College reckons with declining interest in the humanities

In the fall of 1993, an eighth of the student body enrolled in ARTH 101-102, the College’s introductory course in Western art history. At the time, art history was one of the most popular programs on campus — by the time they graduated, roughly 60 percent of students had taken at least one class in the field.

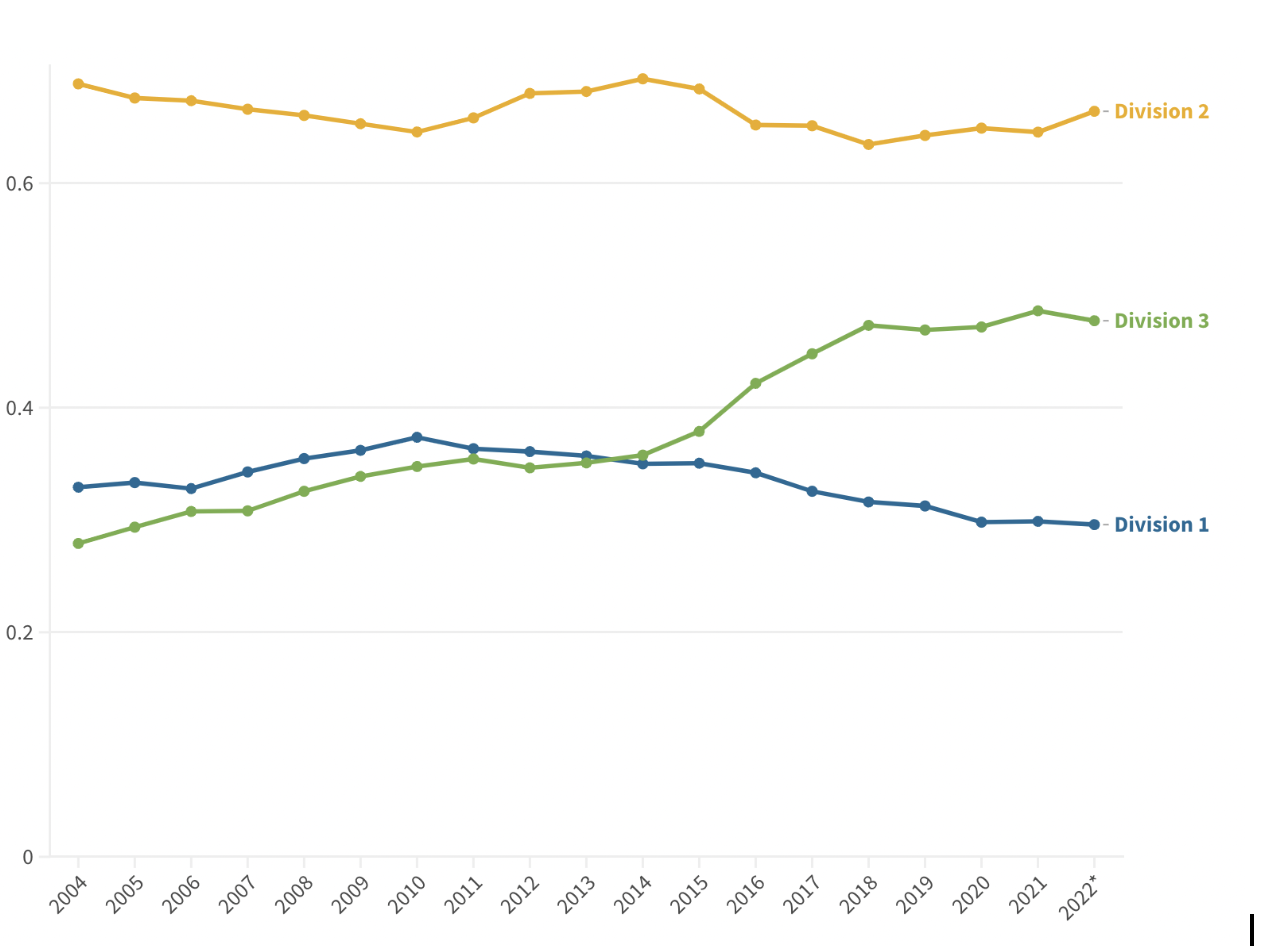

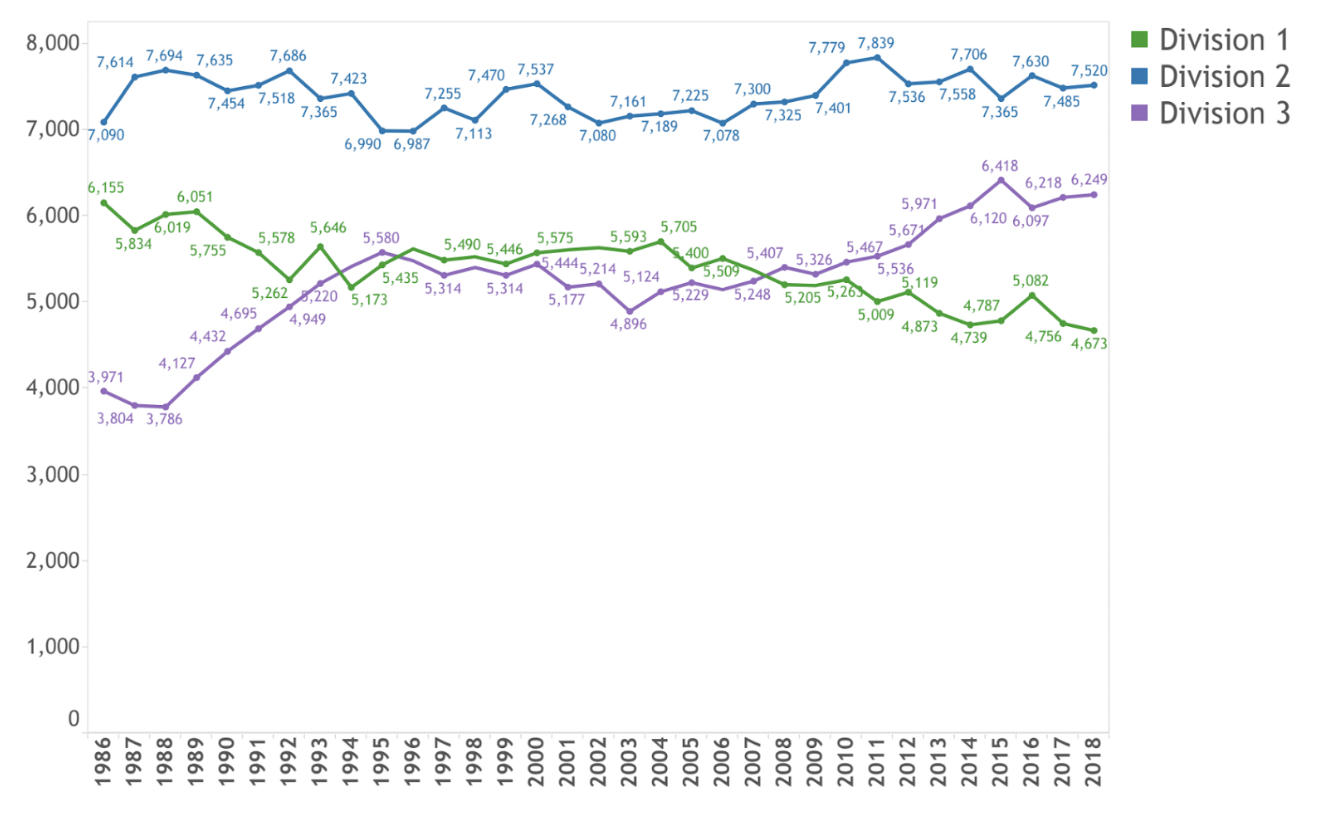

Three decades later, ARTH 101 and 102 remain, but the College’s educational landscape has changed. The number of Division 3 (STEM) majors has more than doubled since 1993, while the number of Division 1 (languages and arts) majors has declined, and the number of Division 2 (social sciences) majors has remained roughly steady. Course enrollments have evolved similarly. Today, compared to three decades ago, students take at least 20 percent more Division 3 courses, 20 percent fewer Division 1 courses, and approximately the same number of Division 2 courses.

The surge of interest in STEM is not unique to Williams. Across the country, institutions of higher education have struggled to adjust to sky-high demand for STEM courses and weakening interest in the humanities. Williams — with its $3.5 billion endowment and traditional focus on the liberal arts — has been relatively insulated. But the College is not immune, prompting academic departments on both sides of Route 2 to consider their circumstances and what the future might hold.

In the first of a two-part series, the Record spoke to chairs and professors from departments that have seen shrinking enrollment. In part two, the Record will investigate the impact of surging enrollment on the mathematics and statistics, economics, and computer science departments at the College. Read part two here.

Professor of Art History Michael J. Lewis, who currently teaches ARTH 102, joined the College’s art department in 1993. “I got on board a ship that was going full speed toward a destination with a great crew, good morale,” he said. “And then, bit by bit, some people jumped overboard, and some people were thrown overboard, and we gradually changed course.”

