While society almost universally agrees that a college degree has become a precondition for economic security, access to the important resource of higher education remains strikingly unequal. Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in a recent series of articles published by The Upshot, the data journalism website produced by The New York Times. These pieces touch on topics including the economic profiles of individual student bodies and, most recently, on parental income and college attendance.

Williams was also featured in each of these pieces. Prominently displayed is the economic profile of the average Eph and the outcome of Weston Hall’s admissions decisions. The picture that these statistics paint is striking.

According to the data published by the Times, a student whose parents are in the top 1 percent of income earners is 10.4 times more likely to attend the College than the average applicant. On the other end of the spectrum, an applicant whose parents are in the bottom 10 percent of income earners are only half as likely to attend as the average student. Even students from families in income percentiles as high as the 85th are significantly less likely to attend the College than their wealthier peers.

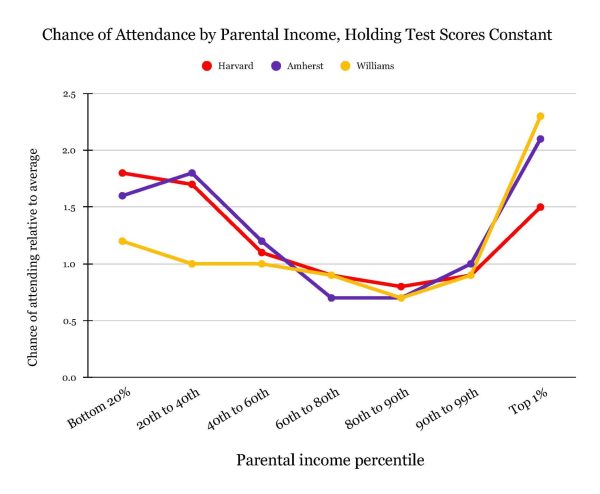

The statistics are slightly less jarring when standardized test scores are controlled for, but they do not paint a different picture altogether. When applicants are compared only to those with the same standardized test scores, students from the top 1 percent of income earners are only 2.3 times as likely to be admitted when compared to the average student, and students from the bottom decile are themselves 1.2 times as likely to gain admission as the average student. Nevertheless, due to the well-documented positive correlation between income and standardized test scores, this means very little. Citing disparate test scores in order to explain disparate admissions is an exercise in willful ignorance.

The specific implications of these statistics are debatable given the complex drivers of generational inequality. One thing, however, is clear: The College’s admissions practices are structured, intentionally or not, in a way that benefits the wealthy.

Though the observation that the College is a place of immense privilege seems self-evident, there is good reason to worry about an admissions system that privileges the successful in such an explicit way. While it may be wrong to discriminate against the poor, accusations of classism alone are not a threat to the College; the implications of those accusations, however — to prospective students, and to employers — should concern the administration.

First, the profile of the College, both as a school that advantages wealthy students and contains a disproportionate amount of them, may give low-income high schoolers pause before applying here. While the College is already a shockingly top-heavy school in terms of class — containing almost as many students from the top 1 percent of families as from the bottom 60 percent, according to The Upshot — the situation could continue to get worse. The College can only accept those students who apply, and if it begins to gain a reputation as a space accessible only to the rich, our economic profile could start to look less like it currently does and more like that of Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., where over 20 percent of students come from the top 1 percent, and only 6 percent of students come from families with incomes in the bottom 60 percent.

If this were to occur, it would have negative social effects, creating an even more insular and economically homogeneous student body. This would not only fly directly in the face of the College’s goal of providing a diverse liberal arts education to all of its students but also leave students unprepared for a post-graduate life outside of the “Purple Bubble.” More importantly, however, it would limit the pool of potential applicants, and thus potentially lower the academic caliber of the student body as a whole. If the College is devoted to one thing, it is educational excellence; it prides itself on being academically rigorous, and its identity as such is one of the primary draws for students and employers alike. If the College were to develop an identity as a school for wealthy students only, rather than as a true meritocracy that seeks the most qualified students from across the country, both the management consulting firms and ambitious high school seniors who currently flock to this place might begin to look askance at the Purple Valley and set their sites on more economically diverse institutions elsewhere.

In any potential effort to create a more egalitarian admissions process, the College would be understandably constrained by economic considerations and tradition. However, constraints do not preclude the possibility of action. Peer institutions like Harvard and Amherst, for example, have notably less unequal parental income statistics, and they continue to be two of the most well-regarded colleges in the country.

Moving forward, the College should do everything in its power to expand the pool of applicants and attendants and bring together a more economically diverse student body. This should involve building relationships with high schoolers, high school guidance counselors, and administrators in places where Williams College is an unfamiliar name. Currently, the College is well-known in choice suburbs and wealthy urban enclaves in the Northeast, and much less well-known across the rest of the country (and, indeed, the world). This is likely a driving factor behind the College’s current demographic inequality. If the College can familiarize itself with non-traditional communities and make the people in them familiar with its name, it can draw as diverse an applicant pool as possible and produce as intellectually rigorous of a student body as can be. Until then, the College can only strive to be a place of true academic excellence.

Nelson Del Tufo ’25 is a political science major from Big Indian, N.Y.