Writing the history of the College: My experience at the Special Collections Transcribe-a-Thon

March 8, 2023

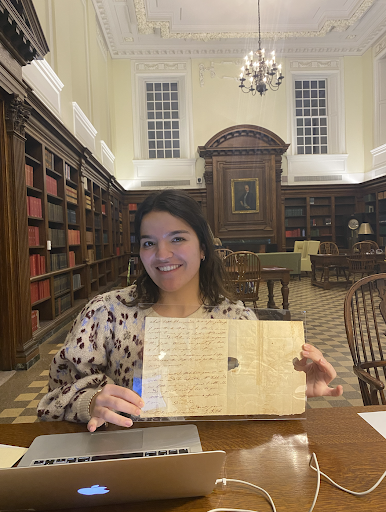

“When I walked in here, I thought that I was a part of something really important,” Anamaria Pla-Avalo, a Spanish language teaching assistant from San Juan, Puerto Rico, told me at last Wednesday’s Transcribe-a-Thon event.

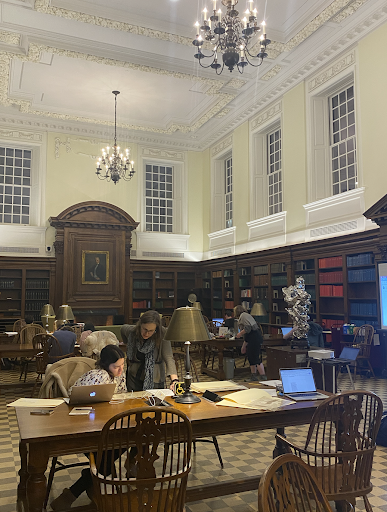

We sat on opposite sides of a table in the Stetson Reading Room in Sawyer Library — my back to the fire, documents written in loopy, slanted cursive on the table before me. Pla-Avalo was reading a letter written by Edward Dorr Griffin, the president of the College from 1821 to 1836; I, a letter by Zephaniah Swift Moore, president from 1815 to 1821, who would infamously defect from Williams to found Amherst College.

March 1 marked the College’s second in-person Transcribe-a-Thon, which is hosted by Special Collections to give students the unique opportunity to transcribe original primary source documents from the history of the College.

“We wanted to be able to give people who didn’t necessarily encounter Special Collections in a classroom setting the chance to interact with the work,” said Chapin Librarian Anne Peale, one of the event’s coordinators.

Although the event occured virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic — utilizing breakout rooms to assign multiple students to the same documents — in-person connection was sorely missed. “You don’t end up having these types of conversations with people,” Peale said.

I noticed a certain spontaneity and warmth in the event that I felt would have been hard to replicate in a virtual setting. Students wandering into the Reading Room, textbooks in tow, were invited to peruse the documents by Peale and her colleague, Head of Special Collections Lisa Conathan. I too found a welcome distraction from my impending coursework while at the event, disregarding my carefully planned evening schedule and staying longer than I’d intended.

While the first Transcribe-a-Thon in 2020 focused on Indigenous history at the College, this year’s event centered around letters written by early College Presidents.

“A lot of [the letters] are fairly routine,” Conathan said. “We find that that is a really interesting way to get a glimpse of everyday life of the business of the College in the 18th century.”

This focus was chosen not only because of the utility of the seemingly mundane as a historical tool, but also because of the difficulty these early writings pose to modern readers.

“The earlier the letter, the harder it tends to be to skim for a modern reader, and the harder it is to access that knowledge,” Peale said, citing hard-to-read handwriting, outdated language, and confusing abbreviations as common obstacles. In fact, it took Pla-Avalo over half an hour to transcribe one paragraph of her letter due to an especially illegible script.

The letter I was transcribing, in which Moore announced his acceptance of a position at Amherst, was not quite as routine. But this event allowed me to hold in my own hands the beginning of an important piece of campus culture: the Williams-Amherst rivalry.

Like any dutiful Williams student, I have a passionate aversion to Amherst. I’d seen Moore’s name on Homecoming banners, but prior to the Transcribe-a-Thon, my knowledge ended there. There was something quite intimate in learning about an important College figure through his words and script. I came to recognize the ways that he looped his uppercase I’s and the noticeably long dash in his t’s.

Documents were chosen, in part, to reflect this humanity that I had felt in Moore’s own voice, Peale said.

“I think there’s also — at Williams — a real desire to connect with our institutional history and to account for it in both positive and negative ways,” Peale said.

The work of the students and faculty members who attended the Transcribe-a-Thon will make these letters and documents accessible to the larger community. “We have the ability to put digital photographs and also text transcriptions directly into the library catalog,” Conathan said. “It makes it much easier for students to discover them.”

But, looking past the digitized results of our work, Pla-Avalo and I both found immense value in the process itself. For me, helping transcribe Moore’s history felt like an intertwining of our stories across two and a half centuries — the weight of which was humbling and thrilling.

For Pla-Avalo, the Transcribe-a-Thon was a way to better understand the College during her one-year program. “I feel connected to the College, even though I’m not a student here,” she said.