While the total number of studio art and art history majors has declined since 2001, it is the decline in overall course enrollment that most preoccupies Lewis. Art history courses, which were once taken by 65 percent of the student body by the time they graduated, now reach less than 40 percent. “The audience we’ve lost is those biology, economics, and history majors who believe they need some basic cultural literacy before they become doctors, bankers and lawyers,” Lewis said. “We’ve lost that audience.”

1. Evolving priorities: Students increasingly seek Division 3

As snow blanketed campus and sent students seeking the shelter of their dorms, Chair of the English Department Bernie Rhie ran his finger across the cells of a spreadsheet and reflected on his department’s enrollment. “There has been a general decline,” he said. In 2005, when Rhie began teaching at the College, the English department had 1,494 course enrollments. This year, the tally stands at 1,122.

“I am cautiously okay with where we’re at,” Rhie said. “But definitely worried that, given the overall shifts in student interests, we could become too small to do what we do well.”

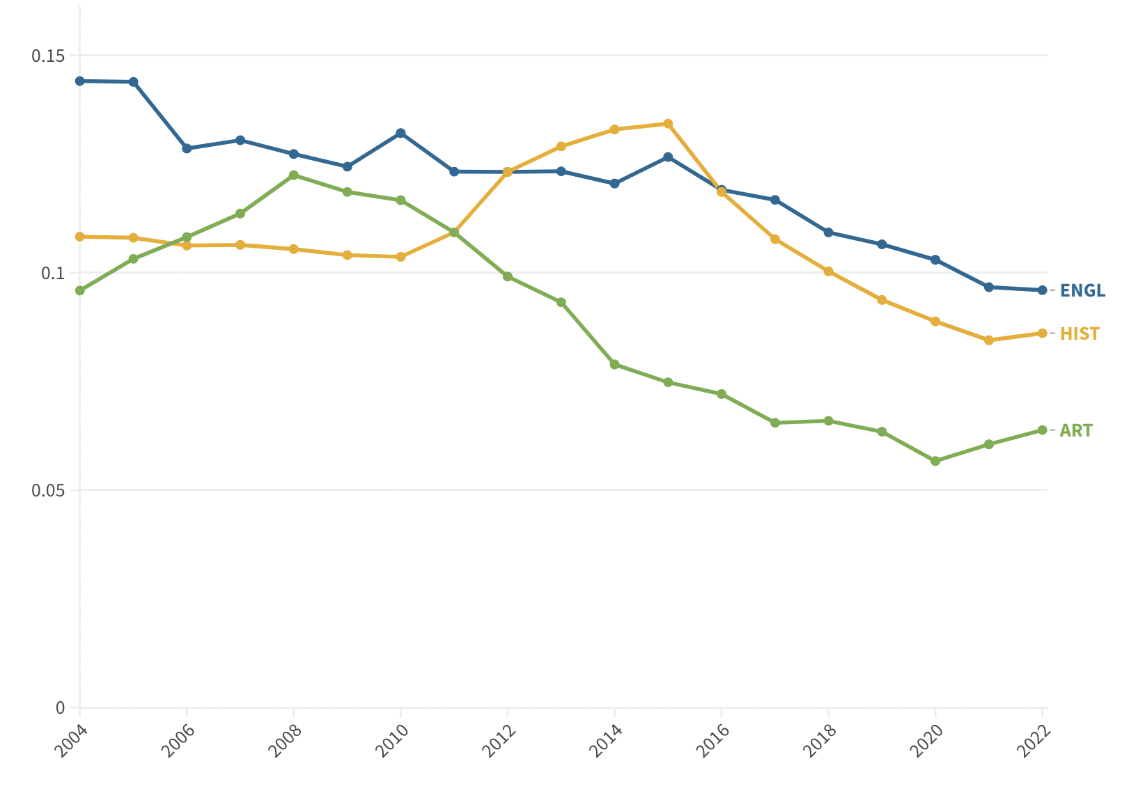

The number of students choosing to major in English — as with all subjects — fluctuates significantly depending on the year, but the trend is clear: Over the course of the last two decades, the four-year average number of English majors in a given graduating class has decreased from the mid-70s to the mid-50s.

