New WCMA exhibition ‘Across Shared Waters’ explores Tibetan art, identity

March 8, 2023

༡

Two massive Buddhas had been staring down at me for weeks, and it was starting to feel personal. The one on the left was faceless, composed of tulips, leaves, and branches that twisted and thickened at points to outline the contours of a seated figure. To the right was a more classic depiction, the likes of which I’d seen inside monasteries and on the walls of relatives’ homes. It was a scanned and cropped image of an 18th-century thangka: a Tibetan Buddhist genre of elaborate paintings done on cloth. This one’s face and pose were meant to exude serenity, but after glancing at it enough times on the way to and from my dorm, I felt that its expression had begun to look more puzzled than anything else.

This may have been because of the two figures’ unfamiliar surroundings. They had been emblazoned one story up on the brick facade of the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA), overlooking a plaza and some dorms, in order to promote an exhibition displaying their normal-sized selves.

“Across Shared Waters: Contemporary Artists in Dialogue with Tibetan Art from the Jack Shear Collection” soft-opened at WCMA on Feb. 17. The following weekend, I attended a media tour and the opening celebration for the exhibition. In between taking pictures to send to my family members — who were excited and surprised about how so much Tibetan art had ended up in Williamstown — I spoke with the show’s curator, two featured artists, and the art collector who had supplied the thangkas that formed the impetus for the exhibit. I hoped to explore a few questions:

What sort of dialogue were the artists engaging in?

What stories did the contemporary pieces by artists of Tibetan descent tell about the present-day identity and culture of a diaspora that has existed since the 1950s, when China invaded Tibet and began an occupation that continues to this day?

And there was another question, mentioned implicitly in several paragraphs printed on the wall near the exhibit’s entrance. It is unclear how the centuries-old thangkas made it out of Tibet and across an ocean to end up in Shear’s private collection in the United States. What is one supposed to do about that?

༢

One of the first things a viewer might notice about “Across Shared Waters” is that all of the English text in the exhibit is accompanied by Tibetan, thanks to translator Rongwo Lugyal.

“Even if only one person of Tibetan origin or Tibetan heritage has an encounter with it, I want them to be able to recognize from their cultural perspective how it’s described, rather than me as a cultural outsider saying you have to experience this Tibetan piece solely through the English language,” Guest Curator Ariana Maki said.

Maki is the associate director of the University of Virginia’s Tibet Center and Bhutan Initiative. As we toured the exhibition, she explained that in addition to ensuring a meaningful experience for Tibetan visitors, she also sought to introduce visitors to Himalayan and Tibetan art and history who may never have encountered it in depth before.

Once inside the exhibition hall, she outlined how the exhibition was organized. Thangkas and other traditional art are interspersed with contemporary work to form the titular dialogue. The two seated Buddhas that advertise the exhibit on the building’s exterior greet the viewer upon entering.

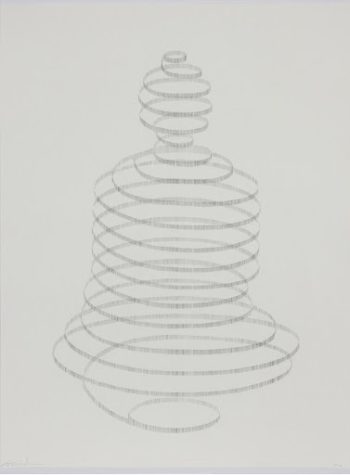

Among the more striking pieces is Tibetan-American contemporary artist Palden Weinreb’s minimalist rendition of a seated Buddha, “Untitled,” which hangs on a wall just feet away from the colorful splendor of an 18th-century thangka.

Later in the exhibition, Marie-Dolma Chophel’s “Inner Dialogue,” an abstract scatter of layers of paint resembling a nebula flecked with color, is positioned next to a traditional mandala. Maki explained that she had put the pieces side by side in part due to the similarities between the meditative practices encouraged by both of them.

༣

Chophel and Weinreb, like me, are of Tibetan descent but were born in the West — Chophel in France and Weinreb in New York City. When he introduced our tour to his piece, in which a spiral composed of small graphite lines implies the familiar seated form of a Buddha, Weinreb mentioned that he recited mantras while drawing each individual line, treating his artistic process as a form of meditation.

“I make abstract, meditative works that deal with the ethereal and sublime and have a pseudo-spiritual approach to them,” he said, describing his artistic style.

While some of Weinreb’s work depicts particular, culturally specific iconography — he has sculpted offering bowls and a religious text — Chophel’s does not. “My work is pretty abstract,” she said.

“There’s a couple different ways of categorizing Tibetan art,” Weinreb said. “You could be a Westerner and make thangka paintings, and that’s Tibetan art. You could be a Tibetan in Tibet, but be making nothing identifiable as Tibetan art.”

Earlier, Maki had mentioned that she was reluctant to consider “Tibetan contemporary art” to be a meaningful or useful category — outside of its value in communicating the content of an exhibition. “If we say ‘contemporary art,’ most of the museum-going audience will need something else to fix upon,” she said. “‘Well, what kind of contemporary art? What can I expect when I go in there?’”

“What is good [about the exhibition] is giving the opportunity for people to see Tibetan art that’s not exactly what they expected, what’s different from tradition — saying that actually, the diaspora has made the culture evolve, and it’s alive,” Chophel said.

How would she characterize her own art?

