STEM, economics departments stretch to meet rising course enrollment

Each day, more than a thousand students descend on Science Quad, filling classrooms and crowding into office hours. Computer science professors teach five sections of their introductory courses, statistics professors lecture to audiences of 80, and more students pre-register than departments are able to comfortably serve. “We’re victims of our own success,” Chair of the Mathematics and Statistics Department Richard De Veaux said.

De Veaux joined the College in 1994 as its first statistics professor. When he taught “Statistical Design of Experiments” for the first time in 1995, eight students took the course. This past fall, when he offered the course again, 40 students enrolled.

“It was terribly, terribly crowded,” he said. “We did as much as we could.”

It isn’t just Statistical Design: De Veaux said he expects courses across the mathematics and statistics department to exceed their enrollment caps in the next academic year. When the College established its statistics program in 2002, enrollments totaled 212. This year, the number of enrollments stands at 563. By the time they graduate, roughly 65 percent of students will have taken at least one statistics course. “We’re inundated,” De Veaux said. “And we need help.”

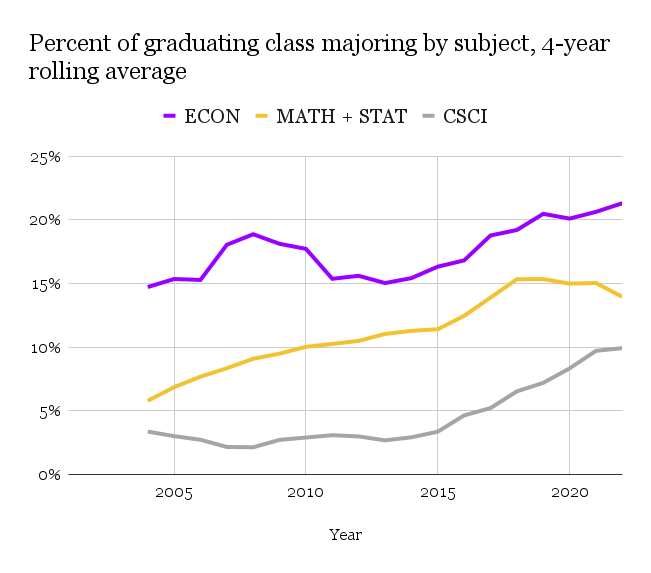

While some humanities departments at the College have seen declines in course enrollment and major declarations, departments such as computer science and economics have experienced trends heading in the opposite direction. In 2007, Division 3 overtook Division 1 in student course enrollment, and since then, the gap between them has only widened.

Much of the growth in Division 3 has been driven by the College’s statistics and computer science programs, newer departments which have rapidly become two of the College’s most popular offerings. Other STEM fields, including biology and chemistry, have also experienced growth. And economics, which has long been a popular discipline at the College, has recently seen a record-breaking number of majors.

Though growing popularity in these departments has delighted professors, it has posed its own challenges. Now, these departments must balance surging demand for their classes with limited resources and a desire to preserve the small, intimate atmosphere that defines a liberal arts education.

In the second of a two-part series, the Record spoke to professors in the mathematics and statistics, economics, and computer science departments about the effects of rising interest in their disciplines. Read part one here.

“The new liberal arts”

Professor and Chair of Economics Jon Bakija, who arrived at the College in 1999, now helms its most popular department. This year, economics boasts 1,694 enrollments — more than every foreign language class combined. In June, 135 seniors will earn degrees in economics. “This year is a record for us in terms of total number of majors, but there’s been a pretty straight, steady upward trend,” Bakija said.

“There are different theories for why this is happening,” he continued. One theory, according to Bakija, is that students care more than ever about their career prospects. “The career center has this mantra [that] ‘major does not equal career’ — but major is correlated with career, especially in certain types of careers,” he said.

As the College has grown more diverse, De Veaux said, students’ need for financial stability has become more pressing. “Who was the typical student in the 50s or 60s who came to Williams?” he asked. “A privileged white man, whose choice of major may have been less important as a practical matter since they knew they would be financially secure in any case.”

The College has changed in other ways since the 1950s. Today, increasing numbers of graduates move from the Purple Valley to Silicon Valley, where they work as programmers and data scientists.

In 2002, when Chair of Computer Science Stephen Freund arrived at the College, the invention of the iPhone was still five years away. Over the years, Freund’s academic discipline has continued to evolve rapidly. “We have to reinvent what we do and reimagine what we’re teaching students on a very regular basis,” Freund said. “This pace of change makes it an exciting time to be a computer scientist.”

Fifteen students majored in computer science in 2002. The number of majors now hovers at 50. Over the same period, annual enrollment has climbed from roughly 300 to 720.

“We’re riding a wave of data,” De Veaux said. “Everybody should know how to ask the questions about this wall of data that we’re inundated with every day.”

“It’s the new liberal arts,” he added.