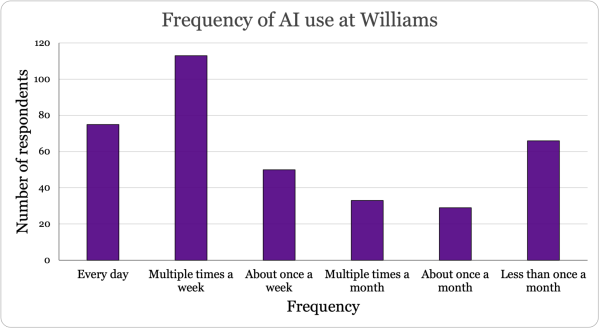

Percent of Graduating Students Who Majored in English, Art, and History, by Graduating Class Year (four-year rolling average)

Overall, even accounting for psychology’s move from Division 2 to Division 3, the number of Division 3 majors at the College has skyrocketed. While much of that growth has been driven by an increase in the number of students double-majoring, Rhie also attributed part of the shift in interest to two other factors: increased financial insecurity among students in the wake of the Great Recession and displacement caused by the creation of departments and programs in adjacent fields.

Percent of Students with Majors in Each Division, by Graduating Class Year (four-year rolling averages)

“I think the 2008 financial crisis very understandably made both students and their families anxious about career outcomes,” Rhie said. “That’s probably the moment where we can start to see a real noticeable turn toward STEM.”

The changes can be seen even before students declare their majors at the end of their sophomore year: Applicants to Williams have gravitated toward the sciences as well. “Since 2009, the percentage of students expressing interest in and choosing to major in Division 1 has declined significantly,” the now-defunct Curricular Planning Committee (CPC) reported in 2018. “Students clearly have a sense of where job opportunities are abundant and high-paying and are drawn to those fields.”

But students’ concerns regarding job opportunities may not align perfectly with reality. Williams alums often pursue careers in fields unrelated to their major, and many traditionally high-paying fields, like law and consulting, hire students from a diversity of undergraduate majors. Though many national studies indicate that STEM and business-oriented graduates, on average, earn higher salaries, professors stressed that lucrative pathways remain open to humanities students as well.

Total Enrollments by Division and Academic Year, 1986-2018

“I think it’s not necessarily true that majoring in English would lead to worse outcomes than majoring in things like computer science or economics,” Rhie said. “But I can totally understand why people might feel that way.”

Professor of History Roger Kittleson has taught at the College for 25 years. In that time, Kittleson said, he has witnessed student anxieties rise in times of increased economic insecurity. “Financial crises really get people looking for solid ground,” he said.

While high-paying jobs remain within reach for history majors, according to Kittleson, certain career paths, such as those in academia, have become less reliable. “The number of tenure-track jobs in history is down,” Kittleson said. “Only about 30 percent of faculty in this country in history are on the tenure track.” In 2019, across all disciplines, 37 percent of newly hired professors in the United States were on tenure track, according to the American Association of University Professors. Furthermore, colleges and universities across the country have recently implemented policies to undermine tenure, including replacing many tenured positions with adjunct and visiting roles, and instituting post-tenure review.

“If there ever was a direct career path [for history majors], it was toward tenure-track academia,” Kittleson said. “That’s not much of a path anymore, which makes those of us who are on it feel incredibly lucky and really anxious, looking forward and seeing our profession eroding.”

As the path toward tenure grows more narrow and uncertain, especially in fields associated with the humanities, career anxieties among students pursuing jobs in academia may have grown. However, Kittleson noted that Williams students rarely choose to become professors. “Very few of our students have ever gone onto that path, even when it was a broader or more welcoming path,” he said.

Though history enrollments and majors have declined since 2001, Kittleson said that his department still serves a healthy number of students, especially compared to some humanities programs at other schools. “At other places, there have been plenty of cases where entire programs and departments have been eliminated,” he said. “Williams is not about that.”

Students have not just moved toward STEM. As the College has established new departments and interdisciplinary programs, there has also been significant movement within divisions.

“Over the last ten years, more and more departments and programs have recognized and embraced various forms of connection within and beyond their own units,” the CPC wrote in 2017, remarking on a trend that has since continued. Last semester alone, the College established an Africana studies major and an Asian American studies concentration, and it also launched the Global Scholars Initiative. In 1996, the College offered 29 majors and seven concentrations. Now, it offers 36 majors and 14 concentrations.

As offerings have expanded, a portion of students and faculty have moved away from older departments and programs. Students hoping to study literature, for example, can now choose classes offered by departments including Africana studies and American studies, according to Rhie. “People who want to study literature don’t necessarily need to turn to the English department to do that,” he said.

“The important thing is not whether or not we have the same number of majors we did 10 or 20 years ago,” Rhie continued. “But rather that students have been exposed to the important kind of skills they get by studying literature.”

2. Funding departments: “Something close to zero growth”

As students veer toward STEM courses, the College must toe a difficult line: while growing departments require more faculty, departments with declining enrollments still need professors to provide the high-quality education on which the College prides itself.