“I’m making abstracted spaces, landscapes, that try to offer some immersive spaces for the viewer to meditate on,” Chophel said. “Some kind of journey through the expression of natural forces and elements.”

At a panel discussion on the exhibition later that afternoon, Chophel explained her artistic process: She layers different types of paint on the canvas (oil, enamel, and marker in the case of “Inner Dialogue”) and then abrades and sands them, producing sprawling, organic-looking images. This led me to consider how the painting, at one point, had looked like something entirely different. The various treatments applied to its layers of paint had reshaped the work and could not be undone. Further alterations would only add to the mess of entropy embodied in it.

༤

Each of the plaques accompanying a Shear collection thangka share a single sentence in common: “Maker(s) not known by WCMA.” Their provenance — history of ownership, in art-world language — is unknown and, according to Maki, particularly difficult to pin down due to the 1950s invasion.

Jack Shear, who donated the collection to Vassar, Skidmore, and Williams in 2022, attended the opening celebration. Afterwards, I caught up with him and asked how he felt about the thangkas’ uncertain provenance.

“There’s this whole current idea of repatriation,” he said. “Where do they get repatriated to?”

Shear went on to explain that in the absence of any repatriation claims, let alone an identifiable rightful owner, he saw collecting Tibetan works as a way to help preserve Tibetan culture. He told me he was inspired to start doing so after seeing a show of Tibetan Buddhist art in the 1990s.

“It opened my eyes,” Shear said. “I loved everything about it.” He then chose to highlight one particular aspect present in some Tibetan art.

“I actually like that the iconography includes copulating figures,” Shear continued. “It’s symbolic and that’s what I also liked about it — that it’s wisdom and compassion being brought together.” On the tour of the exhibit, Maki had pointed out just one work depicting sexual acts.

Maki explained that not only historical differences, but legal ones, allow Tibetan works to make it into the U.S. with less scrutiny than others. Statutes require that those hoping to import art of some varieties and eras (certain dynasties of pre-modern China, for instance) produce large amounts of documentation and verification. Not so for Tibetan art.

“Some [traditional art pieces] were looted during the Chinese invasion of Tibetan cultural areas,” Maki said. “Where they assumed control, many of the monasteries were emptied out. At the same time, [the invasion] created a much larger Tibetan diaspora, some of whom carried objects with them. There are also those who remained in Tibet, and they had objects that they chose to sell or were coerced to sell … Unless there’s a real distinctive marking somewhere that tells us exactly what monastery something came from, it’s really hard to know.”

Without information that could help museums or curators do justice to previous owners of the thangkas — or even know whether or not they had been acquired and traded ethically — WCMA prioritized displaying them and sharing what was known.

A new lineage of recorded ownership had begun, though. The thangkas were referred to on the exhibit’s posters as “from the Jack Shear collection,” and on the press tour as “traditional works from Jack Shear.”

༥

As I entered the building, the two Buddhas looked down at me. Once inside the exhibit, I fell under different gazes. Six banners hung from the ceiling — a photographic work portraying contemporary Tibetan life by Nyema Droma. The twist was that they were double-sided. When I positioned myself by the hall’s entrance, they were formal portraits for which their subjects had donned traditional dress. Looking at them from the opposite side revealed the same people in their everyday clothes, some holding objects: a chef’s jacket, a cap and gown, a pride flag, a basketball.

As Maki explained, Droma was inspired by archival photographs of Tibetan subjects that had been taken on British imperial incursions into the region during the early 20th century, and displayed in the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum. The question she seemed to answer was: What happens when Tibetans, in the present day, are the ones photographically portraying each other? One could not view the exhibit’s artwork without also encountering images of present-day Tibetans — some in Tibet, others from the diaspora.

Other, non-photographic works incorporated aspects of the new homes of Tibetans in exile. Two paintings by Karma Phuntsok, who fled the invasion in the ’50s and now resides in rural Australia, portray traditional Tibetan Buddhist iconography on top of an Australian jungle and a pattern inspired by Aboriginal art.

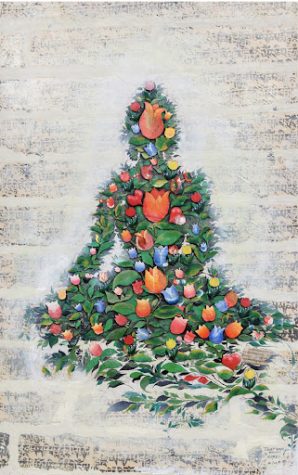

Similarly, the painting “Accepting Flowers’ Culture,” created by the Dutch-Tibetan contemporary artist Lama Tashi Norbu, depicts a Buddha made of leaves and tulips, the Netherlands’ national flower.

The juxtaposition of new works with old thangkas established that Tibetan, or Tibetan-made, art is not solely a thing of the past. It also made me think a bit differently about the latter. Weinreb’s work portrayed the adaptability of traditional iconography into a different style and medium. Chophel’s piece explored how over time, disruptions and abrasions can change the nature of an image, introducing complexity that results in an immersive “landscape.” Other contemporary artists depicted the new lifestyles and forms of expression that emerge when a group of people and their culture are faced with the irreversible distortions of invasion, occupation, and displacement.

The exhibit itself embodied this, too. A tangled web of causation had brought the thangkas out of Tibet, overseas, and into the bright confines of a college art museum. There they sat, recontextualized by contemporary artwork and new settings. Some of their history and significance had been clouded and made unknowable, consumed by a relentless creep of entropy. Wasn’t this the most familiar thing?