“Near crisis conditions”

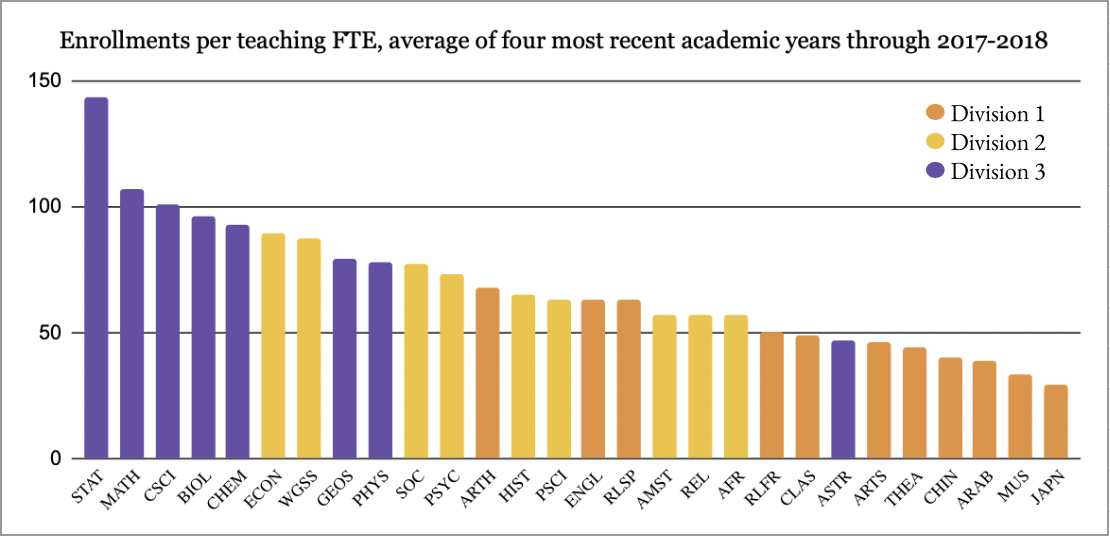

The explosion in demand for courses in the areas of computing, data analysis, and biomedical education has driven some departments “to near crisis conditions,” the Curricular Planning Committee (CPC) reported in 2018.

This problem has rocked other institutions of higher education across the nation. But unlike many universities, where professors pass off some of the burden of educating students to teaching assistants, the College’s small size and the nature of its mission require professors teach every class and grade 85 percent of coursework.

“It’s a challenge for us… because we have so many students per faculty member,” Bakija said. “We’re managing, but it is a little precarious.”

When departments see preregistration numbers exceeding enrollment caps, they are forced to make a choice: Professors can turn students away, or they can expand the size of their classes beyond what is typical at the College.

“Oftentimes… they just cap it and kick the students out,” Bakija said. “Then [students] eventually have to scramble to get some other class.” But if professors allow classes to run large instead, the classroom experience can suffer. “Trying to run a research discussion seminar … doesn’t work very well when you’ve got 29 people in a class that was supposed to be capped at 19,” Bakija said.

As with economics, the number of students pre-registering for computer science classes has surpassed what professors see as healthy enrollments. In response, the computer science department has altered its program by removing all tutorials from its offerings, increasing the enrollment cap on its courses, and shortening labs.

“We’ve had to make some difficult choices over the years in how we administer our program,” Freund said. “But we have intentionally made choices that enable us to scale more without substantially compromising on quality.”

Many professors emphasized that enrollment pressures can most easily be relieved by hiring more faculty for overenrolled programs. However, at an institution where resources are finite and the number of faculty is held roughly constant, the decision to hire more professors isn’t made overnight.

Adding just one tenure-track faculty line costs the college several million dollars in present value, the CPC reported in 2018. “We must move very cautiously when considering any kind of sustained expansion to the number of faculty at the school,” it wrote in its report.

The number of professors in the computer science department has recently increased from eight to 13, which has helped mitigate the worst of the enrollment pressures. “We’ve finally gotten some breathing room where we can actually take a step back and think carefully about how we want to move forward and envision our curriculum,” Freund said. “It’s hard to know whether 13 is the number that we ultimately land at … It could be higher, [or] it could be lower. That’s something that will be a continued, long-term discussion with the administration.”

The mathematics and statistics department regularly requests new faculty members from the College, according to De Veaux. “We’re not trying to be greedy,” he said. “Unfortunately, it’s a zero-sum game. We’re all colleagues. It’s hard.” In 2018, the enrollment-to-faculty ratio for statistics was the highest of any program at the College by a wide margin.

Because hiring a new professor represents a significant commitment of resources, Bakija does not believe the College will allow his department to grow in the near future — but he believes it can make do with its current size.

Uncertain futures and educational ideals

Deciding which academic programs to prioritize, regardless of their enrollment, is an extraordinarily difficult task. Every professor interviewed by the Record emphasized that they were glad not to be directly involved with the decision-making process.

The College, then, faces difficult lines of inquiry moving forward. “Do we get driven by some sense of the faculty about what students should want to take, or do we get driven by the students and what they want to take?” De Veaux said. “There’s not a clear answer.”

These questions were once the domain of the Curricular Planning Committee, which was charged with considering questions about the College’s academic future and long-term curricular changes, though it had no authority over hiring and funding decisions. The CPC disbanded in 2020 and has not been replaced, though aspects of its work are now represented in the College’s Strategic Plan and the work of other committees.

The Record spoke with Professor and Chair of Religion Jeffrey Israel, who was a member of the CPC until it disbanded. “It’s hard to look at the pressures that the faculty in [programs] like computer science are under and think that’s a fair situation,” he said. “They have an enormous amount to do just to get through the day-to-day demands of managing student interest.”

But Israel said that, even while it existed, the CPC struggled to come to a consensus about what a fair system might look like. Still, he stressed the College’s obligation to establish and articulate its own educational priorities.

“Without some designated institutional body with its eyes fixed on educational ideals,” he continued, “the College is in danger of devolving into a merely reactionary stance, desperately trying to meet consumer demands under the cover of fashionable higher education platitudes.”

“We still lack the most fundamental resource needed to deliberate about [faculty] requests from a long-term curricular perspective: a decisive educational vision,” Israel concluded.

Julia Goldberg ’25 is an English major from New York, N.Y. She is a senior writer. She served as the editor-in-chief in fall 2024, and before that, as...

David Wignall is an economics and history double major San Francisco, Calif. He previously served as a senior columnist, an executive editor for investigations,...