When a professor retires or departs from the College, there is no guarantee that the College will replace them with another professor entering the same department. As such, academic disciplines can grow and shrink as professors depart.

While the College has increased the number of faculty in each of the three divisions over the last two decades, it has more recently adopted a more conservative policy with regard to its faculty hiring practices. “In order to maintain a sustainable budgetary situation,” the CPC wrote in 2018, “the College needs to be very cautious about adding new faculty lines and is currently pursuing a policy of something close to zero growth in the total number of faculty.”

Some humanities professors expressed concerns that, if enrollment shifts continue or become more dramatic while the zero-growth policy remains in place, resources may be diverted from their departments. Nevertheless, they said they had faith that the College would make wise decisions.

“I think that some shrinkage is okay,” Rhie said. “English doesn’t have to be as big a department as we have been in the past. But I think there’s a limit beyond which we do not want to shrink, or else we’re not going to be able to do the work we’re here to do for students.”

The College’s allocation of resources between departments is managed, in large part, by the Committee on Appointments and Promotions (CAP), which oversees faculty hiring. Every year, departments across campus send requests to the CAP for more resources. The CAP then chooses which proposals to accept or reject. In a given year, the CAP receives 20 to 30 requests, according to CAP representative Protik Majumder.

“It’s a competition, it’s a marketplace,” Professor of Studio Art Michael Glier said. “You go and then you make your pitch, and they compare it to other pitches, and you get something or you don’t. And that’s fine, since the goal we all share is to make a dynamic curriculum for the College, not just a department.”

“There’s a lot more [departments] that are competing for faculty resources,” Rhie said. “In that environment, for sure, English has been shrinking. And I think that’s probably been true for the humanities in general.”

Glier said that the studio art program would benefit from hiring another professor with expertise in drawing and painting or photography — but that the CAP may be more likely to allow another department to hire a professor in an emerging field that is not already represented in the course catalog. “That’s going to be a sexier request than having a second painter,” he said.

As of now, Glier said, studio art has enough faculty members to run a “very comprehensive program” in which students can experiment with a variety of media unavailable at other colleges. “That being said, no, we cannot now accommodate the number of students who want to participate,” he said.

Two professors have retired from the history department in the past two years, and two more will retire next year. “We do not expect to replace all of those people — certainly not with people in the same fields,” Kittleson said. “It would be nice to be in a growth situation … because we are also changing.” In recent years, the history department has worked to diversify its offerings to include courses that center on non-Western regions — an effort Kittleson said will continue in the future.

Still, Kittleson said the College boasts a healthy history department, especially when compared to other institutions. “We are blessed with a lot of resources at Williams,” he said. “We have not suffered the kind of loss [of resources] that would affect our curriculum and what we can offer to our majors.”

Rhie noted that the English department currently teaches as many students as it can, given its size. “We would probably teach more if we had more faculty,” he said.

“I worry a little bit about what would happen if we don’t get the support to continue doing what we’re doing,” Rhie continued. “That will require investment by the College and replacing faculty that we’ve lost — maybe not up to the levels that we used to have, but definitely at least maintaining and maybe growing a bit from where we are at right now.”

3. Outlook

In their interviews with the Record, professors advocated for the value of the humanities in an academic environment that continues to evolve.

“I have some faith in the College, that they understand the importance of the humanities for a well-rounded liberal arts education,” Rhie said. “I think that what we do matters, even for students who want to focus in majors in Division 3 and focus on STEM careers. I think the kinds of thinking that we teach and nurture in our classes matters for people in general. And it’s the kind of thinking that this world needs a lot more of.”

“It is impossible to understand the world today without a good, critical understanding of what has made it the way it is,” Kittleson said. “Without an empathetic understanding of what people living in different contexts, periods, and societies have thought of the world … I just don’t think you’re going to understand the world.”

In the coming days, students will peruse the College’s latest course catalog, talking over its offerings with friends and advisors. They will have the opportunity to take hundreds of courses in a diversity of subjects across the humanities. Students at other schools, however, may not have access to the same variety. “I think a lot of what we think of as a crucial part of the liberal arts are in trouble right now in the country as a whole, just not as much at places like Williams,” Kittleson said. “And I think that gap is going to widen. I say that with anxiety and sadness.”

Read part two.

David Wignall is an economics and history double major San Francisco, Calif. He previously served as a senior columnist, an executive editor for investigations,...

Julia Goldberg ’25 is an English major from New York, N.Y. She is a senior writer. She served as the editor-in-chief in fall 2024, and before that, as...