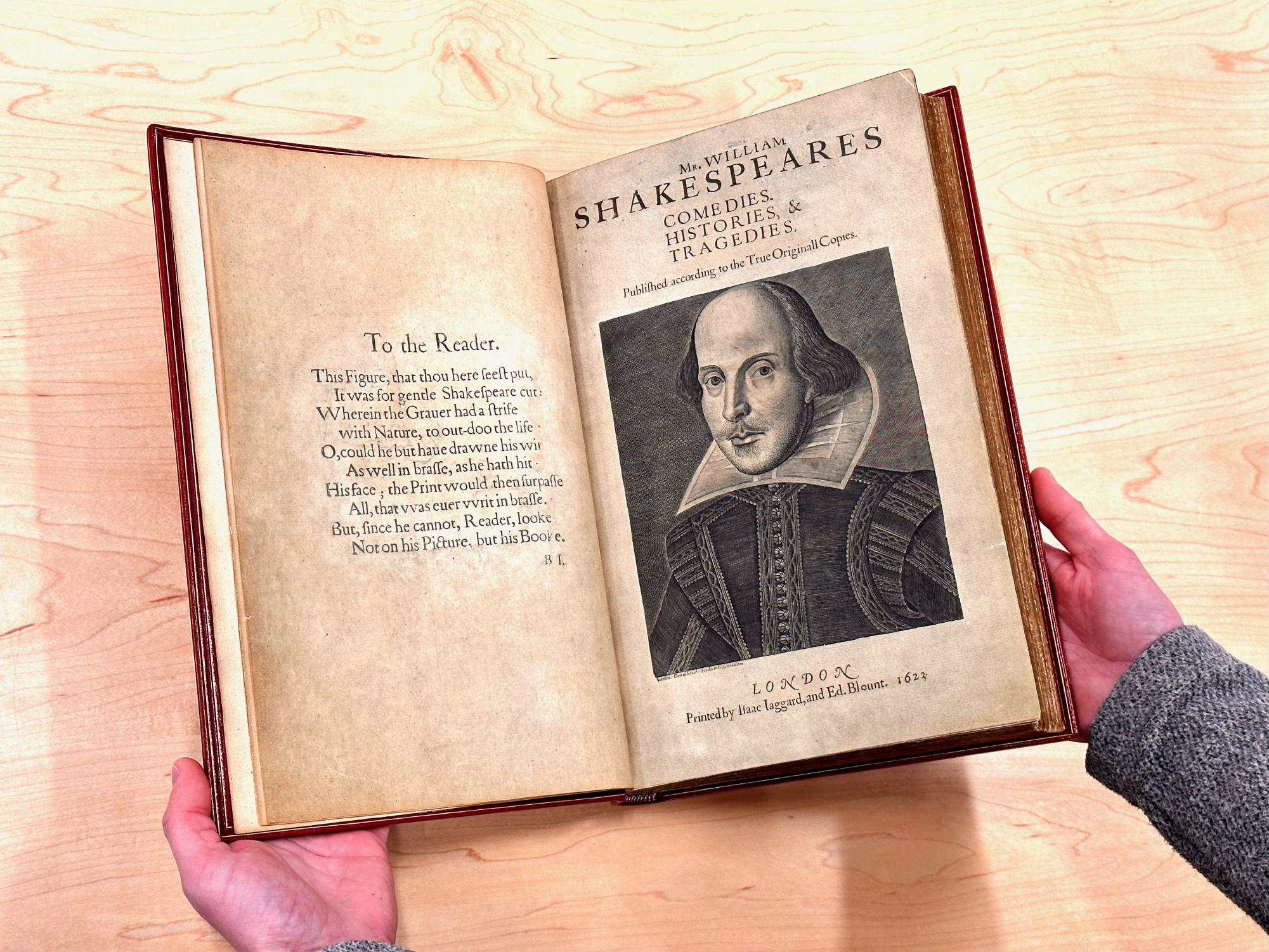

It’s not uncommon for the mere mention of William Shakespeare (or Shakespere, as it’s spelled on the front of Stetson Hall) to be met with an eye roll or an exasperated sigh — Shakespeare-related trauma from high school is very real. However, for unemployed English majors such as myself, 2023 is the time to unabashedly let our Shakespearean freak flags fly. This year marks the 400th anniversary of the publication of the playwright’s First Folio.

For anyone who has yet to be a victim of the English major’s pre-1800 literature course requirement, a folio is essentially just a large book. It is constructed by printing on sheets of paper, then halving them so that each sheet forms four pages.

The First Folio is arguably responsible for Shakespeare’s centuries-long cultural significance — without the First Folio, much of Shakespeare’s work would have been lost to history. Of the 36 plays included in the First Folio, 18 had yet to be published, including The Taming of the Shrew and The Tempest.

Though significant, the First Folio isn’t actually considered a “rare” book. Out of the estimated 750 copies originally printed, 235 are known to have survived — one of which is on display in Chapin Library’s centennial exhibition.

The First Folio comes with a big price tag. In 2020, a copy of the book sold for almost $10 million, making it the most expensive work of literature ever auctioned. But don’t worry — Alfred Chapin, Class of 1869, only paid a modest sum of what would be $680,000 in dollars today for the three folios, one of which is a First Folio, in Special Collections.

So why do people make such a big deal about a book that isn’t even that rare? The answer is quite simple: It’s Shakespeare.

“The single primary driver for [the First Folio’s] expense is because Shakespeare is such a cultural touchstone for the Anglophone world,” Chapin Librarian Anne Peale said. “It’s that sense of primacy and importance that makes it desirable.”

Because of their hefty price tag, most First Folios are preserved behind glass, and few are available to the public — which is why the copy in Special Collections is so special.

Special Collections librarians consider the folios to be extraordinarily instructive. “Whether we’re looking at the history of printing, whether we’re looking at the history of performance, whether we’re thinking about textual histories and textual editing, [the First Folio] really does a lot for us, and that’s a real resource,” Peale said. “It is a book that people tell stories about, and it’s a book that people tend to remember encountering for the first time.”

Professors often ask Special Collections to show their students the First Folio, but its popularity has necessitated a much-needed break to ensure its preservation. In the meantime, the library has retired it to a display case. Special Collections is currently encouraging the use of the less popular — yet much rarer — Third Folio, which offers its own unique contributions to literary history.

However, the First Folio’s importance to the literary world — and its price — does beg the question: Is the experience of being in its presence more interesting than the experience of the text itself? The preoccupation with the physical book itself rather than its content exemplifies its historical and contemporary fetishization.

While the book has come to represent the triumph of canonical European literature, it also exudes a certain sense of Western superiority, which has pervaded much of literary history. People appear more interested in being in the company of the book due to its perceived significance than the knowledge that can be gained from it.

Nonetheless, for Special Collections, the book is representative of the College’s unique teaching philosophy.

“The fact that it was given to the College 100 years ago and has been in almost constant use since then is a real testament to its enduring relevance to the Williams curriculum and student learning,” Peale said. “I think that 100 years of hands-on student learning is something that we can be super proud of, in relation to Shakespeare, but also the other books in our collection.”